Royal Danish Ballet: Principals and Soloists appears at the Joyce Theater, January 13 through 17.

Ida Praetorius of the Royal Danish Ballet in the duet from August Bournonville’s The Flower Festival in Genzano. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

Guess what! August Bournonville has a website (bournonville.com). Since he died in 1879 and didn’t expect the many works he choreographed for the Royal Danish Ballet to long survive, he would undoubtedly be gratified to learn that eight of his ballets and a handful of divertissements weathered the 136 years that have elapsed since his death and are being analyzed in cyberspace by experts (call them trolls and he might—almost—understand). Could he have imagined Abdallah being painstakingly reconstructed in 1985 for Ballet West in Salt Lake City and a version of his last ballet, From Siberia to Moscow being mounted in 2009 on its skeletal remains for the State Ballet of Georgia in Tbilisi?

Until the 1950s, Bournonville’s ballets were largely a Danish secret. Once rediscovered, they attracted an ardent public outside Denmark. A splendid, richly illustrated book by the Danish critic and historian Erik Aschengreen attests to that both in its content and its title: Dancing Across the Atlantic: USA – Denmark 1900-2014. I don’t know for sure how many dance critics, historians, and other visitors, attended the 1979 festival commemorating the centenary of the choreographer’s death; I do recall that those connected with the Royal Danish Ballet were startled by the turnout. At the 150th anniversary of the ballet Napoli in 1992 and at the Bournonville Festival in 2005, the number of attendees from America, Asia, and the rest of Europe reached over a hundred. The city was prepared.

What is it about those ballets and the company that dances them best that led so many of us to make three trips to Copenhagen to see the ballets in the beautiful Royal Theater (built in 1778 and enlarged in the next century)? Why, do I sitting in the Joyce Theater in January of 2015 and watching variations and scenes from Bournonville ballets performed by a small group of RDB principals and soloists, find myself smiling, and later feel tears gathering?

Bournonville’s dances are never about grief. That’s left to the passages of mime and acting. Instead they celebrate happy occasions such as festivals and weddings and parties or define otherworldly nymphs and sylphs for whom dancing is simply a way of life. And that dancing is full of joy and ebullient spirits.

The style emerged in Paris, whence Bournonville and his father, dancer Antoine Bournonville—later a ballet master of the RDB— travelled in the 1820s. Auguste studied at the Paris Opera and for a while performed in its ranks. The steps and combinations that he eventually took back with him to Copenhagen provide the closest glimpse we have of what ballerinas like Marie Taglioni (with whom he danced on occasion) were perfecting in their classes and transferring to the stage. La Sylphide, his only extant tragic ballet, was modeled after her 1832 triumph of the same name, albeit with differing music, steps, and emphasis.

The trio from Bournonville’s Conservatoire, finely danced at the Joyce by Gudrun Bojesen, Diana Cuni, and Ulrik Birkkjaer, shows how different this style of ballet was (and is) from the later Russian style that developed. Although the RDB women dancers now wear pointe shoes, the Paris Opera dancers of the first half of the 19th century wore lightweight slippers darned at the tip and stood only briefly on toe—passing through that stance on their way to something else. But how they could balance and revolve on one flat foot! And how they could jump, beat their legs together in the air, and indulge in all manner of tricky footwork! Seldom did their partners lift them.

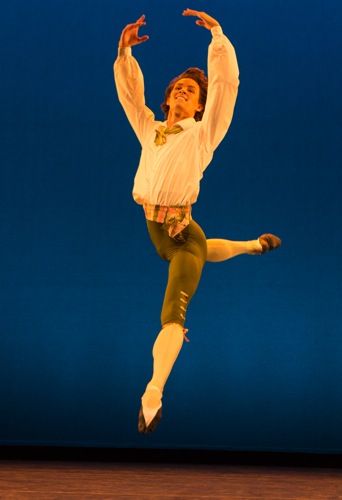

Because in Bournonville’s ballets, the dancers usually hold their arms down and gently curved when they jump, their aerial steps seem to go higher and be less effortful than you might expect, and when they do open their arms or raise them to wreathe overhead, the movement seems more elated. In that wonderful leap that the men most often perform, they advance toward the spectators, with the back leg bent, the front one arrow-straight, and both arms opening as if to offer the gift of their dancing.

