How do you comprehend/contend with/survive death and upheaval? A hurricane topples structures and scatters hoarded mementos; memories blow through the minds of the dying. How to control those, how to hold your world together? David Neumann, actor-dancer extraordinaire, head of David Neumann/Advanced Beginner Group, makes a piece and titles it I Understand Everything Better. The facts are these. Both his parents, Honora Fergusson and Frederick Neumann, veteran performers with the vanguard theater ensemble Mabou Mines, died in 2012—his mother suddenly, in their New Jersey house, his father gradually, months later, also at home, cared for by son David and hospice workers. Between these two cataclysms, Hurricane Sandy struck.

A vision of carefully controlled chaos awaits spectators walking into the Abrons Art Center to see I Understand Everything Better (co-commissioned by the Center and the Chocolate Factory),. At the back of the stage, a triptych of plywood panels perches on a rumpled hill of translucent plastic sheeting. Stage right sits an indescribable pileup of structures and objects—not all of them visible. Console, computer, desk, low wooden chair, bookcase, microphones, what looks like an aquarium but isn’t (?); behind these, a small drum set and a bass guitar. That’s not all. Most of us can’t see the coffee pot that later will be plugged in and produce coffee (the process recorded and projected onto the plywood panels). Dangerously long blue and orange wires snake along the floor or tangle into nests. Toward stage left, at some distance from these: a lamp mounted on a slender, knobby branch. The vertically sliding metal door at the back of the stage is partly open. It looks as if the contents of a room are awaiting the moving company, but all of this has been designed by Mimi Lien. In the big open space remaining, the performance swims and staggers and ceremoniously strides into existence.

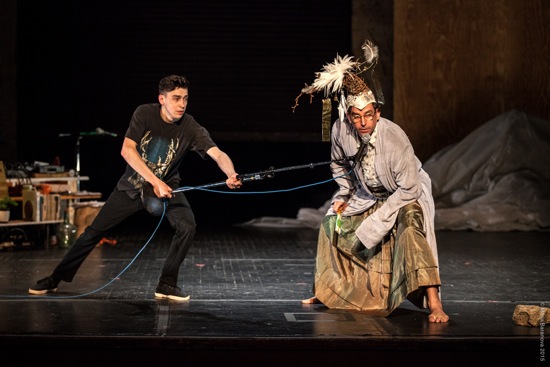

The stylistic control dreamed up Neumann and Sybil Kempson (who wrote the script with his input) alludes to Japanese Noh and Kabuki theater—not so far out considering Neumann’s parentage. In Noh drama, terrible catastrophes occur, distanced by being recounted as memories and laid to rest. The principal actor (shite) is arrayed in transformative costumes onstage by black-clad stagehands. I Understand Everything Better remodels these conventions, along with the comedy provided by the kyogen plays that traditionally alternate with Noh dramas on programs.

The first action is a brief, spare, walking dance performed by Neumann, Tei Blow, John Gasper, and Jennifer Kidwell. They walk, stop, hunch over and twist to look back or lean to look up. The storm that is to come, the death that awaits. They stay in a cluster but change directions—now walking on a diagonal path, now in a circle, back to back, now facing each other. They lift a leg, reach an arm. Call it a ceremonious prologue. Now these four are ready to play their assigned roles (which include being themselves).

Blow is the sound designer, actor, and occasional drummer; also, as with the waki (or second actor) in Noh, his remarks can provide background. The equally versatile Gasper and Kidwell manage props and help with costume changes, in addition to portraying the bored, worried, or tired hospice workers (like the tsure in Noh, who is usually a companion of the waki or the shite). They also man a camera and a microphone for the television newscasts—shooting Neumann against a portable green screen (with the projection showing him before a weather map) or onsite in the storm-lashed city). At times, they address us in synchrony, like members of a chorus. It is they who warn us, “We will now walk the thin line between the purely presentational and the deeply personal.”

Neumann, displaying his immense gifts as an actor and a dancer, channels brilliantly—and sometimes hilariously—his dying father; the meteorologist reporting on the storm; and another dying father, Shakespeare’s King Lear. These and more are layered, alternated, or butt-jointed together in intricate ways. At times, we hear him as a voiceover. After the opening sequence, he reappears in the first of several eclectic costumes: a shabby bathrobe worn over something full that we can’t yet make out and a fantastic hat that takes off from Noh and Kabuki headdresses and also somehow links up with the birds (French ones, we’re told) that we occasionally hear— and once see in a projected image. Advancing toward the front of the stage, he lifts one leg and drops into a position with his feet planted wide apart. It’s a mie —the swaggering Kabuki actor’s sequence-ending pose—performed with fierce precision and settled into with a taut little shake. Following this, he’s helped into the low-to-the-ground chair and asked if he slept well.

