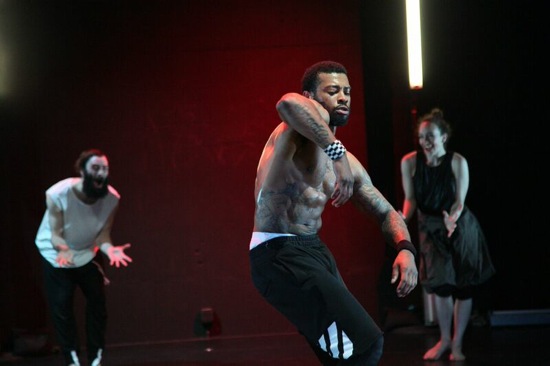

Patricia Noworol Dance Theater performs at New York Live Arts.

Troy Ogilvie and Aaron Jones, aka AJ “The Animal” Jonez, in Patricia Noworol’s Replacement Place. Photo: Aeric Merideth-Goujon

After I had seen Patricia Noworol’s ?Culture in 2013, when it was performed at St. Mark’s church, I wrote that the piece meshed “scrupulous designs with brashness, virtuosity, colloquial manners, outrage, and satiric political incorrectness.” The situation was volatile: Noworol, a violently skillful woman with a mane of blond hair, had constructed and performed in ?Culture with a group of remarkable male hip-hop dancers, and she raged about current hot topics in an accent that revealed her native Poland.

Although Noworol’s early work was made in Germany, her company is now based in New York, where she got her MFA at NYU-Tisch, and her new work, Replacement Place, which debuted at New York Live Arts, is less overtly political than ?Culture but no less raw and unconventional.

The program mentions that she casts a work in relation to its content. This gives me pause. That’s because the four performers involved make such an unlikely ensemble that you can imagine Noworol assembling people who interested her and then figuring out what to do with them. At some point, the company she formed in 2008 as Patricia Noworol Dance became Patricia Noworol Dance Theater, which gives her considerable artistic leeway.

She is not in the cast this time. But the astounding Troy Ogilvie is on hand, a dancer with a capital D (remember her from Andrea Miller’s company or from Sleep No More or other appearances?). Nick Bruder (who played Macbeth in Sleep No More) is an actor who also dances and choreographs, Aaron Jones, aka AJ “The Animal” Jonez, a co-founder of Era Dance Crew, has developed a style of flexing that he calls “Animal Animation.” The program identifies Chris Lancaster as “an electro-acoustic cellist composer.” What these four create together in Replacement Place is the performance of a ruckus with glimpses into its process, and how these people merge or don’t seems to be the binding idea behind it.

Often the performers will move so impetuously that you imagine them to be improvising; then they repeat the passage exactly. You think you know what Lancaster is about when he draws snarling, screaming, thudding sounds from his cello and twists knobs to add other elements, yet, of course, he can pick up his bow and play sweet melodies (joined, only on the night I was there by cellist Brent Arnold). After a period of time acting independently, the three dancers drop to the floor and roll in more-or-less perfect unison.

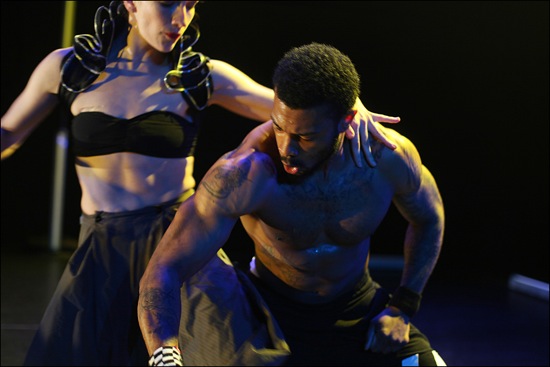

Chris Lancaster and Troy Ogilvie in Patricia Noworol’s Replacement Place. At back: Nick Bruder (in white) and Aaron Jones. Photo: Miguel Anaya

Lancaster’s instrument attests to his punishment of it; part of one side of its body is plastered with red tape. But there are no bandages on the other performers. Surprisingly. After marching across the stage several time and giving us a penetrating stare, Ogilvie launches herself into a lavish bout of dancing in which she seems to stretch and bend and pull steps askew—balancing when you’d expect her to fall, giving her virtuosity a ragged edge. Bruder stuffs his feet into high-heeled boots and grouses under his breath, before beginning to sing Radiohead’s “Creep” into a hand-held microphone, accompanied by Lancaster’s groaning cello (“You’re so fucking special/ But I ‘m a creep/ I ‘m a weirdo/ What the hell am I doing here?/ I don’t belong here”). Jones, who has rushed in earlier, knocking off insanely high straight-up jumps every few feet, is urged by Bruder to take off his shirt, which he does, revealing his powerful, pumped-up muscles. While he embarks on a brief, wrenching duet with Ogilvie, Bruder continues singing.

I should mention that the stage design by Vita Tzykun consists of fluorescent tubes arrayed vertically at the back of the stage, as well as horizontally to define the floor. Also that lighting designer Barbara Samuels sometimes makes these flash on and off and adds other effects, such illumination by red sidelights or the shock of a change to harsh white overhead lamps.

In this arena, the performers come and go and do extraordinary things. In one solo, Bruder, after undulating his spine uncannily, slants sideways and, stiff as a log, crashes to the floor (no hands). He does this twice. Jones in his solo stints displays his uncanny ability to perform and redefine the stylistic variants that comprise hip-hop, here choreographed into seamlessness. His shoulders, head, torso, feet move as if his joints were oiled and his sinews silk; face down on the floor, he moves as if he were floating an inch above it. He also takes a turn at rapping.

The interactions among the four can be casual—as if they were at a rehearsal. They signal to one another with words or gestures. Ogilvie reclines for a while, watching Lancaster play, before crawling offstage. After soloing, Bruder stretches and wiggles across the floor supine, until he’s in front of a television monitor that Lancaster has rolled out and is watchimg. There Bruder launches a fit that resembles a human version of the dancing “snow’ on the screen. He and Ogilvie watch while Jones dons a stretchy gray buttonless coat and ripples inside it, making the loose fabric fly out like moth wings; suddenly he yells and, turning, presses the other two against the back wall. The cellos scream for them.

Toward the end, Ogilvie lets down her hair, and she and Bruder dance closely together—pressed against each other spoon-fashion, wrapping, enfolding. Lancaster plays low, low chords. Bruder’s hair by then is as wild as his partner’s, and his bushy black beard adds to the image of animals mating. As punctuation, she formally bites the finger that he has extended near her mouth. However, this is no instinctual act. They separate, run to the back of the stage, and start the duet again. They begin a third time, but the lights flash and finally black out.

Watching Noworol’s Replacement Place is not like spending an hour with a bunch of personable, talented people who are unafraid of risk or intensity (although they are all these things). It’s more like being at a wild party of strangers sizing one another up, or at a zoo at night, when stray growls come out of darkness and claws scratch metal.