The L.A. Dance Project comes to BAM with works by Justin Peck, William Forsythe, and company founder-director Benjamin Millepied.

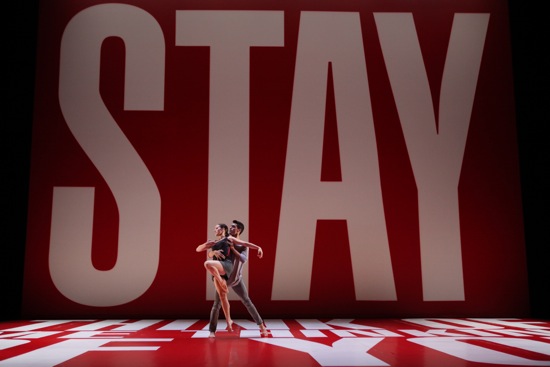

Anthony Bryant and Rachelle Rafailedes of the L.A. Dance Project in Justin Peck’s Murder Ballads. Photo: Julieta Cervantes

What is it about Los Angeles that attracts artists? Even before the 1940s, many European musicians and writers fleeing the Nazis zipped right through culturally confident New York and joined the émigré filmmakers who settled on the west coast. Maybe it was the plethora of sunny days, the scent of eucalyptus and gardenia, the boisterous Pacific Ocean, the possibility of a backyard with an orange tree and a swimming pool. Despite the noisome traffic, those alluring qualities still exist and still draw artists westward.

Climate, of course, may be only one of the factors that drew Benjamin Millepied to found a small dance company in Los Angeles. Nevertheless the kind of company he created fits well into the sprawling city, and he has attracted local funding and support to fuel his desire to collaborate with visual artists and composers in building his group’s rather surprising profile. When Millepied retired from the New York City Ballet in 2011, he had performed major roles in the Balanchine repertory and been a protégé of Jerome Robbins. He had already been choreographing for ten years. But his Los Angeles venture, L.A. Dance Project, is not a ballet company, Although its dancers have all had extensive training in ballet, they are more well-rounded in terms of their backgrounds. Seven of the nine company members are Juilliard graduates, one has a degree from SUNY-Purchase, and all have considerable prior experience onstage. They’re up for choreographic collaboration and creative input.

The two new works that the L.A. Dance Project brought to the Brooklyn Academy of Music’s Howard Gilman Opera House show off their versatility, their dancing prowess, their ease on stage, and their closeness as a group—a closeness that seems to have influenced the choreography of Millepied’s Reflections and Justin Peck’s Murder Ballads.

L.A. Dance Project members (L to R): Rachelle Rafailedes, Stephanie Amauro, Randy Castillo, Morgan Lugo, and (hidden) Aaron Carr and Anthony Bryant in Murder Ballads. Photo: Julieta Cervantes

Peck’s piece is surprising, and these dancers, along with the nature of Millepied’s vision (and, maybe, all those sunny days) may have had something to do with his venturing in a new direction. Hitherto, Peck’s choreography (at least, those dances of his that I’ve seen) has fitted comfortably into the realm of contemporary ballet; he’s still a soloist in the New York City Ballet, as well as a Resident Choreographer there. Murder Ballads is not in the least balletic, unless you count a well-placed arabesque or two, but these are tossed off. It’s a dance with a great deal of loose, springy, athletic movement and impulsive behavior—all cleverly organized and put together.

Contrary to its title, Murder Ballads does not recycle Frankie-and-Johnny scenarios, although you can hear traces of folk songs or a fiddle tune coloring Bryce Dessner’s vivid, sometimes tumultuous score (played live at BAM by the members of eighth blackbird: Tim Munro, flutes; Michael J. Maccaferri, clarinets; Yvonne Lam, violin and viola; Nicholas Photinos, cello; Matthew Duvall, percussion; and Lisa Kaplan, piano). The dance’s visual component by Sterling Ruby is ambiguous, but gorgeous: a variously patterned patchwork of broad horizontal stripes bordered by vertical ones that is reminiscent of certain works by Rauschenberg. Brandon Stirling Baker’s lighting occasionally heats up one or another of the bands

