The Soaking Wet Festival at New York’s West End Theater, October 2-5.

Bored house guests. What does that mean to you? Unearthing the jigsaw puzzle because it’s raining and you can’t take them to the beach? The duet Bored House Guests, dreamed up and performed by Sara Hook and Paul Matteson as part of the Soaking Wet Festival, blasts open any of the usual images. Is the “house” in fact a home, or is it a theater—perhaps the tiny West End Theater, nesting two flights up in the Church of St. Paul and St. Andrew, where these two brilliant performer-choreographers are puttin’ on a show? Or is the “house” the relationship they are locked into? Or the struggling, posing, sweating bodies that contain their rampaging spirits?

When the spectators enter the tiny theater with its fraying red velvet seats, Matteson is already sitting motionless in a silver armchair in a patch of light (lighting design by Jay Ryan). The chair is placed as far as possible from the first row of the audience. That’s not very far; calling the West End Theater “intimate” doesn’t adequately describe the small, curving performance space with its vaulted ceiling.

Matteson has been sitting there for about 15 minutes when a loud noise in the hitherto restrained musical score by Nick Didkovsky prompts him to take off his shoes and stand on tiptoe, wobbling slightly. Hook walks in and stares at him. From the outset, this be-spectacled woman—tight-lipped, occasionally exasperated—attempts to maintain a kind of world-weary dominance. The man often looks at her as if to say, “What will she do/want next?” Who are these people in their black pants and tacky shirts? We may never know (although deep down, we probably do).

What passes between Hook and Matteson is structured vaguely like a series of “acts,” or attempted feats. Or rounds in a competition or forays onto a dance floor. But much of what materializes deteriorates almost as quickly. Throughout Bored House Guests, polite gestures recur—an offered arm that says “this way, please” or “you first;” or “may I present?” Hook and Matteson bow: link their arms like pairs skaters; move into a ballroom hold; lifts wreathed arms to resemble ballet’s-fifth position port de bras. However, several times, Matteson walks doggily on all fours, and once Hook actually plays the dog, jittering toward Matteson on all fours, then backing up a little, then coming forward again, while he, crouching, says things to her we can’t hear.

Four of the musical pieces that accompany the dance are by Didkovsky, with the remaining three credited to Didkovsky and his hardcore band Vomit Fist (these last are titled “Sodom,” “Enter My Guts,” and “Frogmen”). Once, a crackly, off-key voice sings “Let Me Call You Sweetheart,” a song that is later reprised, roaring and buried in an indeed vomitous storm of sound. Matteson echoes that image toward the end, crawling, convulsing, and spewing out strangled noises. And Hook has a solo from hell, thrashing around as if she intends to break herself into pieces.

Some of their encounters have a surreal edge and/or a tinge of farce. Matteson rushes toward Hook while she’s maintaining a gracious, open-armed, wide-legged stance, slams himself down on his knees and glues himself along one of her legs—suggesting for a few seconds one of those dogs that embarrasses its owner by humping a guest’s calf. She maintains her poise as long as she can, while he gets her leg gripped between his and starts maneuvering the two of them into improbable, anti-erotic (or failed erotic) positions. In another moment—one with a comic twist—she jams her head against his chest and sticks it there, then slides one perfectly arched foot and then the other into a balletic tendu to the side.

Paul Matteson about to slam onto his knees before Sara Hook in their Bored House Guests. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

I think Matteson is one of the world’s great dancers (I’ve missed seeing him in the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company, which he graced for four years). In one amazing solo in Bored House Guests, his mastery of the large and loping and the small and particular, and how they may both mesh and interrupt one another is uncanny. You have no idea what’s going through his mind, or what he sees in the distance, but clearly something is. You follow him through his every hesitation, outburst, change of mind, easing of body.

