Martha Graham’s Dark Meadow and Merce Cunningham’s Biped are performed by Juilliard students.

Every Spring, Juilliard’s dance students pass through a compelling ordeal and emerge as artists just beginning to come into full bloom. The ordeal is really an awakening. A work by a major choreographer is auditioned for, learned, rehearsed, and performed. The dancers come to understand how great dancemakers shape their works, how they construct a world.

Each year, Lawrence Rhodes, the artistic director of Juilliard Dances Repertory, chooses pieces that will both suit and challenge the students. For 2015, he selected only two long ones: Martha Graham’s Dark Meadow (1946) and Merce Cunningham’s Biped (1999). That dancers enrolled in the Juilliard School have classes in both Graham’s technique and Cunningham’s means that the first hurdle has been crossed already. But understanding the qualities and fine points that characterize a style or grasping the aspects of a character are more difficult tasks, and these the Juilliard students attack with marvelous skill and intelligence. Faculty member Terese Capucilli, who has performed, with distinction, the leading character in Dark Meadow, staged and directed the work, with coaching assistance from Christine Dakin (who has also danced that role) and Elizabeth Auclair, another former member of the Martha Graham Company. Jennifer Goggans and Jean Freebury, both of whom graced the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, staged Biped.

Graham said on several occasions that she had no idea exactly what Dark Meadow meant while she was creating it, and understood it, if at all, decades later. The Juilliard program note reproduces her original one, in which she speaks of “the adventure of seeking” and provides four poetic clues:

“Remembrance of the ancestral footsteps—

Terror of loss—

Ceaselessness of love—

Recurring ecstasy of the flowering branch”

When Graham made Dark Meadow, she was pondering the archetypes of which Carl Jung wrote, as well as taking notes on Frances Cornford’s From Religion to Philosophy: A Study in the Origins of Western Speculation. Cornford, writing of the Greek philosopher Empedocles, says: “The Soul is conceived as falling from the region of light into the ‘roofed-in cave,’ the ‘dark meadow of Ate’”—. (It is not insignificant that during the year that Graham was choreographing Dark Meadow, she and her lover, Erick Hawkins were enduring a period of separation, even though he was teaching in her school and performing in the dance).

In creating a role for herself, One Who Seeks, Graham turned the stage into a pristine jungle of symbols. Four sensuously smooth grayish sculptures by Isamu Noguchi stud the space like dolmens from a vanished temple—two clearly phallic; one a sharper, taller, more pointed pillar; one a slanted resting place when it’s not standing upright. Among these and on them move the heroine in her long red dress (Tiare Keeno in the cast I saw); He Who Summons (Jeffery Duffy); She of the Ground (Kellie Drobnick), whose long, narrow, knitted gown gives her the look of an Etruscan statue; and They Who Dance Together (Angela Falk, Gemma Freitas, Zoë McNeil, Amber Pickens, Emily Tate, Evan Fisk, Austin Goodwin, Alex Larson, and Riley O’Flynn).

They Who Dance Together in Martha Graham’s Dark Meadow. (L to R): Zoë McNeil, Riley O’Flynn, Amber Pickens, Brian “Alex” Larson, Gemma Freitas, Evan Fisk, Emily Tate, Austin Goodwin. Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

To a score by Carlos Chavez for an excellent ensemble of Juilliard musicians playing four wind instruments and four stringed ones, and in lighting created by Beverly Emmons in 1998 after Jean Rosenthal’s original designs, the dancers enact a kind of transformative ritual, for the most part using the music only as atmosphere. When they jump sturdily from foot to foot, or rise onto the toes and let their heels thud back to the floor, their heard rhythms give an urgency to Chavez’s composition. Angling their arms and cupping their hands at their sides, the women smack their hips. Once, when Duffy is dancing with assertive athleticism, Keeno, standing almost motionless, thumps her feet rhythmically on the small platform where she stands. Some of Graham’s finest choreography is for the men and women of the ensemble. When they dance in pairs, the positions they assemble themselves into could be viewed as erotic, except that they are distanced from any overt expression of that. They fit themselves together like two pieces of an interlocking puzzle. At one point, several of the men walk ceremoniously along, each carrying a bundled-up woman in his arms, as if she were an offering.

To me, the mysteriousness of Dark Meadow is part of its beauty. When women enter and “plant” various symbolic objects in holes in the small platform, the central man and woman, crouching down, confront each other across it, as if it presented a board game to be solved, or issues to be argued over. Various props convey the woman’s journey in search of. . .what? Love, surely, and Spring, and fecundity. She travels along a dark trail of fabric, gathering it up, pulling it along, wrapping herself in it, and emerging seated, with the cloth covering her head as if it were a Mexican woman’s shawl. Finally, She of the Ground takes it and exits, tossing it repeatedly into the air, as if a shroud had become as harmless as a toy. She’s also the one who brings in a bowl of crimson cloth that the seeker dips her hands into briefly, and the one who swathes the most phallic of the objects in a filmy green cloak before spinning away.

