Douglas Dunn + Dancers premiere Aidos at BAM Fisher.

Doulas Dunn’s Aidos. Jules Bakshi, surrounded by (L to R of those visible): Timothy Ward, Alexandra Berger, Emily Pope-Blackman, and Jin Ju Song-Begin. Photo: Christopher Duggan

Aidos seems to have been a goddess slightly confused about her own identity. No wonder she is said to be the last of the Greek gods to leave earth after the Golden Age. The Random House Dictionary of the English Language calls her “the personification of conscience,” but she is also seen as representing shame and modesty. I see a connection to Australia’s “tall poppy syndrome,” in which it’s ill-bred to vaunt yourself as better than others, and others like to cut down those who do so.

I’m only bothering about this, because Aidos is the title of a beautiful dance that its choreographer, Douglas Dunn, has no reason to be ashamed of, although shame often figures in dancers’ training and careers. The goddess, anyway, is a fair-minded and conscientious one, as opposed to her companion, Nemesis, who is all for vengeance when she sniffs evil-doing.

It is perhaps the Aidos-Nemesis polarity that led Dunn to create so many symmetrically balanced designs in this new dance. But first, the enigmatic prologue that is going on when quite a few audience members are still shivering into BAM Fisher from the very cold streets. An immense, translucent white sheet covers some lumps in the performing arena, which is surrounded by seats on three sides. When eight of the nine dancers enter, dressed in white coveralls, and begin lifting and turning the fabric and settling it down again, Jules Bakshi is intermittently visible beneath it, rolling over and around two big, brown, padded objects (designed by Andrew Jordan) that roll on their own. As the handlers travel around the space, they have to keep kicking the things back under the fabric. Eventually, they make it billow like a parachute, and finally, Bakshi is on top of it, like a mermaid being loved by waves and eventually buried under them.

L to R: Jules Bakshi, Alexandra Berger, Emily Pope-Blackman, and Jake Szczypek in Douglas Dunn’s Aidos. Above them, cellist Ha-Yang Kim. Photo: Christopher Duggan

I think of the birth of Venus, but that might not be relevant. Although another kind of birth happens once the latecomers are settled. Up in the balcony, Ha-Yang Kim begins to play a sarabande, the first of the twelve pieces drawn from J.S. Bach’s six Suites for Cello that will accompany Aidos. The music resonates impressively in the cavernous black space that is gradually—barely—revealed by Carol Mullins’s expert lighting. The dancers are on the floor, waking up to something. They all know the same small vocabulary of moves and run through them slowly, each in his or her chosen order (lie down and stretch legs up, sit with legs straight in front, kneel and put both hands on the floor, lie prone, limbs akimbo—things like that).

Then the place brightens and symmetry is introduced by Alexandra Berger and Emily Pope-Blackman. As they dance in unison, they stay opposite each other and at some distance. The movement is leggy, the women’s feet active; a few times they make skirmishing gestures with their hands, but they also run, hop, turn, prance, and wiggle their hips subtly. Dunn is a master at giving all body parts an opportunity to be discreetly busy—not necessarily at the same time.

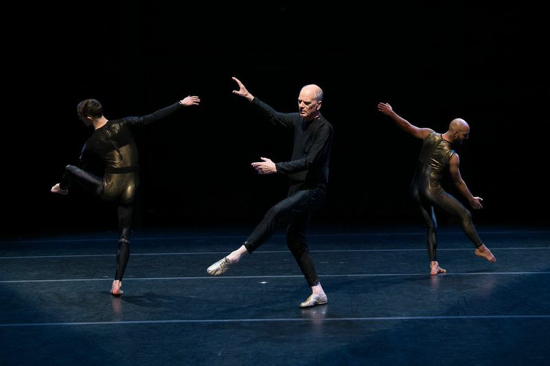

The women are attired in extraordinary costumes by Jordan. These are form-fitting patchworks of shiny black fabric and even shinier gold material, each outfit patterned differently. Under the lights, the dancers sometimes resemble warriors in strange armor or in carapaces like unholy beetles. Kim strikes up another sarabande, and three men—Paul Singh, Timothy Ward, and Dunn himself—replace the women. They wear similar costumes (although Dunn’s is topped by a more loosely cut shirt, and he has gold shoes). Their dancing defines a circle; although they don’t necessarily travel in one, they make you aware of the space they enclose, and it’s almost a shock when they start criss-crossing it.

(L to R): Timothy Ward, Douglas Dunn (not in costume), and Paul Singh in Dunn’s Aidos. Photo: Christopher Duggan

Similar allusions to equilibrium occur in a strenuous, quick-footed quartet for Pope-Blackman, Berger, Jules Bakshi, and Jake Szczypek. The dancing is wonderful to watch—a village celebration elevated to an Olympian rite—and equally interesting in a playful male-female duet by Ward and Bakshi and a subsequent dance for three couples (male-male, female-female, male-female).

The equilibrium of this little world begins to change. Awkwardness enters with cautious, tottery steps that still maintain a trace of grandeur. Two men swing Pope-Blackman, and the remaining three performers arrive in time to catch them as their effort disintegrates. The women crouch on the men’s backs and ride them. They promenade dreamily in pairs, staring upward this way and that. They creep in squirrely ways. What can be happening?

Dunn re-enters with Jessica Martineau and Jin Ju Song-Begin—two tall women costumed in unitards patterned in pinks and oranges. He walks them, drags them around, while the others rest and watch. Meet Aidos and Nemesis? The two stand back to back, joined at the hips and slide one after another foot out (walking but going nowhere), while the others rouse themselves to encircle them and wheel one arm around and around, as if urging them on, or winding them up.

I lose track of what occurs, but quite a lot does before the dancers separate and exit, the theater goes dark, and Kim—aloft in her spotlight—tunes her cello. Three pairs dance again; so does Dunn. He confessed in an interview with Gia Kourlas for Time Out, to being ashamed of being ashamed of dancing at his age (he is in his seventies, spry, quick of foot, a bit stiff, and a riveting performer). After he soloes, the three men scuttle around him and lift him in various ways. He remains hopeful.

Jessica Martineau (L) and Jin Ju Song Begin in Douglas Dunn’s Aidos (dress rehearsal). Photo: Christopher Duggan

Now comes a bigger change. Two chairs are set side by side at the back of the space. Their backs are shaped to indicate femaleness—beige heads without faces and busts. Enter the dual aspects of the goddesshood under scrutiny. Queens for sure. Dressed now in black and white, trailing long capes. Song-Begin’s crown is a wreath of up-pointing icicles; Martineau’s is made of equally agitated twigs. The capes and crowns they place on the chair-women and sit to watch and preside, smiling tolerantly and picking at invisible bits of stuff on their clothing. Everyone is up for a ritual.

Suddenly (or was it gradually?), formal statements about music and dancing and give-and-take yield to a battle. Song-Begin and Martineau confront each other in dance, embodying both the grandly gracious and the bestial, each with her attendants swinging with her. The symmetry approaches ink-blot clarity, but what happens is anything but clear. Squabbling and snarling silently, the goddesses are subdued and laid out, but only temporarily. Whew! No one will be allowed to escape this mad dance. Pope-Blackman hangs onto Song-Begin and Backshi grapples with Martineau. The last thing I wrote in my program before Kim stopped her bow, and Bach’s courante fell silent is, “I’ll bite you!”

Earnest fun! Thanks!