Alonzo King Lines Ballet at the Joyce Theater, May 5 through 10.

The dancers of the San Francisco based Alonzo King Lines Ballet may resemble us, but they look more like members of another, related species—highly evolved physically, although not always contented with their state. The eleven who perform three works by King in the company’s season at the Joyce are superbly trained ballet dancers who’ve been laboring in the mines of modern dance. The women can handle pointework, but more often dance barefooted. All are sleek and hyper-flexible—masters of complexity.

They have to be. King’s style is ornate, but not in the sense of superficial baroque flourishes. Almost no move that the dancers make (except maybe a leap or a pirouette) has one thing on its mind. Every gesture, such as reaching out an arm, takes a circuitous path; the dancer’s shoulder may initiate the movement, the head lean or turn, the ribcage respond by first pulling away and then engaging. Their spines ripple, and a single step or two may be accompanied by a veritable little flood of arm gestures—lashing, striking, twisting together, swinging. The intricacy is amazing, the intensity white hot. Like them, we have joints and stretchable muscles, but compared to theirs, ours are more like those Oz’s Tin Woodman had to lubricate regularly.

As they perform, they often seem to be looking into their bodies instead of out from them. They work those instruments like dedicated craftsmen, investigating the subtleties of their inner gears, their timing, the degree of effort involved, the flow of transitions.

King’s greatest gift seems to me to lie in the movements he designs—whether for soloists or groups. At times, he focuses more on this, I think, than in building a structure that has its own kind of overarching development. This was most obvious in one of the pieces on the program, his Concerto for Two Violins, set to the same ravishing piece of music by J.S. Bach that inspired George Balanchine’s great 1941 ballet Concerto Barocco. Sections of Bach’s work also figured in Paul Taylor’s Esplanade. King surely must have known that comparisons would be inevitable, especially in New York City Ballet’s hometown

In the assertive first movement (“vivace”), King shows off the dancers (all barefoot) in patterns that bring them together and explode them apart. He attaches two sterling male dancers (Michael Montgomery and Robb Beresford) to the voices of the two violins, but not rigidly so. And in moments of symmetry, he places Courtney Henry downstage right in the ensemble passages and Adji Cissoko downstage left; these are two magnificent women, but I confess to paying more attention to Henry at this point—not only because she’s on my side of the theater, but because she’s over six feet tall, and when she flashes those long legs, people in the front row might instinctively duck.

Alonzo King’s Concerto for Two Violins. L to R: Robb Beresford, Kara Wilkes, Laura O’Malley, and Michael Montgomery. Photo: Quinn B. Wharton

The second movement of the music, with its beautiful interweaving of the two solo violins, did not inspire King to create a duet, as it did Balanchine, or multiple canonic duets as it did Taylor. For Bach’s “largo ma non tanto,” he joins two women (Kara Wilkes and Laura O’Malley) to Montgomery and Beresford. I mean “joins” literally. The dancers appear in solos or form partnerships with the men, but these moments are very brief; most of the time, they stay close together or hold hands to form a chain and manipulate themselves within that. There are no simple moments to relieve the eye; you watch with wonder at all the intricate and unusual things that the foursome can do, until you begin to feel the weight of time. Bach has written a river, but you sense no destination in the dance. These people, you think, could just go on tangling forever. I still feel what I wrote about King ten years ago: “After watching his choreography for a while, you marvel yourself into a stupor.”

Three men and three women begin the allegro movement, and others join them to conclude the ballet. By the time Men’s Quintet, the second work on the program, gets going, you may have learned a bit about King’s preferences. For instance, he’s strong on canon and counterpoint. A group may explode into divergence, with everyone doing something different, or attacking the same phrase canonically. The image is a powerful one, reminding us that, however united a group of people may be, they do not think identically. However, I’m still pondering why King begins all three works on the program (the last is Writing Ground) with dancers lined up on the stage facing the audience—maybe forming two rows, maybe one. It’s as if he wants to say, “These are your hosts for this dance; get to know them”).

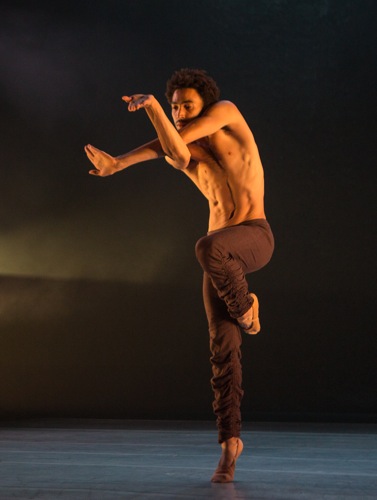

Men’s Quintet is excerpted from King’s 2008 The Radius of Convergence and set to the second movement of Edgar Meyer’s Violin Concerto (jazz saxophonist Pharoah Sanders, who played live for the original work, is also listed in the program as a composer). The five men begin in a horizontal line, advancing toward the audience and retreating from it. As individuals sink or deviate from the walking in some way, the pattern breaks up. Shortly, the men begin to show us how wonderfully each one manages the amazing physical monologues that King has devised for him. It’s no wonder that William Forsythe, a master of physical complications, wrote of King that “[H]is intimacy with Ballet’s multiple histories has made his choreography rich with the complex refractions that demonstrate a full command of the art’s intricacies. . . .”