In this setting, two dancers, Rachelle Rafailledes and Anthony Bryant, race onto the stage, dressed for sport (by Peck) and sliding on sockleted feet. One of the first things they do is sit down and put on the sneakers waiting for them onstage. Sneakers for all will be donned and taken off as the dance progresses—perhaps in some highly abstracted reference to leaving no tracks. Here’s another flash-by referral to ballad narratives: Aaron Carr, Morgan Lugo, Randy Castillo, and Stephanie Amauro) bend down and encircle Rafailledes in a kind of human stockade, and, when two strokes on a wood block sound, Bryant knocks sharply twice on the air and then pulls Rafailledes out of the clump. Later, he knocks again near a clump of dancers, but no sound reinforces the act this time, and it has no obvious result.

The six form lines, chase one another into them, peel out from them, pass movements down them. They form arches for others to pass under, and some briefly lie down to be used as structures for stepping on in passing. They form pairs to dance energetically—two male-female ones and a male-male one (no heterosexual ballet conventions here).

They keep their eyes open to what’s going on. Castillo has a terrific solo, in which his legs cross and uncross in some lickety-split ways; Bryant enters and yanks him offstage. Rafailledes catapults Lugo into the wings and shortly thereafter performs a crazy, collapsing, slumping-around passage (shot in the OK corral, maybe). The sometimes argumentative interplay between Peck’s formal structure and interloping flashes of disorder and drama are intriguing. I like the fact that when Bryant and Rafailledes finish a duet, they just pick up the shoes they’ve removed and walk cozily away together, as if they’ve come to an understanding, and it’s time to go home.

Millepied plans to make his Reflections the first part of a tryptich entitled Gems (it was commissioned by Van Cleef andf Arpels). A latter-day echo of George Balanchine’s Jewels? Hmm. The dance as is fills around forty minutes, and its first section is as long as the others put together. Is there such a thing as a West Coast sense of time? You can also feel a kind of leisureliness in the music: selections from Davis Lang’s This was written by hand/memory pieces that Lang and Millepied chose together. For a long time, pianist Andrew Zolinsky plays single notes, spaced out so that they could be drops of water plinking into a pond. Then he settles into a repetitive pattern for a while and builds in complexity from there. The music coincides with the dance, rather than working intimately with it, as does Barbara Kruger’s striking set. Her projected design fills both the backdrop and the floor. Huge red letters loom above the stage, saying either STAY or GO. The message that continues along the floor in smaller letters: THINK OF ME THINKING OF YOU.

The process of mounting a revival of Merce Cunningham’s astonishing 1959 Winterbranch for the L.A. Dance Project a couple of years ago may have expanded Millepied’s ideas about collaboration. Perhaps the music, dance, and visual components of Reflections are to be understood as separate strands, resonating sympathetically with one another. Too, Millepied choreographed the piece in collaboration with its original cast: Lugo, Julia Eichten, Charlie Hodges, Nathan Makolandra, and Amanda Wells.

L.A. Dance Project members in Benjamin Millepied’s Reflections. (L to R, foreground): Morgan Lugo, Rachelle Rafailedes, and Nathan Makolandra. (At back): Julia Eichten and Aaron Carr. Photo: Julieta Cervantes

Millepied’s early ballets were fastidiously constructed but stuffed with steps; he was bursting with ideas and youthful vigor. Reflections is hardly minimal, but it does allow the spectator time to ponder what’s happening onstage, even dares to tax his/her attention span. Another development in his work, I think, is the tenderness that crops up in this piece. The long duet between Eichten and Lugo seems to be one of discovery. They pull on each other, draw close together, watch each other try things out. He scrabbles for a while on the floor while she stares. She runs and jumps onto him. Things like this occur and recur in various ways. But what’s striking is the flow of tenderness and physical closeness that permeates this relationship. The two are fond equals, with more than a bit of sexual heat.

