The 43rd annual Dance on Camera Festival at Lincoln Center.

The coats, the hats, the scarves, the shawls, the gloves, the bag, the boots. You needed them for the long, cold walk along West 65th Street in late January and early February. And then, when you got to the Walter Reade Theater, where most of the screenings in the 2015 Dance on Camera Festival took place, you had to shed these items bit by bit and figure out which you could sit on, which you could drape over your seat back and which stow under it.

Now, do you feel your snake-nature emerging from its skins into warmth? Actually, you sort of do. The five-day Festival, co-presented by the Dance Films Association and the Film Society of Lincoln Center, fosters a gemütlich atmosphere, enticing film and dance experts and buffs with showings, panels, and exhibits. Warmer climes appear—large and vividly colored—onscreen. And, inevitably, there’s not only ambitious experimental cinema to brighten the day, but also real-life tales that try to avoid sour notes while detailing triumphant struggles. How many documentaries have we seen in which the choreographer or dancer or administrator being filmed has gotten up on the wrong side of the bed and is playing Termagant for a Day? Can you name even one?

Reality shows have spread their influence. Emotions running high are a plus. So is suspense: who will win, and who will lose. American Cheerleader by James Pellerito and David Barba follows two high school varsity cheerleading teams as they train for the National Competition The Burlington Township High School team has already won two Nationals in its division and is aiming for a third victory. The twelve girls from Somerset High School in Kentucky have placed lower in a Regional competition. Pellerito and Barba switch back and forth between the two teams as they ace the Regionals and then move on to the National.

Cheerleading has become an exacting sport, not just half-time décor. The filmmakers show us the determination and grit of these twenty-four, small, lithe, strong girls. Over and over, one of them balances on one leg and holds another high while being held aloft by three others who grasp her ankle and, with perfect timing, toss her slightly and spin her into another pose. The final tableau looks like a tiered wedding cake.

Chronicling this fierce, competitive field, Pellerino and Barba managed to make themselves unobtrusive during the extensive shooting period in these two different communities with common ambitions (the members of the Somerset team all appear to be Causcasian; the Burlington team is a racially mixed one). Watching the film drops viewers not knowledgeable about cheerleading into another world of rules, goals, and athletically demanding choreography. mature in their work ethic, but vulnerable in their adolescence, the girls are prodded not just to perform their difficult tasks, but to project delight: they’re entertainers! Somerset, the underdog, wins the National (by fractions of points); Burlington places second, but, we’re later told, returns to win another year.

We hear the thoughts of proud parents, coaches, judges, the girls themselves. At 89 minutes, American Cheerleader feels a little long, but suspense holds it together. A Burlington team member participates in the Regional with a high fever, gets much sicker and has to be replaced when the group moves ahead to the National. A cheerleader has lost her mother recently. A coach’s marriage has broken up because she spends so much time coaching. Will the freshman who keeps losing her balance in rehearsal pull herself together? Over the course of the film, the team members cry, in victory as in loss; the coaches cry; the judges cry; we cry.

I saw four additional—and quite diverse— documentaries on view during Dance on Camera: Meredith Monk’s Girlchild Diary (a Festival premiere), Mia: A Dancer’s Journey (2013), Jirí Kylián: Forgotten Memories, and Dancing Is Living: Benjamin Millepied (2014).

Meredith Monk’s 1973 Education of the Girlchild, Part II. Front row (L to R): Sybille Hayn, Coco Pekelis, Lee Nagrin. Back row (L to R): Blondell Cummings, Lanny Harrison, Monica Moseley, Meredith Monk.

Monk’s film takes anyone who saw and loved her solo Education of the Girlchild (1972) and her group work Education of the Girlchild, Part II (1973) on a memory trip, and, indeed, that’s what this film is, in part, for her and those who performed it back then and in its 1993 revival (two, Lee Nagrin and Monica Moseley, have since, alas, died). Monk has made some extraordinary films, but the documentary format is, I believe, new for her. She had an editor, but no director, and even while lapping up the footage she chose to show and what it revealed about her remarkable processes and her artistic integrity, I came to believe a director’s outside eye would have been useful, especially for those viewers unfamiliar with her early music theater works.