The women, perhaps because of corsets they wore in Bournonville’s day, tend to lean their entire bodies to the side, rather than bending at the waist. Also, although the dancers frequently include the public in their gaze, they also glance at what their feet are doing or look at others on stage. Between the big, space-covering steps and the smaller, chattering ones in place, the performers maintain a physical and emotional buoyancy that is as charming as it is spirit-lifting.

Marcin Kupinski and Kizzy Matiakis in the Pas de Sept from Bournonville’s A Folk Tale. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

Birkkjaer, who is also the organizer for this American tour, chose the program wisely. The Pas de Sept from the last act of A Folk Tale opens the evening and Act III of Napoli closes it—two wedding festivities in which all present celebrate the power of love and the triumph of good over evil. In between these are a well-known duet (all that remains of The Flower Festival in Genzano); the short, witty contest for two supposedly British jockeys (the sole choreographic relic of From Siberia to Moscow); the above-mentioned trio from Conservatoire; and Act II of La Sylphide (the dramatic heart of the Joyce program).

At the Joyce, the scenery is absent, and so are the people who usually crowd the stage—the citizens of all ages or the flocks of supernatural beings. After a short musical introduction (recorded), the curtain rises on an empty stage, and the performers enter and begin to dance in simple lighting by Maarten K. Axelsson that suggests a sunlight plaza or a moonlit forest. Yet— amazingly—the behavior and the focus of the vivid dancers summon up the missing populace; they react to invisible others when necessary; those not dancing watch approvingly those who are, occasionally strolling to get a better view. The stage becomes alive with both action and reaction—none of it forced, all of it interesting.

Ida Praetorius and Andreas Kaas in the pas deux from The Flower Festival in Genzano. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

Since women being helped by their male partners to balance on pointe in various pleasing poses wasn’t yet a fixture in Bournonville’s day, his pas de deux present the lovers more as flirtatious equals. At one point in The Flower Festival in Genzano duet, the man balances on one leg, holding on to his partner’s waist; she bourrées in a circle, forcing him to revolve as she does so. A pretty game. Two vivacious young dancers, Ida Praetorius and Andreas Kaas, express both the shyness and teasing boldness of this young pair, as they spring around together, or make nimble statements to each other. All in view of family members and friends who happen to be invisible.

The supernatural domain into which James follows his otherworldly beloved in the second act of La Sylphide is under-populated too. There’s no ethereal sisterhood in long gauzy tutus to confuse him; in addition to the leading sylph, only three frolic in the woods we imagine around them: Susanne Grinder, Kizzy Matiakis, and Femke Slot. Yet on the mostly empty stage, Birkkjaer as the hero and Bojesen as the enchanting creature he pursues make the barrier between these two tragically evident. He craves to embrace her; she cannot be touched (except in one pretty group pose that ends a pas, but we overlook that). No, she gestures sweetly, here, drink this water from my hands; see, a nest of bird eggs you can eat. No kissing.

This tour, sadly, marks Bojesen’s last performances as the Sylph; she is a marvelous one—embodying the sylph’s lightness as she flies across the stage or flutters her arms to show her innocence and kinship with the avian world. Although James’ solos display the hero’s superb elevation—at which Birkkjaer excels—Bournonville didn’t set out to create applause machines, and this eloquent performer shapes his leaps into outbursts of joy. The last of these solos becomes tremendously moving. “Poor, lovestruck fool,” you think–“so young, so full of life!” And the audience alone knows what he is about to discover: he will lose the Sylph and everything else he holds dear. (Those who know the ballet well understand that, when certain music strikes up, James is seeing the woman he was to wed today walking to the church with another man.)

Gudrun Bojesen in the Royal Danish Ballet’s production of La Sylphide in Copenhagen. Photo Costin Radu

The great character dancer Sorella Englund, stumping onstage as the witch Madge to instigate the tragedy, mimes the role magnificently—gloating over James and luring him with the magical scarf that, she claims, will transform the sylph into an embraceable flesh-and-blood woman. Alas, as the sylph’s little wings drop to the ground, she weakens and dies. She forgives her impetuous lover, but shakes a frail finger as if to say, “why couldn’t you have been content with me as I was?”

All this is so vivid that you feeling like chiming in. And the final moment is powerful in its equivocalness. Englund, standing over Birkkjaer’s body, slowly raises her arms in a triumph that must itself triumph over her own surprise, guilt, and sorrow.