You watch Shuaib Elhassan set his spine and limbs into fluid, unforeseen congruencies, or Jeffrey Van Sciver (or was it Babtunji?) spin a zillion times with no evident preparation. You marvel at Montgomery’s molten metal way of moving. He, Beresford, and the others have barely had time to change costumes between the first dance and this one, and are still gleaming with sweat. You can also begin to see how beautifully the five (Montgomery in particular) shape the arduous, non-stop dancing. They may suspend a movement, or hover for a second or two, before plunging into the next step.

King composed Writing Ground in 2010 for Les Ballets de Monte Carlo, and the women of Lines don pointe shoes to perform in it. This is a suite of fourteen short dances, created in collaboration with novelist Colum McCann. A text by McCann is printed in the program, and you can get a sense of the dance’s atmosphere from such lines as “There are bones that must be broken in order to be set straight” and “For the first second of falling it always feels as if you are ascending” and “She would put her bare hands into the syrup of her own body.”

Kara Wilkes, about to fall in the last section of Alonzo King’s Writing Ground. Ready to catch her: Babatunji. At right Jeffrey Van Sciver. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

In his “Thoughts on Writing Ground,” also printed in the program, King writes eloquently of movement as a language. One statement: “Whether copious or sparing, the lexicon must be clear, the alphabet legible, and symbolic meaning understood. The dancers are not just exhibiting steps or exhibiting their personality, but are actually inhabiting ideas and ciphering those ideas into communicable expression. The dancer’s personal identity is diminished in order to experience and receive information from those ideas and allow those ideas to speak.”

Writing Ground. L to R: Robb Beresford, Michael Montgomery, Kara Wilkes, Shuaib Elhassen, Jeffrey Van Sciver. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

I do not think of King’s lexicon as sparing (if I interpret his meaning correctly), but I understand his lexicon as one that explores complicated possibilities. And his statement explains the dancers’ frequent intense focus on what they are doing in order to make that as clear as possible. And I also comprehend why he has chosen many of the powerful musical selections from various religious practices—universal ideas stated differently. So a male voice sings in Arabic Jordi Savall’s “The Koran, Sura XVII 1—Mohammed Ascends into Heaven from the Temple Mount;” men’s voices intone sacred Jewish music (“Ana B’Korenyu”); the Christian “Pater Noster” rings out as a Cathar prayer; Kathleen Battle sings “Over my head I hear music in the air.”

Against a shifting backdrop that sometimes resembles gilded weaving (set and costumes by Robert Rosenwasser) and marvelously evocative lighting by Axel Morgenthaler, the dancers move in and out of a web of movement questions, assertions, insinuations, and entreaties. Now we can watch Henry and Beresford trying to stay connected, separating, and folding themselves around each other again—all to the adagio of a Geminiani concerto. Or Cissoko, eloquent in a solo set to a 12th-century French lament. Or Montgomery matching the ululations in the Arabic singing with his superbly eloquent body. Or Babtunji and Elhassen, bare-chested and antic in ruffled pants kiting around each other to the Latin Lord’s Prayer. Or Nicholas Korkos and Henry leading a section set to an Offertorium from the Codex Callixtinus. Or Madeline DeVries walking tentatively along what you might imagine as a treacherous path, having a private argument with herself, laying one hand on the floor, as if that took courage, and dragging herself away—all while Battle is pouring out her voice.

Kara Wilkes walked along by (L to R) Jeffrey Van Sciver, Shuaib Elhassan (hidden), Robb Beresford, and Michael Montgomery. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

The last section is the longest. And although it is the most wrenching, it feels too long. The accompaniment, “The Tsaok Offering,” is chanted by the deep, deep voice of Lama Gyurme. Wilkes is the heroine of this (and a dancer-heroine for performing it). Although she sees beyond the four men who attend her, watch, support, and victimize her, her body reflects the torment she is feeling. If she’s about to fall, Elhassen, Montgomery, Beresford, and Van Sciver catch her, but they also entrap or lift her—sometimes against her will. Their domination of this woman feels endless. You imagine the terrific Wilkes as an increasingly demented prisoner or as a visionary like Joan of Arc. Just before the end, she sits laughing silently while they stare down at her. There’s no emphatic ending. I think I see them beginning to toss her around again on the nearly dark stage, but that could be my imagination.

The audience roars its approval at the end of the evening, and anyone coming on another night would be able to cheer other casts. King has honed his company members (and they have honed themselves) into remarkable performers—their skin, bones, muscles, and thoughts gathered to invade and full every instant. Whatever cavils I may have about King’s choreography, I applaud the strengths he has given these remarkable dancers and the ways in which he shows them individually to us like the jewels that they are.

Wonderful review. My wife and I saw the Wednesday night performance. You so perfectly captured the tangling movements of the second half of the first Bach piece. I was in the first row and felt I could not really keep the whole thing focused. It would have been better to be seated farther back; but it was absolutely wonderful. I agree about the last piece being two long. You found the female to be laughing near the end and I felt she was showing how orthodox religion tends to restrain women, and she was driven to delirium.

I love your reviews!

Great, evocative and nuanced movement description and analysis — with illuminating photos to illustrate your points — my favorite kind of review!. . Beautiful work Deborah!