American Ballet Theatre opens its Lincoln Center season with one-act masterworks from its repertory.

When watching the classics of 19th-century and early 20th-century ballet, it’s wise not to ask too many questions. When enjoying Michel Fokine’s 1909 Les Sylphides, for instance, you’re not supposed to wonder what this lone man is doing amid all these women in long, gauzy, white tutus, two of whom are leaning fondly on him, while a couple of others kneel and gaze up at him. He’s a leftover from Chopiniana, the first version of the ballet, in which the composer, Frédéric Chopin, figured as a character. In Les Sylphides, however, he’s just there in the forest, jumping softly, as if he had sylph aspirations. Beating his legs together in cabrioles as he proceeds across the stage, towing one bourréeing sylph with him, he could be the balloon whose string she’s holding.

In a Wednesday matinee during the first week of American Ballet Theatre’s spring season at the Metropolitan Opera House, this could-be-Chopin or possible poetic misfit youth is simply a very fine dancer, Joseph Gorak, I can live with that. And he doesn’t prefer to dance with Stella Abrera because she’s so tender and sympathetic (rather than Sarah Lane, who leaps more vigorously than he’s allowed to, or Veronika Part, who is voluptuously dreamy and taller than he is). The Chopin piano pieces— mazurkas, waltzes, nocturnes—heard here in a lovely orchestration made for the company in 1941 by Benjamin Britten (lost until recently)— guided Fokine in his choreographic choices more than any ideas of forest relationships.

Les Sylphides, coached by Fokine himself, opened the first-night program of a new company named Ballet Theatre on January 11, 1940, and the company often made that a tradition. I do sometimes chafe at drawn-out tempi. In today’s performance, the orchestra, conducted by David LaMarche, honors recent custom and dancers’ wishes, but Chopin could faint between notes. I also sometimes wish Fokine’s ghost would drop in and clarify that gesture of listening, and another that could represent calling other forest spirits and/or blessing the ground in this moonlit forest with its ruined chapel (set by Alexandre Benois, lighting by Nananne Porcher). But ABT dances the fragrant, plotless evocation of Romanticism excellently, from these soloists with their airy abandon and searching gazes to the corps de ballet women who periodically re-arrange their poses and locations to frame the action, as if they were the paper lace on an old-fashioned valentine.

Another ABT Les Sylphides cast: Thomas Forster and Hee Seo, plus two corps de ballet sylphs. Photo: Gene Schiavone

Two other ABT classics were programmed for the May 13th matinée: Antony Tudor’s Jardin aux Lilas and Agnes de Mille’s Rodeo. Although the former was choreographed in 1936 for England’s Ballet Rambert and the latter for the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo in 1942, both found homes at Ballet Theatre early on—Tudor’s ballet in 1940 and De Mille’s in 1950.

Tudor’s exquisite chamber work is set the lilac-filled garden of a country house. We can see the lilacs in Peter Cazalet’s set and sense the rooms beyond the confines of the stage, where food may be served and partners continue dancing. What’s fascinating about the work is that its dramatic theme is also the overarching theme of the movement. For reasons that we never learn, none of the four protagonists who have assembled at a party to celebrate an impending wedding can be united with the one among them whom they most love. The appellations Tudor gave them reveals the problems they face: Caroline, Her Lover, The Man She Must Marry, and An Episode in His Past.

Therefore the ballet is a web of stolen moments, of quick glances to see who’s coming, of guests who must be entertained and deceived. And when the pairs of ill-fated lovers think themselves alone, they allow themselves the kind of desperate rapture that precedes being torn apart forever.

Tudor made the brilliant choice of setting Jardin aux Lilas to Ernest’s Chausson’s Poème, rather than to music intended for dancing. Written to display a violin virtuoso, Poème doesn’t offer the musician big show-off moments, difficult as the music is. The violin sighs and storms above and within the orchestra, calling out, raging, then subsiding into swooning melodies.

Over its rhythms, the choreography creates its own rhythm of rush and pause, control and abandonment. In the ABT cast that I saw, Xiomara Reyes danced Caroline and Thomas Forster her lover; Alexandre Hammoudi was Caroline’s bridegroom and Christine Shevchenko his former mistress. I wanted to see this matinée in part because Reyes is retiring after this season. I have admired her performing and how she has grown in artistry since coming from Cuba to ABT in 2001.

I found her Caroline very touching —beguilingly innocent and vulnerable. Yet she also shows mature resolve; she wants not to break down. She must marry this stiff-backed man (we can make up our own reasons), and she will do it with dignity. In this ballet, Tudor’s choreography often has the dancers keep their arms down; whether held at the sides or just hanging loosely—a device that suggests both Edwardian decorum and helplessness. That helplessness on Reyes’s part is highlighted by the fact that the two men are much taller than she is, even when she’s on pointe, shivering her feet in one of her “what shall I do now?” moments.