The scenes show this composer-musician-choreographer-dancer and her gifted colleagues gathering to rehearse the projected revival in her downtown loft, or to reminisce near her small house in Meredith, New York. Monk talks wisely, and black-and-white footage from the 1970s and color footage from the 1990s and beyond dissect the magical two-part work, letting us appreciate the individuality of each performer and how a uniquely profound artist approaches the creative act.

Some documentaries add to the body of dance history, however personal the viewpoint. Mia: A Dancer’s Journey is a tribute to the ballerina Mia Slavenska (1916-2002) by her daughter, Maria Ramas, and Kate Johnson—an act of love involving considerable research and travel. The film casts Slavenska as one on the verge of being forgotten and tells her story fervently. Ramas has snapshots to show the talented little Croatian girl who gave a solo recital at the age of twelve, danced with the Zagreb Ballet, and became intrigued by modern dance in Vienna. A savvy manager helped her to a more ambitious career. Of those few interviewees who knew Slavenska, Malcolm McCormick fits her history into the turmoil of Europe between the wars (she won a dance prize at the 1936 Berlin Olympics), while the late Frederic Franklin, with his sly wit, recalls Slavenska when he partnered her in the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo and in the Slavenska-Franklin Ballet (which also featured Alexandra Danilova).

The ballerina comes across as a trouper, but rarely satisfied (Franklin agreed with her that the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo didn’t give her enough good roles). She was both a beauty and a powerhouse. Many of the film clips celebrate her ability to stand on one pointe in such perfect equilibrium that she looks as if she might decide to stay there overnight. The most powerful evidence of her dramatic ability comes in footage of the 1952 work that Valerie Bettis based on Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire (premiered by the Slavenska-Franklin Ballet). Distraught and heated, Slavenska grapples with an unusually fierce, bare-chested, tousle-headed Franklin. In her later years, Slavenska was a much-valued New York City ballet teacher. We see her in a 1990s interview, still glamorous, able to look back on her career with humor and little bitterness. And the film images, competently stitched together, end in a kind of victory. Slavenska is finally honored in Zagreb. A ceremonial funeral procession advances through the streets. She becomes a legend to countrymen and women who had never heard of her.

The ingredients of a dance documentary are almost always the same: rehearsal shots, archival film clips of performances, family photographs, talking heads, interviews with the subject, footage that indicates a time and a place. Timed and spaced, these create their own dance. When the documentary’s subject is still living, his/her taste and style influence many of the directorial choices.

Don Kent and Christian Dumais Lvowski created Jirí Kylián: Forgoten Memories, but the film is really an autobiographical collage of the choreographer’s life and career. Kylián, now in his sixties, controls it, and its tone is as calm as his voice. He walks through cities and sits in various sunlit places to talk of his life and work. Photos don’t appear magically onscreen, identified by text or voiceover. Kylián sifts through a heap of snapshots and holds various ones up for the camera to slide closer to (here’s the skinny adolescent gymnastic, grinning in a 180º split).

In contrast to his visually arresting, occasionally violent choreography, his manner with dancers is courteous and his voice soft. Rehearsing the companies he has directed in the Hague (Netherlands Dance Theatre I, II, and III) and others elsewhere for whom he has created choreography. He peppers his directions with metaphors and similes (to a male dancer: “I like here the sense of confusion—almost like you’re being attacked by your own hands”).

Documentary footage—sliced and montaged to convey the unrest and all-too-brief euphoria of the Prague Spring before the Russian tanks rolled in to suppress it—colors Kylián’s recollections of his studies and performing days in London and Stuttgart. But it is his own voice—rueful, nostalgic, stoic, contented—that tells of his travels, his jobs, and his relationships. The clips from his dances stand out from his spoken memories like flashing jewels on a calm hand.