Midway through the piece, he and Hook become daringly physical. She jumps at him from behind, chest-bumping his back over and over; she leaps onto his shoulder and sits there awkwardly triumphant; he stands bent forward, one leg on the ground, one in the air behind him, and—while she balances on his back—he revolves (!). Slightly out-of-synch drum rolls announce these feats. The effect is of a domestic battle as a pas de deux gone wrong—and a pas de deux that’s more obviously arduous than its well-behaved ballet cousin.

Near the end, Hook, who has left the stage for a few moments, returns with her wild hair in a bun and her feet encased in glittering, high-heeled silver boots. Matteson opens a bottle of champagne, and they sip some. But it ain’t over till it’s over. Hook removes Matteson’s shirt and tucks it into the waistband at the back of her pants. When she leans perkily over one side, then the other, of the chair in which he’s again sitting, the shirt becomes a bird’s showy tail. And then (did I really see this?), she leans over and licks one of his nipples.

Also, wearing those cruel boots, she tries to stand on his thighs, and pretty soon succeeds. Finally, he reprises some of his dancing, puts on his shoes and walks out, leaving her standing there in the dimming light.

Hook and Matteson’s amazing duet constituted the 8:30 show at the West End Theater. At 7:00, a smaller audience assembled for a joint program of small-scale works by Seán Curran, Malini Srinvasan, and Daniel Holt. (Blakely White-McGuire was scheduled to perform a solo by Deborah Zall, but illness prevented her doing so). Valerie Gladstone curated this particular event, but could not be there to moderate the discussion following it. David Parker, who took her place (he and Jeffrey Kazin of the Bang Group present the annual series), put forth some possible connections between the offerings, but I was also struck by how different they were.

Elizabeth Coker in Seán Curran’s Better to be Looking at It Than to be Looking for It. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

Curran (my colleague on the dance-department faculty at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts) was adept at Irish step dancing well before he performed (for many years) with the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company and founded his own group. His own choreography is often refreshingly foot-lively—as it is for the solo danced by Elizabeth Coker. The title is instructive: Better to be Looking at It Than to be Looking for It. No story, no “meaning” beyond the sight of a strong, assertive, good-humored dancer working her way through strenuous variations set to the ravishing No. 2 of Franz Schubert’s Moments Musicaux for solo piano (alas, played live by Jonathan Matthews at all but this first performance).

Coker may clap her hands gently together to match two notes that conclude a Schubert phrase, or make two-dimensional, flat-handed arm gestures that hint at Balinese dance, or press her palms down on the air to signify the end of a variation. Nevertheless, it’s her legs and feet that are busiest. She covers the limited space with swift, grounded steps or bigger airborne ones, clicks her legs together, swings one leg forward and back. She calms down when Schubert does, becomes more tempestuous when he works himself up to that, but she doesn’t yield to mood the way she responds to tempo and complexity. She gazes challengingly at the audience whenever she faces front. You want to say, “I am looking at it and I’m liking it. Hidden meanings? I’m swearing off those.”

Curran also contributed Duet Event to the program. In this, Dwayne Brown and Jin Ju Song- Begin dance to selections of music by Radiohead. He wears a micro-pleated red outfit, she’s in blue, and their initial relationship is hard to parse. For sure, they are ceremonious with each other as they spool out strong, smooth, moderately paced moves. They move in unison but not in perfect synchrony (or maybe I mean harmony). The middle section brings them together in a resonant shared task; with their arms or legs, they create cavities and tunnels for each other to pass through. It’s a subtly flawed relationship, I’d guess. At the end of the third section, she’s supine with her hands raised as if to catch him. He lies elsewhere, near enough, but not really close.

You need to think about meaning when watching Srinivasan perform Pannagendra Sayana, a solo that she has choreographed in India’s Bharata Natyam style (with a few subtle departures). Maharaja Swati Tirunal’s recorded score blends flute, violin, inger cymbals, and drum (mrdangam). A vocalist sings the text. It is this text that Srinivasam explains in words and gestures as a prelude to the dance, and, even in this small space, I’m not sure everyone can hear her gentle voice. I sense that she’s nervous, and it takes her a while to become as bold as she needs to be. When that happens, the tensions among desire, frustration, and adoration become wonderfully clear.

