Paul Taylor’s American Modern Dance Lincoln Center season invites other companies to share programs with Taylor’s works.

Member of Shen Wei Dance Arts performing Shen’s Rite of Spring on Paul Taylor’s American Modern Dance season. (L to R): Sara Procopio, Russell Stuart Lilie, Kate Jewett, Jessica Harris, Cynthia Koppe, Michael Wright, Jordan Isadore. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

Beginning in the late 1920s, American choreographers, especially those pioneering what came to be called modern dance, built companies around themselves that featured their own works only. In the past decade and this one, we have seen a variety of ways in which choreographers plan their legacy (or fail to do so wisely). The Alvin Ailey American Dance Company had become something of a repertory company before Ailey’s death. The groups founded by José Limón and Martha Graham eventually found that in order to survive they had to recruit or commission works that didn’t clash with their deceased leaders’ styles. Merce Cunningham wished his company to disband after a final two-year tour, but his dances are available to other carefully selected companies.

Paul Taylor is thinking ahead. During his company’s just-ending three-week season at Lincoln Center, he has begun to introduce—to test— a plan for its future, while he is still its leader, and to announce the future implementation of that plan. On several programs, his own dances shared the bill with either Shen Wei’s 2003 Rite of Spring (performed by Shen Wei Dance Arts) or Doris Humphrey’s 1938 Passacaglia and Fugue in C Minor (performed by members of the José Limón Dance Company, an inheritor of Humphrey’s legacy and that of her partner Charles Weidman). Shen’s work opened four of the season’s twenty programs, and Humphrey’s appeared on three.

The next step: Doug Elkins, Larry Keigwin, and Lila York will each be given a six-week residency to create a work for the Paul Taylor Dance Company in its new incarnation as part of Paul Taylor’s American Modern Dance.

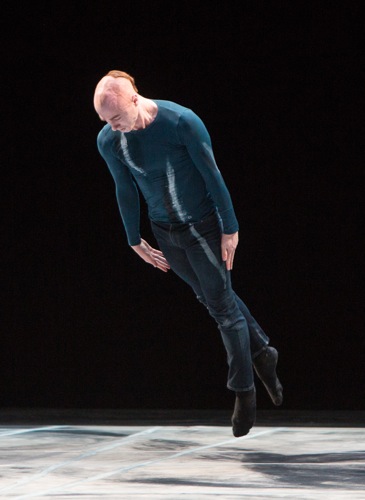

Shen Wei’s Rite of Spring. (L to R): Jordan Isadore, Cynthia Koppe, and Sara Procopio. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

Shen is a dance polymath. He is credited with the concept, choreography, costumes, set, and makeup for his intense response to Igor Stravinsky’s monumental Sacre du Printemps. The choreographer chose to set his Rite of Spring to the four-handed piano version of the score. It was published the same year that both Vaslav Nijinsky’s ballet and the composer’s orchestral thunder shocked Parisians attending the premiere by Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. Interestingly, the four hands accompanying Shen’s ballet all belong to the same pianist, Fazil Say, who overdubbed the two parts and apparently also manipulated certain effects. Believe me when I tell you that the power of that recorded masterwork shook the theater.

The choreographer made it clear in a program note that he is telling no tale of virgin sacrifice, only creating structures suggested to him by the music’s atmosphere. In his dance, the almost forty-minute score’s occasional silences before a wallop of sound portend no savagery to come, but simply accompany calm pauses, while the dancers absorb what has happened and prepare for what follows. When Kate Jewett dances alone, you might be tempted to see her as a heroine, but sooner or later, almost every dancer will swim into prominence, while still being part of a community that rarely separates its inhabitants by gender.

While the house lights are still on, the dancers walk onto the stage in silence, one by one and take up places facing different directions. All wear trim, similarly designed black and dark-hued outfits (except for Alex Speedie, who is in blue), and their faces are without conventional makeup. The gray floor they move over is sparingly and asymmetrically streaked with what resemble chalk lines—some parallel, some forming diagonals. It takes quite a while for all sixteen performers to enter. Eventually, the stage, lit by David Ferri, suggests an unknown board game, with all its “men” waiting for dice to be thrown. Then, the house lights dim, and Stravinsky’s sweet opening melody sounds out.