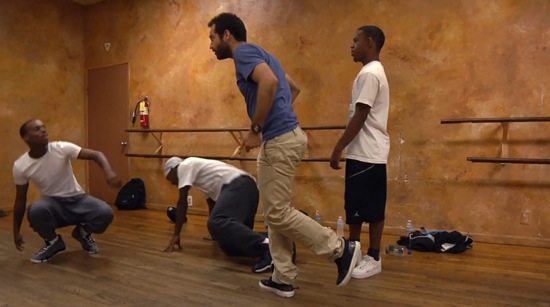

Benjamin Millepied (blue shirt) rehearses Lil Buck and two other hip-hop dancers for a Los Angeles project in Dancing is Living: Benjamin Millepied.

The tone and rhythms of Louis Wallecan’s Dancing is Living: Benjamin Millepied are very different from the film about Kylián. It’s hard to tell to what degree the nature of this choreographer’s career dictated Wallecan’s choices, and what the director’s own preferences shaped. I’m assuming that much of the 2014 film was made before late October, when Millepied took on the demanding job of directing the Paris Opera Ballet, while working closely with the L.A. Dance Project, a small company he established in 2012 and in whose affairs he is still active. So, although the film shows little of his negotiations in Paris, but a lot about all the other projects he pursues and the traveling he does, many of Millepied’s explanations of what moves him and what he values in dance, etc. are couched in French, with English subtitles (although at moments, these inexplicably vanish).

I imagine the camera panting as it pursues Millepied—pausing at a respectful distance or swinging around to catch a move on the fly while he devises maneuvers for the Los Angeles company, dogging him as he walks down a long corridor to revisit the purlieus that nurtured him as a student in the School of American Ballet and groomed him to be a Principal Dancer in the New York City Ballet (where he’s now an occasional guest choreographer). Wallecan likes extreme facial closeups; once, while perusing Millepied’s eyes and mouth, he suddenly pulls back to include his subject entire head, neck, and shoulders, as if thinking better of such artful intimacy. Shots of landscape attempt to tell us where Millepied is now in his whirlwind life, (although no helpful typeface identifies these). At one point, the film cuts away from him working out duet maneuvers with L.A. Project dancer Amanda Wells and gives us a glimpse of a barren landscape and what could be a distant roadhouse, then returns to the studio scene. Was that supposed to be a reminder of where we are? You have to smile a little when Millepied speaks about how important transitions are in choreography; Wallecan could take this to heart.

Millepied’s private life is not discussed, although his parentage and his childhood in Africa are touched on. In terms of his choreography, more process than product is shown, although we clearly see his wide-ranging interests: a quartet of men in checkered shirts dancing a work he made for the Lyon Opera Ballet; members of the Mariinsky Ballet preparing for another Millepied piece; Lil Buck and two hip-hop colleagues conferring with him about a Los Angeles project (not entirely clear to me what) and trying out moves with them to Bach; Millepied working on a simple routine with the little students of the Gabriela Charter School and talking warmly with them and the school principal about dance. Scenes in these locales recur times, echoing the juggling act that is this choreographer’s career.

The Paris Opera Ballet, with its bureaucracy, hierarchies, and multitudes of employees with are culturally miles away from Millepied’s own ensemble of eight superb performers who are not primarily ballet dancers (one sequence shows rehearsal director and knockout dancer Charlie Hodges running through a juicy solo). Millepied views the whole venture as a collective (composer Nico Muhly is one member of it). The dancers—creative and independent—speak insightfully of what the group is trying to achieve and what it means to them. In 1994, as we see in the film, the spindly SAB student had already been singled out by Jerome Robbins for his high-level dance intelligence. This film’s implicit suspense hangs in the air while the credits roll. Will this guy be able to maintain what could be a daunting high-wire act? No is evidently not an option.