This episode points toward the kind of shifts that follow, and introduces elements that are repeated as the principal actor slides in and out of Frederick Neumann’s memories and fantasies. There was a party in the hospital that he liked, and when he got tired, his bed was right there. Gasper and Kidwell tell him that he’s in his own house now, a house he built. Periodically they remind him of this. Several times he suggests an outing; it’s a nice day. Will they join him? Politely they accept, and all walk along together. There’s mention of a road trip. One of the “outings” that the four performers take together, is an elegantly arranged sequence of steps that—travelling back as often as they go forward—lead nowhere in terms of stage space. (This strategy is reminiscent of the way a Noh actor may take a few steps across the stage and announce that he has already arrived at his miles-away destination.)

Although the underlying journey that Neumann has created has an end, like Lear’s, it also obliquely suggests those of characters in certain of the Samuel Beckett plays that Mabou Mines has presented who never reach a destination.

It’s difficult to convey just how complex I Understand Everything Better is. For example, the soundscape is rich in associations. We hear the hurricane bluster and the sound of feet splashing through water. We hear those birds. Either Gasper or Kidwell strikes boards together to provide the accentuating “CLACK” that is heard in Kabuki performance. Once, when Neumann is offstage, there’s a tremendous clatter, as of stuff falling out of closet crammed with pans, and we hear him cursing. Blow contributes sound effects and taped music of all kinds, including sweet violins and what sounds like a rinky-dink song from kiddy tv. He plays the drums while Gasper handles the bass guitar (they’re all but out of sight behind the furniture that the principal actor keeps being puzzled about).

In theatrical terms, the confusions, the associations, the approaching storm, and the daily business of caring for the principal character wax and wane. The rhythms falter, then zoom vividly forward. The highly theatrical drops into the mundane. Comedy breaks the tension of tragedy.

The piece is wonderfully imaginative in its handling of the themes and sub-themes. As the storm ratchets up (greatly helped by Chloë Brown’s lighting), Neumann-as-newscaster leans into the wind provided by a standing fan, holding a microphone attached to such a long blue cord that you imagine he could fly, kite-like, into the eye of the hurricane; the others scatter papers, which blow in the wind.

As the storm reaches its peak, and I Understand Everything Better nears its end, Neumann, wearing a billowy, light-weight “kimono” made of translucent fabric, stands atop the “hill” in flickering lights and disastrous crashes to cry out, with terrific force, Lear’s defiance in the face of another storm: “Blow winds, and crack your cheeks! rage! blow!” Between Shakespeare’s lines, Neumann interjects cries of fear and amazement (“What the. . .?”). Rushing on and off the stage, he looks as if he too is being wind-whipped. But he can also turn until the garment furls around him, as constricting as the kimono worn by actors playing female roles in Japanese theater.

As the storm subsides, the principal character’s sense of what’s inside his mind and what’s present drift even more gauzily around together. His confusion is expressed through Japanese gibberish, the newscasts, the hospital party, the sounds of feet sloshing through water, Timothy Leary’s words on altered consciousness (read by Blow). There’s a fleeting reference to The Tale of Genji. Storm, risen waters, and journeys lead to an imaginary boat, which Neumann rows with convincing effort, talking as he goes (says Blow-Leary, “The person may perform repetitive and restless tasks”). Sitting in the little chair, wafting a fan, Neumann asks Kidwell to turn him in various directions, which she, with difficulty does; finally she says, “Fred. Are you fuckin’ with me?” and he, very softly and amusedly, replies: “Yeah, I think I’m fuckin’ with you.” Lying supine, his headdress removed, he reports to the listening public that the ceiling is falling in.

When Neumann is dancing his beautiful final dance—striking poses and wielding his fan—the birds sing, then fall silent. Dancing with his arms winging, his body bending, his feet stepping, while the light brightens. In contrast to this quiet exaltation, this preparation for a journey, Gasper gets ready to go off duty, and Kidwell say, “I’m here until he’s gone.” And Neumann. Just. Exits.

Thank you, a lovely review, I wish I could’ve seen the work too!

Lovely review of a wonderful work. Interesting that you reference the Mabou Mines Beckett plays as it reminded me that David Neumann performed with Baryshnikov in some Beckett shorts as well, so those characters are known to him through both his parents’ and his own performance.