The Martha Graham Dance Company brings new and old works to the Joyce.

Abdiel Jacobsen and Ying Xin of the Martha Graham Dance Company in Andonis Foniadakis’s Echo. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

I only recently realized that Martha Graham must have been choreographing her evening-length Clytemnestra and Embattled Garden at more or less the same time. Both premiered during her company’s 1958 season. Perhaps she needed a respite from the marital quarrels, passions, and jealousies that precipitated the Trojan War. Embattled Garden, on view during the Martha Graham Dance Company’s February season at the Joyce, condenses those urges, transports them to the Garden of Eden, and mixes them together in ways that state—occasionally with a touch of wit—just how confused one can get when infuriated or in love. Or both.

You can see the four characters as the program asks you to: Eve, Adam, Lilith (some say, Adam’s first wife), and The Stranger. This last can also be thought of as the biblical Serpent, since he begins part way up Isamu Noguchi’s vividly colored abstraction of a tree. The other, equally brilliant set piece suggests a reed-surrounded pond, but also one of those once-fashionable “conversation pits” in living rooms. Lilith (Carrie Ellmore-Tallitsch in the cast I saw), fans herself and urges The Stranger (Lloyd Knight) into battle with Adam (Abdiel Jacobsen). Eve (PeiJu Chien-Pott) sobs silently a bit theatrically. Adam likes stroking Eve’s long, long black hair, but before Eve needs to dance a solo, Lilith turns The Stranger into a hair salon chair, bends her rival back over him, and ties her hair into a ponytail. At some point, Eve slaps Adam twice.

Noguchi’s hot colors and a suddenly red backdrop (lighting by Beverly Emmons after Jean Rosenthal), plus the pungent orchestral score by Spanish composer Carlos Surinach emphasize the performers’ occasional flamenco hauteur and touches such as the comb in Lilith’s hair and her red fan. There’s temporary fever running riot in this little cocktail party of world, where these people (bold dancers all) express themselves in big, strong movements and seem to forget whom they came with, whom they love and whom they don’t. Nothing, luckily, leads to war.

Liz Gerring’s Lamentation Variation. (L to R): Natasha M. Diamond-Walker, Charlotte Landreau, Ying Xin, and Tadej Brdnik. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

I saw two of the company’s three programs. The works ranged from reconstructions of Graham austere works from the 1930s, dance theater pieces dating from the 1940s, commissioned dances by other choreographers, and additions to an imaginative ongoing series devised by the company’s artistic director, Janet Eilber: very short variations by divers people on Graham’s 1930 Lamentation—the solo in which she sits on a bench, shrouded in fabric that stretches in response to her anguished gestures.

Two of the new Lamentation Variations were attached to each other and to Bulareyaung Pagarlava’s 2009 one, which ends with several men slinging a woman upside down. Tap dance innovator Michelle Dorrance designed a simple elegiac piece for a cast of ten in dark clothes, whose austere walking and shifting directions suggest the numbness that often attends a death. No tapping, but you can hear the feet on the floor. At the end, Lloyd Mayor falls, and everyone else freezes. Liz Gerring’s variation, performed by Natasha M. Diamond-Walker, Landreau, Ying Xin, and Tadej Brdnik went by so swiftly that I could hardly take it in; it seems to convey the feelings of instability that attend mourning.

Noguchi’s set for Graham’s tremendous 1947 Errand into the Maze and its costumes have been restored following the damage wrought by Hurricane Sandy. Graham made this duet for herself as a heroine seeking to confront her fears, personified by a man with a horned headdress and with a gigantic bone across his shoulders; these and his stiff movements make him appear terrifying while impeding his force. I saw both Blakeley White-McGuire with Jacobsen and Chien-Pott with Ben Schultz. The man’s role is that of a figment, a totem, a creature without emotion, whose intention is to dominate, and both men did well with the role (despite an unfortunate makeup detail that makes the Creature of Fear—that is, the mythic Minotaur—seem to be flashing a white-toothed grin). White-McGuire is a powerful performer, steely in her resolve, even as she reveals herself to be vulnerable. I was moved by her simplicity at the end, when she can untie the white cord with which she has lashed herself in with her enemy, sink down to sit in the V-shaped entrance, and take a tired breath. I believed more in Chien-Pott’s terror, but both performed wonderfully.