Of the over fifty films shown at Dance on Camera, twelve were shorts—the two longest clocking in at 13 minutes, most less than 8. It’s always fascinating to see what an independent filmmaker comes up with in terms of an idea and an approach. In her 7-minute Embrace, Shantala Pépe of Belgium and the UK sets a man and a woman on a bench on a grassy cliff overlooking the ocean; the light is misty and lovely, and the bench becomes a slippery place on which on which to condense the intricacies of their relationship. In Escualo‘s 4 hot minutes, the lanky, gutsy identical Lombard twins, Martin and Facundo (U.S.A.), are captured tapping fiercely and competitively in an empty window-lit studio. It only takes 2 minutes for Geoffrey Goldberg to establish what he expects to become a series about a tap “stalker.” In his witty A Tap Dance on the Pier, stationary camera work with no cuts presents two men, a bench, and a pier, one man reading a newspaper. One starts tapping, the other, in a suit and tie, surreptitiously and tentatively joins; before long they’re in expert unison and moving around the bench (oddly, the tapper rarely acknowledges the stalker who has become his partner-for-a-day). An empty, sharply angled street corner in Montreal becomes the site and the raison d’être for the 9-minute Vanishing Points, in which Maxime Boisvert and Emanuelle LêPhan (identified in the program as “conceptual hip-hop dancers”) dance their way along the two streets toward the corner, snuggling against the walls of buildings, until they meet. Filmmaker Marites Carino of Canada focuses first on one dancer, then on the approaching other.

A couple of the longer films (13 minutes each) build atmosphere and drama in highly resonant public spaces. Amie Dowling’s Well Contested Sites (a New York premiere) takes place on Alcatraz Island, while Israeli director Daphna Mero sets her Washed in what appears to be a vast industrial laundry. Although Alcatraz is no longer a working prison, its empty cells with their peeling paint and narrow cots, its wide concrete corridors, and its steel grills still bear the imprints of the men once imprisoned there. When Dowling’s large cast of men marches through the hall, the space echoes their steps; they march; they lie down in chains, each grasping the feet of the man in front of him; they roll. “Dance” becomes a symbol of obedience to rules. But Dowling also shows some of them (the principal dancers so to speak) tilting from one wall to the other of a narrow cell, their feet scrabbling against the floor; the doors are now open, but the history of confinement remains. They assist or grapple with one another, their breathing audible, in ways that express in formal, yet powerful ways the relationships and the compressed geometry of incarceration on a mist-shrouded island.

The laundry in Washed is an equally scary place—echoing, full of gigantic washers and dryers that clank and steam. The dramaturgy is a little confusing, but the scenes of two women turning the folding and stacking of apparently numberless white rectangles of fabric (a little too small to be sheets) on a big steel table is mesmerizing. The main event is a gang rape of one of the two by three male workers, worked into a violent sort of dance by camera angles and editing. One woman gets a phone call and has to leave. Apparently only three men and the remaining woman are at this point still laboring in an establishment that looks as if it needs a much larger staff. The initial image is of an as-yet-unidentified woman repeatedly banging her belly against one of the tables; blood is running down her legs. Somehow, perhaps because of its brief duration and unchanging camera angle, this moment doesn’t fully convey what it intends to tell us: she is attempting to end a pregnancy, and all that ensues (including being dropped by the men into an immense dryer before they leave) is a very bad memory.

Lois Greenfield receives her Dance in Focus award from choreographer Elizabeth Streb. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

The gala kickoff to the Festival honored photographer Lois Greenfield, which made me very happy. During many of the years that I wrote a dance column for the Village Voice, Greenfield’s photographs brought what I described to life. Over that time, her work became increasingly adventurous, her Hasselblad camera producing square images, the subjects photographed against a white backdrop bordered in black. Her stills are as full of motion as any film. And at the gala, Let’s Move!, the short film co-directed by Paul Galando (Chair of the Dance on Camera Kickoff Committee) and Callie Lyons, showed Greenfield and her assistants shooting Lyons and other former students of Galando’s in NYU-Tisch’s Dance and New Media project, as they bounced off the walls in her honor.

What a lovely, lovely review. And how sweet to see a photograph of Monica Moseley, who was my friend and left us far too soon. The Slavenska film I saw in very rough form not long after Slavenska died and I’m eager to see the completed version, which I think will be shown on PBS later in the spring. The image of the camera “panting behind” the well-named Benjamin Millepied made me laugh out loud, so Deborah, I beg you, continue carrying on, the longer the better.