Kellie Drobnick (L) as She of the Ground and Tiare Keeno as One Who Seeks in Martha Graham’s Dark Meadow. Photo: Rosalie O’Connor

The season slowly turns in these most austere ways. A sculpture reveals its white side; another becomes red. The heroine slowly and gravely pulls a dark cloth covering one phallic structure down the length of that dolmen (a startled giggle erupted in a spectator near me); a cruciform shape, with a dagger-like gout of red hanging at either end of its cross-arm is “planted” atop another. In the end, the principal male, who has often observed the action, half hidden behind one of the structures, pulls a concealed wire, and a branch of green leaves “grows” out horizontally, the way old-fashioned stop or go signals used to lever into position.

The dancing Graham created is firm, clear, and strong. The summoner dances with vigor and power; no indecisions or conflicts for him. The seeker, on the other hand, is often twisting in indecision, caving in—her body contracting as if the breath had been knocked out of her—crawling, and launching herself into big, tipped-over turns. When the two dance as a couple, they may fit together, spoon fashion, but their other conjunctions imply tension and struggle. He grasps her waist and crawls in her wake.

This dance is an enormous challenge for today’s young dancers. The combination of fierce energy with precision and controlled drama is unlike much of the dancing they see today. Every one of them rises to the challenge beautifully. Duffy is wonderful at modeling large-scale dancing with a directness of focus that only enhances his image as a man of power. Keeno has a more difficult task. She cannot possibly know or show all that Graham, fifty-two years old in 1946, dredged out of her soul. But she gives a dedicated and wonderfully expressive performance.

It tickles me to see Cunningham’s Biped share a program with Dark Meadow—in part because Cunningham was still dancing in Graham’s company (although taking on no new roles) while she was gestating that piece. Two years before its premiere, he had presented his first solo program, with music by his partner, composer John Cage, and was alreadys making dances that told no stories, let alone ones that tackled sex, jealousy, and death.

Cunningham turned 80 the year the marvelous Biped premiered, but retrospective visions were not in his line. He was, instead, fascinated by technological developments. Paul Kaiser and Shelley Eshkar created the piece’s visual design using the technique of Motion Capture, collaborating with Cunningham, the dancers, and lighting designer Aaron Copp to create a world that would reveal itself in ways that the choreographer likened to “flicking through channels on TV.”

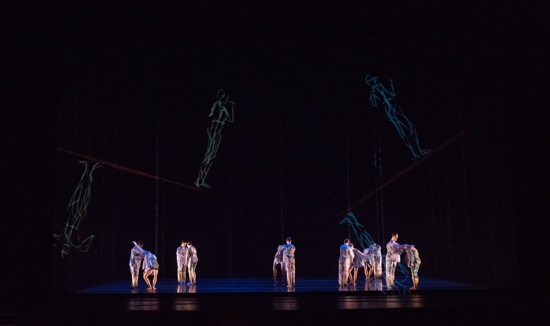

The score by Gavin Bryars for violin, cello, guitar, double bass, and keyboard (excellently played by Juilliard musicians) drives its own intriguing course through a shifting space. Various of the seventeen dancers enter not only from the sides of the stage but through invisible gaps in the backdrop—suddenly there, materializing out of darkness. The floor they dance on is unpredictable too; rectangles light up here and there on its surface, then disappear—a digital board for an unknown game. Moving projections appear on both the rear surface and a front scrim: horizontal or vertical bars of light, diagonal streaks, orderly columns of small bubbles, washes of color, and more. Most astonishing are the intermittent fleeting appearances of motion-captured dancers. Some of these are giant figures suggested by Eshkar’s slashes of chalk; others, somersaulting past, are limned in white dots; at one point, a small, almost realistic mannikin dances for a few seconds high up at one side.

The dancers themselves flicker. Suzanne Gallo’s shiny, multi-colored costumes bring to mind the mother-of-pearl linings of abalone shells; later, filmy jackets soften their outlines. These are, indeed, beautiful bipeds—erect and busy-footed, with long, probing legs. They flash into the air in their jumps and leaps, but they also pause or draw certain movements out. The choreography is extremely demanding in terms of coordinating dissident torsos with legs with arms, and its rhythms are equally challenging. I caught a few minutes of Jennifer Goggans talking about this on a monitor set up in the lobby. She demonstrates a certain hop in which the free leg moves from a position with its foot touching the ankle of the standing leg, stretches out when the dancer is in the air, and is back at its original place on the landing. But, wait, that’s not the rhythm Cunningham wanted; the leg must both flash out and return to place while the dancer is still in the air. At another moment, a dancer busy with her own sailing steps or swings of a leg or tricky interactions of feet with floor may land near one who is slowly, smoothly rotating on one leg, the other lifted behind him; suddenly, without warning the traveler’s pattern merges with his, and both of them are revolving, their legs like lazy fan blades. And remember this: the music, travelling its parallel path doesn’t guide these maneuvers.

In Dark Meadow, only some of the characters enter and leave the stage. In Biped, they’re appearing and disappearing all the time, giving the impression that their terrain extends beyond the confines of the stage. We see soloists, pairs, threesomes, scatterings of five join together or co-exist in their own individual tasks. Six may join in unison. Encounters crop up, develop, and dissolve. Occasionally a dancer seems for a second to stick to another in passing. They pay no attention to the projected “dancers” who loom above them or fly by, benign visitors from another world.

The terrific Juilliard dancers enter Cunningham’s world primed for whatever happens and—with all their senses alert to the moment—celebrating it.