For a while, the dancers move very little; your eye catches this one turning to face a new direction, another taking a few skittery steps on tiptoe. Movement impulses, like random gusts of wind, stir them. An individual may start something, and it gradually becomes infectious; pretty soon, everyone is doing it. And, of course, the music will not let them alone. Before long, they are flinging out one arm, swirling to the floor, recovering their equilibrium through a back somersault, and falling again.

They come and go, forming patterns and dissolving them. Sometimes individuals’ straight or curving paths are so contained—especially when they travel by means of rapid, almost robotic little steps that don’t affect their arms or heads or bodies—that you might think them in a maze. At other times, a dancer or two races across the stage. They slip out of their own patterns and into those of others; it’s a surprise to find all of them seated. An entire line of people appears at the side of the stage so quietly that you’re almost shocked to see them.

In fragmentary ways, the scenario buried in the music pokes its head out of the choreography. At the musical passage when the Chosen Maiden of the original ballet (and many subsequent ones) stands quaking, dancers advance toward the front of the stage and stand there; minimal twitches and shivers invade their bodies. At one point, Jewett drags herself along, or you see, at the back of the stage, behind everyone else, a woman (perhaps it is she) falling over and over. Because Speedie wears blue, you’re tempted to think of him as a priest or leader whenever he appears.

The absence of narrative doesn’t keep Shen’s engrossing Rite from feeling like a ritual. The strenuous, splendidly performed dancing—with many movements and phrases recurring many times—suggests a communal ordeal. You want it to keep going. You want it to change. You want it to stop. Which is it? You don’t know. Near the very end, there’s a stunning moment when twelve people dancing in four lines of three suddenly explode into being different from one another. It’s like a last carouse, since the stage soon darkens around a central, glowing pool of light. Which could be Spring.

Members of the José Limón Dance Company in Doris Humphrey’s Passacaglia and Fugue in C Minor. Standing center: Kristen Foote; seated center: Durrell R. Comedy. Photo: Melanie Futorian

Doris Humphrey choreographed her Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor during the summer of 1938, when she and her company co-director, Charles Weidman, were teaching at the Bennington School of the Dance and rehearsing works to be performed at fifth Bennington Festival. There, Humphrey could augment the Humphrey-Weidman company with apprentices, but although twenty men and women performed in the work at its premiere, she designed it so that cast size could be adjusted. The revival, staged by Jennifer Scanlon and shown during Paul Taylor’s American Modern Dance season, featured all sixteen members of the José Limón Company.

Taylor danced in Doris Humphrey’s 1935 New Dance in 1952, when he was a student in her repertory class at the American Dance Festival, and Humphrey (who died in 1958) was coaching the piece. Maybe he remembered how uplifting her works could be. I recall Passacaglia from a 1965 revival that I had hoped to be in myself when it was part of American Dance Theatre, a short-lived attempt to bring major modern-dance figures into a repertory situation. When I saw the chosen dancers, led by the marvelous Lola Huth and Chester Wolenski, I found that work and Bach’s tremendous music also to be uplifting.

If one picks certain descriptive words out of an account of Passacaglia by one of the 1938 apprentice dancers, here’s what you get: “vigorous, dynamic, exultant climax, strong down beat, ecstasy, lyricism, vigor, and excitement.” And while the Limón dancers’ performed this beautiful piece of spiritual architecture with dedication and professional skill, you could never apply all those words to their presentation. The stateliness that is intrinsic to this musical masterpiece, in part because of the ostinato that repeats its deep-voiced melody underneath all that ensues, is part of the choreography too. Yet at the heart of Humphrey’s guiding theory of Fall and Recovery is a sense of the body’s weight, which often involves an the interplay between suspending a movement and acknowledging gravity in its descent. Until the Fugue rolled out its rich counterpoint, the dancers seemed, at the performance I saw, to be dancing on the music’s surface much of the time. And that music, although played by the master organist Kent Tritle didn’t come across with the power and volume that he could have delivered on a major instrument.