There were other excellent performances in Graham classics. A notable one was rendered by Diamond-Walker as the woman of the Couple in White (with Schultz) in the beautiful Diversion of Angels. I’ve always thought that woman—in a partnership designated as the most mature—to be performing in moonlight—serene, yet watchful, with stars to contemplate and a strong lover to support her. XiaoChuan Xie is well-suited to the quicksilver woman of the Couple in Yellow (with Knight). She has a dawn brightness and a butterfly fleetness, rushing to perch on his shoulder and get a better view of the world. I was less taken with Ying Xin (paired with Mayor). The Couple in Red seems to represent two people in the high noon of their relationship—sensual, ecstatic. But Xin, I think, overdoes the voluptuous happiness and makes it seem too much like the flirty joy of the woman in yellow.

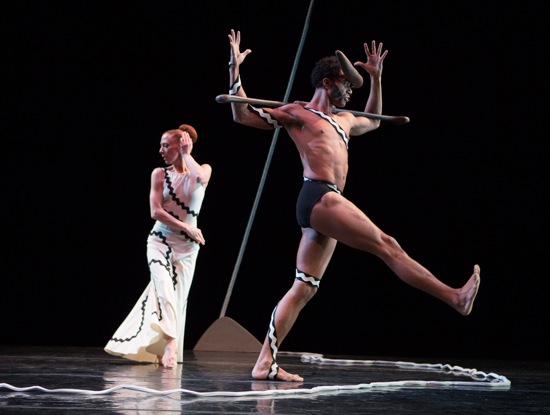

I had not seen Andonis Foniadakis’s 2014 Echo before. It’s suitable for a guest choreographer wishing to fit something new into Graham’s magisterial repertory to consider a mythical subject. He chose the tale of Echo and Narcissus, as told in Ovid’s Metamorphosis, but disrupts the narrative flow. Narcissus, who preferred hunting to dallying with women, saw his reflection in a pool and fell in love with it. But Foniadakis could not very well keep Mayor (Narcissus) and Knight (the reflection) dancing always in mirror-image symmetry, so they seem also to quarrel and to fall in love as if they were the separate individuals that they are. One of the choreographer’s most felicitous ideas was to have Brdnik, and Xie (as I recall), dressed in black, at times literally echo Chien-Pott’s gestures. As Echo (a role she shared with Ying Xin), she was punished by Juno, who took away her power of speech; she can only repeat what others say. So when she makes a move, it travels down the line of the three in black. But that could become gimmicky if it happened often; used wisely, as it is here, it’s arresting.

Echo, set to a score by Julien Tarride, becomes something of a muddle. Diamond-Walker, Schultz, Jacobsen, and Xin are in it too, and, in the watery flow that Foniadakis creates, there could well be more Echos and more Narcissuses. That quality is magnified by the fact that the men wear long full skirts of a lightweight material, so every move has an afterflow that enlarges it in space and softens the dynamics of the encounters. Watching, you can get lost in all that undifferentiated swirling.

Annie-B Parson’s The Snow Falls in Winter. Foreground: Natasha M. Diamond Walker holds Carrie Elmore-Tallitsch; at back: Tadej Brdnik teaches XiaoChuan Xie a lesson. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

In asking Annie-B Parson of Big Dance Theater to choreograph a work for the Graham company, Eilber must have been thinking of Parson’s ability to deconstruct a narrative. That, after all, was a skill that Graham all but pioneered. As artistic director, Eilber may also have been thinking of contrast—a work with contemporary resonance and a light touch that would enhance the repertory but not be completely out of place, as was Pagarlava’s sporty 2010 romp, Chasing.

Parson used Eugène Ionesco’s one-act The Lesson as a jumping-off place. And jumped far from the nasty story of a teacher who—with a housekeeper to abet him— systematically murders pupil after pupil, after taking each girl through an absurd lesson that leaves her increasingly week and confused. No crime occurs in Parson’s The Snow Falls in the Winter. But she reveals a great deal about teaching and about the slipperiness of language. The piece calls for skills hitherto in the Graham repertory. Diamond-Walker and Ellmore-Talitsch, clad in subtly irregular attire spell each other at a small table and elsewhere, talking into the microphones that get passed around. As the professor, Brdnik also speaks (and dances and puts on and takes off a hat and acts as a stage manager in moving props into the right hands.