Another ABT cast for Jardin aux Lilas: Cory Stearns as The Lover and Hee Seo as Caroline. Photo: Marty Sohl

There was something a little off about this matinee Jardin aux Lilas, and it’s hard to pinpoint it, since all the dancers are fine ones. Perhaps Amanda McKerrow and John Gardner, who staged the ballet, were short on coaching sessions. Hammoudi plays the husband-to-be as if his spine were a ramrod and his shirt too starched; he looks not just stern, but pompous. If I think back to other performances, this one’s overall rhythms seem less urgent than I’d expect. When Shevchenko rushes toward Hammoudi and should, with luck and skill on both their parts, be able to half-turn in the air and suddenly be sitting on his shoulder, the act can have the effect of a gasp. In this case, you see the mechanics too clearly. When Reyes whips off a rapid, despairing pirouette near one of the stage’s wings, you need, I think to be startled when Forster appears unexpectedly and arrests her momentum before she finishes.

As I recall, there was some debate years ago about Hugh Stevenson’s costumes. No one ever said they were marvelous, but they emphasized the diversity within this little society and Tudor didn’t want them changed. I can see why. One woman, for instance, wore a dark green dress, similar in color to the Lover’s military jacket. She seemed to know of—or have guessed—these tangled relationships; you see another woman, whom we take to be the bride’s sister, turn to and put a warning finger to her lips. This “sister” wore a white dress, which united her with Caroline and made her interventions stand out more. There’s even the slightest hint in the choreography that the woman in green had an interest of her own in the Lover.

Cazalet has muted all the costume colors. Too, the woman who plays the possible sister (Courtney Lavine, I believe) wears a dull blue-gray dress almost identical in cut to a slightly greener one worn by another of the women (Isadora Loyola, Lauren Post, and Jennifer Whalen) who dance with the gentlemen guests (Grant DeLong, Patrick Frenette, Blaine Hoven, and Jose Sebastian).

Agnes de Mille’s cowboys against Oliver Smith’s sky in Rodeo. Second from right: Misty Copeland. Photo: Gene Schiavone

Restraint is not a characteristic you associate with Rodeo. The cowboys on Oliver Smith’s red-skied ranch of a set (with Tom Skelton’s original lighting) walk with a loose-limbed, sore-assed swagger and wheel their arms as if winding up to fling imagined lassoes. Yet de Mille was a master of drama, and Aaron Copland was willing to insert pauses into his terrific score to accommodate her ideas. As has been noted before, Rodeo can make today’s feminists wince. The tomboy cowgirl, who likes to wear pants and ride with the guys (in part because she has a yen for the Head Wrangler) will never get a man (that’s the message), until she puts on a dress and acts more like a girl should.

Still, the ballet is charmer, even if the Cowgirl does get taken for a ride a few too many times by a horse she can’t control (no horse, of course; it’s all told by her skitters and staggers as she’s bucked offstage). The little square dance without music on the forestage during a scene change was a brilliant touch on de Mille’s part (Sterling Baca calls the number while dancing in its rapid maneuvers) So was the idea of having the Champion Roper show off for the now appropriately garbed (and instantly desirable) Cowgirl with a tap dance.

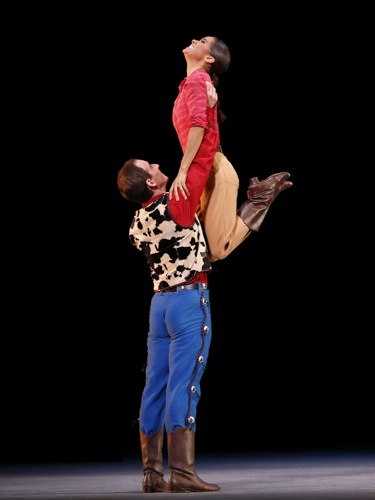

Craig Salstein as the Roper hoists Misty Copeland as the Cowgirl in de Mille’s Rodeo. Photo: Marty Sohl

Craig Salstein is better than ever as the Roper—an easy-going whiz with his taps and expert at making his small gestures and character motivations read true and clear. Roman Zhurbin is fine as the rival Wrangler, and so is Leann Underwood as the girl who has her heart set on him. Misty Copeland makes her debut as the Cowgirl this season, and she’s delightful in her alternations of toughness and downheartedness (although she overdoes the latter a bit, just as she hoists her skirt out of the way more times than are needed to show it’s an unfamiliar garment). Her elation when she finds herself in love with (and loved by) the Roper lights up the stage.

There’s one strange event in this solid staging by Paul Sutherland. At some point during the Saturday night hoedown, the Cowgirl, still in her trousers, lies in a disconsolate heap at one side of the dance floor, and no one notices her. I also count it a strange event that in this marvelously strong, vibrant, up-for-anything company, one of the cowboys looks as if he’d rather be somewhere else today.

On this program of wonderful music supporting wonderful ballets, David LaMarche conducted the orchestra for Les Sylphides and Rodeo, and Orsmby Williams led it for Jardin aux Lilas. Benjamin Bowman was the excellent violin soloist for the last.

It’s a fine thing that ABT’s artistic director, Kenneth McKenzie, has devoted the first week of the company’s eight-week Met season to “Classic ABT” programs like this before presenting an array of full-length story ballets: Othello, Giselle, Sleeping Beauty, Romeo and Juliet, Swan Lake, and Cinderella. Coming up, more splendid dancers to see in roles big and small and the last performances of three cherished ballerinas: Reyes, Julie Kent, and Paloma Herrera. In the weeks when ABT and New York City Ballet are performing across Lincoln Center Plaza from each other, dance lovers could well go crazy trying to decide which one to see when.