The Liz Gerring Dance Company brings her Glacier to the Joyce Theater.

Liz Gerring graciously titles her Glacier after the piece of music by Michael J. Schumacher to which it’s set. His score for guitar, piano, harp, cello, clarinet also contains recordings he made near Glacier Lake in Colorado, and it is these sounds that are prominent during the beginning of the dance: a rattle of little stones, a tumbling of larger ones, lapping waves, soft humming sounds and squeaky ones, rhythmic thuds. They continue, too—sometimes quietly, something at assaultive volume—when instruments play. Snatches of the Allegretto from Beethoven’s 7th Symphony stalk under a faint aural miasma.

It might be misguided to link Gerring’s wonderful dance too closely to glaciers. Nevertheless, her palette is—at least at first—bracingly cool and crisp. The dancers, with the exception of Tony Neidenbach, wear simple, individualized costumes of white, black, and gray; Neidenbach’s t-shirt is sky blue. Robert Wierzel’s design consists of a white floor and three huge, pale rectangles hung on the black rear wall of the Joyce Theater’s stage. His lighting palette is clear.

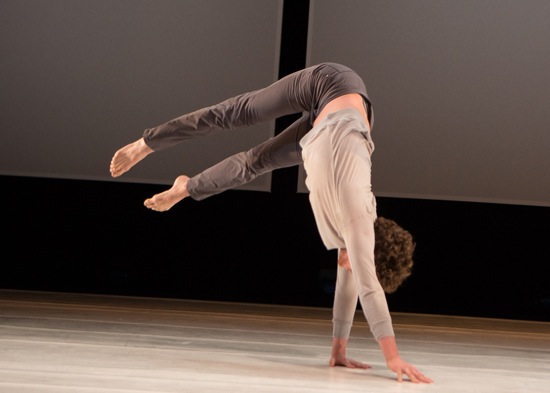

In addition, Gerring’s way of structuring makes me think of ice floes breaking apart, shifting, coming together in new congruences, drifting away. Claire Westby and Brandin Steffensen begin with what turns out to be a theme. (Movements from it or sections of it will appear throughout the piece, and very near the end, the theme is reintroduced and shifted into a canon and (almost) a fugue.) The two dancers execute the movements calmly and deliberately—whether they are hunkering down to place their hands on an unseen flat surface, bending forward and letting their arms hang down, leaning back to open their chests to the sky, swinging their arms into a new direction, dropping into a deep lunge, or performing any of the other maneuvers involved. The simple movements contrast elegantly with one another in terms of shape, directions in space, and the performers’ gaze.

Starting close together and in immaculate unison, Westby and Steffensen have ended up on opposite sides of the stage, still in unison, when Adele Nickel enters, lifts one leg like a pointer, and begins to pace between them. Her coming—attended by what sounds like a large rockslide— introduces a pattern that will persist. Throughout the hour-long piece, the eight performers migrate onto the stage and off again; sometimes they stay for a while, sometimes only for second. There may be three or four at any one time, or a single person, or all of them. They may enter with a relaxed walk, a rush, or a plunge. They give the impression of leaving when they wish. Once, Nickel exits by means of a chain of rapid little turning leaps (like ballet’s sauts au basque) and almost immediately re-enters. Once, she and Westby, holding both each other’s hands, jump their way off the stage, turning as they go.

Gerring introduces her very individual dancers gradually. Brandon Collwes is the fourth to enter. Then Jake Szczypek steps in and assumes the initial pose of the evening. After a while, Jessica Weiss makes an appearance. Some minutes later, while Steffensen is circling his torso around—almost, but not quite pulling himself off balance—Benjamin Asriel enters. Often a newcomer introduces something not previously seen; for Asriel, it’s hand gestures that vaguely resemble ladder climbing. When Neidenbach comes into view, the piece is so far along that his advent is a big surprise. So is his first contribution. He runs in a large circle, slows it down to a walk, runs some more, walks. Soon he’s reeling.

There are many such surprises, some of them witty. Steffensen grasps Nickel’s hands and swings/spins her off her feet. Westby and Weiss exit on hands and feet. Steffensen comes in and picks Nickel and almost immediately puts her down; she exits. Asriel holds a balance for an uncommonly long time, tilted forward with one leg lifted behind him. Late in the game, several of them jump clunkily from foot to foot, their legs wide apart and bent. The men form a line across the front of the stage, hold their arms out to the sides, and present themselves more or less as a fence.

The texture thickens. The movements become a little more turbulent and larger in scale (how deep can a lunge go before it turns into something else?). The pace picks up, then relapses, then increases. The music can become threatening or agitated. It’s fascinating to see how the choreography can lead you to believe that dancers’ paths will intersect or unison dancing result; sometimes neither happens. At other times, the dancing seems infectious—or magnetic— drawing a newcomer in. Six performers pair up and work together, as if investigating possible strategies. Yet all eight of these people have individual agendas, and their focus on these is almost unwavering. You come to know them and to admire the way Gerring has accommodated their personal styles, even as they strive to make her language theirs.

What you first accept as beautifully designed and arranged movement structures, with the dancers as diligent engineers shifting the elements of a composition to give you new perspectives, you come to see as pursuits that engage and test some marvelously skilled human beings and lead them in new directions. These pursuits don’t end. The light brightens. A few people are still trying things as darkness falls.