The music (by David Lang) features Robert Black on bass, but it is manipulated, played backward, and interrupted by a voice slowed down to a distant, echoey growl. Xie plays the eager pupil charmingly, and Lauren Newman is terrific as the taciturn maid, who, in the end, literally lets down her hair. There’s a mysterious package that Diamond-Walker attempts to balance on her raised thigh and that someone else sits on. A bell rings. The performers move furniture about and perform various actions, including dancing, with crisp assurance and considerable speed—qualities that make the absurdist text and the shifting relationships all the wittier.

A handsome, swirling black-and-white projection by Peter Arnell opens each program. He has taken numerous photographs of company dancers in action and then made them appear to be moving—this to illustrate the season’s cryptic title “Shape&Design.” Interestingly, I think a similar process was used to revive Graham’s 1937 solo Deep Song, a response to the Spanish Civil War. The dance was lost, but the tormented positions captured in Barbara Morgan’s photos could be linked together. The resulting reconstruction looks striking and Ellmore-Tallitsch performs it excellently, but I can’t help thinking that Graham herself would have shaped the flow of moves to look less like a list and more like a song.

Among the pleasures of the season is the use of about forty students from fifteen New York area high schools in the version of Panorama that former Graham dancer Yuriko reconstructed in 1992 from a black and white film of (I believe) the first part. Graham made the dance in 1935 at the Bennington Festival—her chance to experiment with an augmented company. It’s something to see that many scrupulously rehearsed, dedicated young women in long, plain red dresses moving swiftly about the Joyce stage in squadrons and parades and circles to stirring music by Louis Horst.

Lloyd Knight and opening night guest artist, ABT’s Misty Copeland, in At Summer’s Full, a rendition of elements from Graham’s Letter to the World. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

I have, in recent years, been distressed by Eilber’s editing of certain Graham dances. Cutting minutes out of a masterwork like the 1943 Deaths and Entrances seemed ill-advised at best. Nor did I care for a pared down Clytemnestra that necessitated super-titles so the audience could follow the story. Now elements of another Graham classic, the 1940 Letter to the World have been extrapolated and given a new title, At Summer’s Full, that’s drawn from a poem by Emily Dickinson, the heroine of Letter. It may be that the set for Graham’s classic Letter to the World has not yet been fully repaired, or it may be that the work requires a bigger stage than the Joyce (although I doubt that).

In any case, this is a relatively harmless kind of manipulation. It doesn’t present the original work in altered form; it only leaves me thinking longingly of Letter to the World and hoping that a proper revival of it will be forthcoming. I wouldn’t like to think of this pleasant, mostly lighthearted arrangement by Eilber of some of Letter’s steps and images becoming a substitute for that superb dance.

The little white garden bench is onstage, and Hunter Johnson’s music is playing, but all the dancers are costumed in simple gray outfits with long full skirts for the women (provided by Body Wrappers). Four couples dance as if at a ball, the women swirling in their partners’ arms. They rush on and offstage, crisscrossing.

Blakeley White-McGuire channels Martha Graham in a movement from Letter to the World. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

Individuals emerge. And hints of characters. Xie and White-McGuire team up occasionally like girlfriends sharing confidences as they go, and bringing to mind Graham’s splitting of the character of Dickinson into She Who Dances and She Who Speaks in Letter. Jacobsen has a solo, perhaps he represents The Lover, or (when he jumps) March (the role once danced by Merce Cunningham). In any case, this is a civilized, largely happy gathering, and it’s a shock when White-McGuire dances angrily, alone in her frustration.

The dancers perform with dedication, power, and eloquence. Does the spirit of Graham walk abroad? If so, she would surely be proud of almost every one of them. Would she approve of the new works, the transformations, the editing? That’s harder to say.

It’s such a pleasure reading a review by someone who has a real memory of the Graham works. I just want to tell you that The Snow Falls in Winter was not commissioned by the Graham company. It was first done in 2008 as a commission from Other Shore, the company that was started by Brandi Norton and Sonja Kostich.