For two of the week’s performances at the Joyce, the witch, Madge, in La Sylphide, is being played by a man—not a man in travesty, as is the tradition, but a man in a frock coat (a mesmerist perhaps?). This is the latest version of the ballet staged by the RDB’s artistic director, Nikolaj Hübbe. Bournonville might approve of the complex psychology that Englund brings to the role of the witch. But the male dancer as an imperious warlock? (I’ve only seen a film clip) Or a hint that perhaps James has a secret not-so-heterosexual past.

Marcin Kupinski (L) and Sebastian Haynes in “Jockey Dance” from From Siberia to Moscow. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

Bournonville himself was an admirable dancer, which influenced his choreography. Parisian audiences craved supernatural and exotic heroines and allowed the heroes who sought them to become less important in terms of actual dancing. Bournonville’s men get to dance a lot—tossing off strenuous entrechats, cabrioles, and brisées, spins in the air, and bounding leaps. He also enjoys pointing out their foibles. From Siberia to Moscow’s “Jockey Dance” is like a little vaudeville act. With their jaunty air and fierce competitiveness, the two jockeys “ride” their invisible horses by way of snappy footwork, vie for position, and whip themselves into a gallop. Sebastian Haynes and Marcin Kupinski weren’t always crisp and musically precise on opening night, but they played the hell out of the duet and rode it home.

The festive Pas de Sept from A Folk Tale was further formalized for the American tour. The four women and three men wear all-red outfits, and you can marvel at how cleverly Bournonville deployed the cast in solos, duets, a trio of women, a duo of men, an ensemble, etc. People enter and leave the dancing without leaving the stage, and their sidelines behavior says things like “look at them, will you!” Or “he’s a fine fellow!” Or “well done!”

Suzanne Grinder and Ulrik Birkkjaer as Gennaro and Teresina in the Royal Danish Ballet’s production of Napoli in its home theater. Photo: Costin Radu

The same seven impressive and endearing dancers—Caroline Baldwin, Slot, Matiakis, Praetorius, Haynes, Kupinski, and Gregory Dean—join their colleagues to close the evening with Napoli’s Pas de Six and ensuing Tarantella. There are no crowds of Neapolitans—men women, and children—onstage at the Joyce to celebrate the wedding of the fisherman Gennaro and his Teresina—an especially joyful occasion, since he had almost lost her to a storm, a shipwreck, and a lustful sea god who cast a spell on her. But eleven dancers manage to whip up a festivity that matches that in any village. The only non-colorful element of the scene is the strangely washed-out trim on the women’s frothy white skirts and tight bodices.

Bournonville created sweet pictures with two men (Haynes and Kupinski), each arm in arm with two women (Praetorius, Matiakis, Slot, and (I believe) Grinder. Individuals express their high spirits: Kupinski soaring around in a solo that requires him to drop from a jump into a deep plié and pop up to turn again; Cuni hovering briefly on one toe while H.S. Pauli’s music hesitates and teases along with her; Praetorius bounding expansively around the space; Grinder dancing with a smoother, calmer dynamic.

Once the tambourines appear, the place heats up. Cuni and Kaas inaugurate the Tarantella. Haynes whips off a bit of a hornpipe. Baldwin joins him after she has finished luring Kupinski with her red scarf. The onlookers, including Birkkjaer, smack and shake their tambourines. Kaas makes repeated grabs at Slot’s flaring skirt as she dances (or maybe he’s after the leg beneath). Dean pairs up briefly with Matiakis. The stage seethes with enthusiasm. Amid it, Dean does the solo that belongs to Gennaro, and Grinder becomes his Teresina.

Many Danes are happy to have various directors of the DNB past and present commission new costumes or new scenery for the Bournonville ballets, to update them, to interpolate new bits of choreography. They fear stodginess, crave new ideas. I can understand that, but I do not share their restlessness. We so seldom get a chance to see these ballets that we—especially we dance historians —want to see these Bournonville works—the most authentic vision we have of Romantic ballet—revivified by wonderful young dancers, but not yanked into a modern world where their behavior and morality are strangely out of place. We owe the Royal Danish Ballet and Birkkjaer for reminding us of this and for remembering that these ballets go straight to our hearts.

Oh wow Deborah, thank you so much. I was part of that international press corps in 2005 and this review reminds me of possibly the happiest ten days of my professional life. I especially appreciate your words re the “updating” of La Sylphide; for god’s sake, if it ain’t broke, and it certainly ain’t, don’t fix it. Make something new that reflects our own time and a century from now will still be universal, if you can.

I understand that there might be another Bournonville Festival, in 2018, Start saving…