The José Limón Dance Company in Doris Humphrey’s Passacaglia and Fugue in C Minor. At right, leg raised: Ryoko Kudo. Photo: Melanie Futorian

Passacaglia and Fugue in C Minor plays with three-dimensionality in fascinating ways. The three-tiered pyramid of platforms—on and in front of which the dancers are standing in silhouette when the curtain opens—raises the choreography into vertical space (lighting by Brandon Stirling Baker after Humphrey’s concepts). It and the small platforms beside act almost like magnets—symbols of order that draw the dancers back to them after their forays into asymmetrical adventures. When the dancers on the platform raise both their bent forearms in front of their breasts like fence rails and, over and over, wrench them to the side and back to the center, you feel a rocking that could destabilize this society. Equilibrium and harmony seem to be sought. Dancers step out and bow forward, lifting one leg behind them; on the next step they raise their other leg to the front, look up, and bend slightly back. Sometimes, when the group breaks into segments, the stage picture remains symmetrical, as when two women pair up on either side of the center line. Yet there are other possibilities in this society; once, a woman stands by herself on one of the side platforms and lifts one leg high, while balancing herself with a hand on a nearby dancer’s shoulder—a single beacon emerging in an unexpected place.

Kristen Foote and Durrell R. Comedy lead the group in the roles once taken by Humphrey and Weidman. By lead, I don’t mean anything military. They seem to be venturing along possible paths and testing the terrain with big, sweeping movements, soft leaps, and turns. Sometimes they draw the others into unison. When everyone, standing on one leg, joins in repeatedly swinging the other leg, sending each of them into half-turns, you think of bells tolling together in rapturous harmony.

In Humphrey’s hands, counterpoint becomes a vision of blocks of people wrestling their ideals/motions into new alignments and reconsidering the old ones. While Passacaglia begins with all the dancers facing the back of the stage, their dark group outline against a glowing sky, it ends with almost all the dancers divided into two symmetrical groupings; in the avenue between them, the two leaders face the empty platforms and the possible vision beyond them. For Humphrey in 1938, Utopia was worth attempting, even as events in Europe were trampling down the values she stressed in a program note: “for love, tolerance, and nobility.”

In a sense, Taylor’s own beautiful Promethean Fire also danced to music by J.S. Bach (his Toccata and Fugue in D minor and Prelude in E-flat major, as orchestrated by Leopold Stokowski) also exalts the ability of people to move together. It too is performed by an ensemble of fourteen dancers, led by a man and a woman (James Samson and Parisa Khobdeh). It too stresses formations and tableaux. However dancers in this 2002 work of Taylor’s swoop across the space, into the wings, and back into view, whereas Humphrey’s never leave the stage.

And they don’t just swoop; they leap, they crash to the floor and roll. Prometheus restored fire to humankind, stealing it from where Zeus had hidden it in revenge for some trespass. The Taylor dancers, in their black and gold oufits by Santo Loquasto, strike sparks with the movements themselves—sometimes men alone, sometimes women, sometimes couples. They’re fiercely energetic, but not always joyful. In the slow, beautiful duet for Sansom and Khobdeh, they can be tender, yet at one moment, she’s on the floor, clutching his ankle as he drags her along. Seconds later, they’re apart, and she races across the stage floor and, from an alarming distance, leaps into his arms. In this section, Jennifer Tipton’s superb lighting hints at fire.

An earlier cast in Paul Taylor’s Troilus and Cressida (reduced). Jamie Rae Walker as Cressida. Three Cupids (L to R): Kristi Tonga, Eran Bugge, and Heather McGinley. Photo: Paul B. Goode

On the two programs I attended in order to see the “guest” works, Taylor showed his enjoyment of farce and his darker, kinkier one, along with large-scale major works like Promethean Fire and Beloved Renegade. The program note for his 2006 Troilus and Cressida (reduced) is “O Cupid, Cupid, Cupid!” The line is spoken by Helen of Troy in Shakespeare’s play of that name. Taylor makes the image a literal one; Jamie Rae Walker, Aileen Roehl, and Heather McGinley—all with blonde wigs— are mischievously helpful Cupid triplets. They have to promote the romance between an apparently narcoleptic Cressida (Khobdeh) and a shy dope of a Troilus (Robert Kleinendorst), whose green velvet trousers (Loquasto again) are apt to fall down. Samson, Michael Apuzzo, and Michael Novak as Greek invaders add to the misadventures, the pratfalls, and the confusions.