This is one of those familiar sacred situations in which a beautiful woman, exemplifying the soul, yearns for a god to visit her. She waits through eight stages of night for his coming, as ardently sensual as a girl hoping for her lover to appear. The god in this case is Vishnu. Srinivasan’s fluid gestures and facial expressions convey her feelings and the images in the text, while her passages of rhythmically intricate stamping create another, more abstract form of expressiveness. She makes you see by her undulating arms the snake on which Vishnu reclines; forms with her fingers his lotus-shaped eyes and teeth like jasmine buds; depicts cuckoos, then covers her ears and grimaces (no music sounds sweet if Vishnu is not with her). But she also conveys, over and over, her mounting impatience—she looks for him in the distance, thinks she heard him, is disappointed yet again.

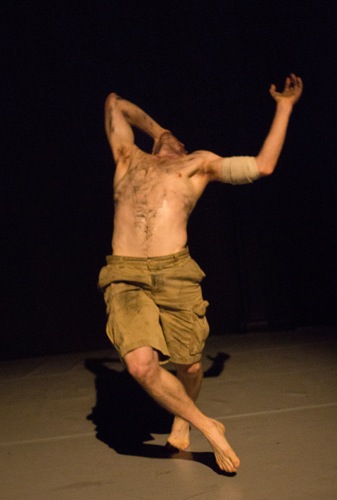

Daniel Holt calls his astonishing new solo Crusoe. And although in the talk-back he termed it abstract in relation to his previous work, I think perhaps he uses that sometimes misleading word to mean what George Balanchine meant when he told an interviewer that his ballets were not abstract but “storyless.” When the lights begin to glimmer, and you see a man standing motionless—his feet apart, his knees slightly bent, his body hunched protectively, and his eyes staring unblinkingly forward, thoughts about his possible identity or situation slink into your mind. As the lights brighten a tiny bit, you notice that his face, bare chest, and knee-length shorts are dirt-stained, and that a bandage is wrapped around one arm.

A human being on stage can never be as “abstract” as a musical note. Given the title and Holt’s imagery, we imagine “castaway” and “desert island.” And that’s obviously okay with him.

What’s compelling about the character he presents is the way he sometimes seems to be investigating how his own body can move incrementally, and sometimes become the recipient of forces that knock him off-balance and set him staggering. The music he begins with is by Haan 808, an eerie blend of water lapping and transformed musical sounds that could presage storms (later Ancient Astronaut and Francis Harris contribute other environments—percussively rhythmic or ringingly electronic).

I say “begin,” but Holt is motionless for many minutes before he begins to make small adjustments—a rolling of one shoulder, a circling of his neck, his belly, his hips; watching him is like watching an unfamiliar machine beginning to warm up. As the complications he has set up in his torso quicken and expand, they form a network of fluent movements offset by jerks and stutters. And he’s still standing in one spot.

As he starts to explore the space around him, he sometimes appears creaturely—simian maybe. And he’s attentive to —appears wary of— what’s out there or above him. He falls, scrabbles on the floor; his own hand hits his head, and he recoils. He makes faces too, as if trying them out: a wide open mouth, a toothy grimace. In the final dimming light, he rises from crawling arduously on his belly to stand again, however unsteadily, amid the recurring sound of waves.

Holt, who currently heads the dance collective Dirt, came to hip-hop late, after training and working in ballet and modern dance. He is one of those (Kyle Abraham is another) who can weave the evasive mobility of hip-hop styles into more experimental, personal and (dare I say it?) dramatic forms expressive of today’s uncertain terrain and mobile structures. Mesmerized by Crusoe, I feel as if I’m seeing a human battling, on a small, intense scale, himself, the elements, and his fate.