What you notice as the dance progresses is that the men are not presented as macho or even as stalwart partners. They are as silky in their dancing as the women—even, at times, more so. The section with the swiftest pace and sharpest edges is a solo tailored to the inimitable muscular crispness that characterizes Charlie Hodges’ personal style (Hodges is recuperating from an operation and did not appear at BAM); even danced by the more wiry, loose-limbed Carr, the solo is a virtuosic display of spins, jumps, and fast footwork. But after this, Carr and Lugo (who has an easy fluidity, an unselfconscious lyricism) dance companionably, even affectionately together. And in the last section of comings and goings—after a fairly sharp, fast-moving, conversational duet for Rafailledes and Makolandra in shifting areas of light—Lugo and Makolandra enter, bending forward slightly and making flowery gestures with their spread fingers, then back out, continuing the flourish.

There’s a quite a bit of jumping in this last group section, but also embracing and collaborating on joint structures or games. In the end, only the two women are left onstage, sitting on the floor and nestling together.

An earlier L.A. Dance Project cast in William Forsythe’s Quintett. (Foreground): Nathan Makolandra and Julia Eichten. (At back): Charlie Hodges

I wrote in some detail about L.A. Dance Project’s production of William Forsythe’s 1993 Quintett, when the company was featured on the Peak Performances series at Montclair State University (https://www.artsjournal.com/dancebeat/2012/10/east-to-west-to-east/). It was presented then on the same program as Cunningham’s Winterbranch and Millepied’s Moving Parts. This is the dance that Forsythe created as a tribute to his wife, dancer Tracy-Kai Meier-Forsythe, who was dying of cancer (her life ended in February, 1994). It honors their love, her strength and courage, and the sometime fierceness of grief. The strange black object that sits onstage might represent all the paraphernalia of hospital machines (it is supposed to create clouds at the end, but I didn’t see that happen this time).

The five dancers (Rafailedes, Eichten, Makolandra, Lugo, and Castillo) come and go in a harshly lit black void, while composer Gavin Bryars’ loop of a derelict man singing in his frail, hoarse voice, “Jesus’ love never failed me yet. . .” gradually moves from being barely audible to full volume. In the choreography, as is always true of Forsythe, beauty and power dispute with awkwardness; non sequiturs; and strange, mannered encounters. There are beasts prowling in these people’s bodies, pouncing without warning. You wonder why Rafailedes wears a very short, floating shift over skin-colored tights, so that she appears, disquietingly, to be partially naked. But there’s no point questioning why people enter the action and leave it seemingly arbitrarily. Nor why, when some people are watching others, they crouch and swing along like monkeys. Perhaps we are seeing into nightmares or the phantoms of disease.

When Makolandra performs—magnificently—a long, ribbon of complex motions, his long limbs stirring the space for what seems like miles around him, spectators want to, start to, applaud. But Quintett is not that sort of dance. You see people fall, lie still for a long time. Rafailedes moves as if hobbled, then dances beautifully, collapsing and rising.

This November, Millepied goes to Paris to take up a new position, director of the Paris Opera Ballet, a very different sort of organization. Even though he will be often absent from Los Angeles, he affirms that the L.A. Dance Project will continue—strong in its direction, its adventurous choices, and its band of magnificent dancers. Rooted in California soil.

Los Angeles in the Thirties and Forties was hopping with creativity, which is why my sculptor father dragged my New Yorker mother (she was a convert, came from Michigan, and passionate about the city as converts tend to be) across the country to settle there in 1935. And there wasn’t the competitive pressure, unless you were involved in the movie industry, that there was in New York even at that time. I don’t really think climate had much to do with it then, though it may well now. I find this review extremely interesting, as usual, for the vividness of the descriptions, but I have to say that when the company performed here in Portland a couple of years ago, the best part of the show was “Winterbranch,” and while the dancers were terrific in everything they danced, Millepied’s choreography left me cold.