Diggity (1978), set to a terrifically playful score by Donald York (who also conducted the Orchestra of St. Luke’s), is a light-hearted, somewhat mysterious romp (why is Heather McGinley wearing only silky underwear?) in what I imagine as a grassy spot. The stage is populated by Alex Katz’s painted cardboard cut-outs of dogs (multiples of the same two) in various positions. Among these obstacles, eight dancers play happy games, occasionally resting in positions rather like those of the canines. Eran Bugge, leaping around, is as boisterously happy as a little girl let loose on the first day of spring. She seems to be the one to set things in motion.

There’s a cheerful duet for Roehl and Francisco Graciano and another for Michelle Fleet and Kleinendorst. In both, the participants seem friendly, rather than romantic—mirror-imaging each other and leaving alone. A cutout of a giant cabbage materializes and becomes a screen to disappear behind; on the reverse, it’s a sunflower. The five women, including Laura Halzack, are buoyant. The men (including George Smallwood) squat down and jump like frogs. Remember Perry Como singing “Hot Diggity Dog” in 1956? Cute and silly. Guess it got into Taylor’s head and eventually had to come out.

An earlier cast in Paul Taylor’s Big Bertha. (L to R): Amy Young as Big Bertha, Michael Trusnovec as Mr. B., and Eran Bugge as Miss B. Photo: Paul B. Goode

On one of the programs I saw, Passacaglia was followed by Taylor’s Big Bertha (1970). Gulp. Re-set the brain. This little horror show features a gaudily elaborate antique band machine that “plays” recorded tunes from the St. Louis Melody Museum’s collection, along with special effects by John Herbert McDowell. “Bertha,” the life-sized automaton, who conducts jerkily and occasionally swallows her baton, is a horrific vision, here played by Christina Lynch Markham, is a lustful nemesis who reduces visiting families to blood-spattered, half-clad victims. By the time she has finished wielding the baton like a magic wand, “Mr B.” (Sean Mahoney), a cheerful paterfamilias in a Hawaian shirt, has become a demented and horny maniac. His initially puzzled and horrified wife (Fleet) has taken off her circular felt skirt (set and costumes by Alec Sutherland) and is standing on a chair whipping the skirt and her hips around. The perky little daughter (Bugge) has been hauled by her dad behind the machine, and when she emerges, what clothes she still has on are blood-stained. “Bertha” has her eye on “Mr. B.” A girl can get lonely all by herself on a band machine. The discarded skirt becomes his cape, his movements get jerkier and jerkier, and he ends up as her new automated partner.

All the performers are excellent, although Lynch Markham doesn’t yet have the deadly precision with gestures that Bettie de Jong exhibited at Big Bertha’s premiere. Sean Mahoney is especially superb as the disintegrating family man lurching into depravity. What was going through choreographer’s mind when he create this nasty little masterpiece is anyone’s guess.

Whatever Paul Taylor has to do to insure the continuation of the splendid repertory of dances that he has created is fine by me. And let us hope for more works—great and small—from him for years to come.

I saw you at the performance of Passacaglia – Big Bertha – Troilus & Cressida – Beloved Renegade. I wondered what you would think of Big Bertha. I was speechless at the end. I knew it was carefully crafted, but I couldn’t figure out why it was crafted, and still don’t.. I couldn’t bring myself to applaud.

I suppose I expect Taylor to probe the dark side occasionally. He seems to like to remind us that sweet-as-apple-pie families may have dirty secrets. You feel like washing your mind out after seeing Big Bertha.