Dorrance Dance taps out a world premiere at Jacob’s Pillow July 16 through 27.

Michelle Dorrance in ETM: The Initial Approach. Behind her: Demi Remick and Caleb Teicher. Photo: Christopher Duggan

These days, we’re all wired. Or wirelessly connected. Sometimes walking down the street, I play a private game called “What would Mozart think?” Would he, for instance, worry that people walking along the street with things in their ears, talking loudly into the air, were lunatics? On the other hand, would he get down on his hands and knees in Jacob’s Pillow’s Doris Duke Theater, regardless of his silk breeches, and try to figure out how a piano note could emerge when a dancer’s feet hit a wooden platform. He’d have a lot of catching up to do, and I might not be much help.

Michelle Dorrance is way ahead of me. Not content with being a super-star tap dancer and a highly original choreographer, she has, in collaborating with Nicholas Van Young, entered new territory. It involves a lot of wires. In addition to being a dancer, choreographer, and musician, Van Young is an instrument creator. For Dorrance’s brand new ETM:The Initial Approach, with the aid of the live performance software Ableton, he has created a living set that responds sonically to the dancers’ steps. He said in his program bio that he had had visions of “several dancers across a number of platforms and boards. Dancing out elaborately choreographed phrases while simultaneously playing the musical composition.” Dorrance helped to make that vision a reality.

The title “ETM,” or Electronic Tap Music, is a play on EDM, Electronic Dance Music, and I can’t say that the aural landscape of Dorrance and Van Young’s mind-blowing piece constitutes great music (from a musical point of view) on its own. But the connection between splendid tap percussion and the additional sounds or melodies it may generate is fascinating.

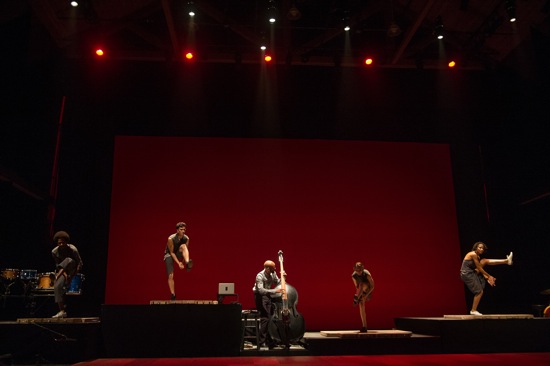

Michelle Dorrance and Nicholas Van Young’s ETM: The Initial Approach. (L to R): Leonardo Sandoval, Caleb Teicher, Greg Richardson, Demi Remick, Karida Griffith. Photo: Christopher Duggan

A man sits at a computer, all but hidden behind a row of wooden platforms of difference heights that fill the stage from side to side (I assume this is Donovan Dorrance, billed as “Controllerist”). Michelle Dorrance introduces us gradually to what we’re going to want to understand: parts of these platforms, and others that are carried on in blackouts between sections, are simply mic’d wood; others can serve as triggers for a variety of instrumental sounds that make up a composition. These sounds can be looped and layered, added and subtracted. We may hear the terrific tappers’ feet hitting the surface in complex ways, but the same feet may also contribute to an instrumental texture by touching certain pads or areas in simple repetitive rhythmic-tonal patterns—say to provide a back-up chorus for a soloist’s virtuoso turn on the floor in front of the platforms. In one sequence, performers add clapping and slapping to their steps. In another, their feet have a conversation with Dorrance’s solo.

Seconds after the ETM:The Initial Approach has begun, Warren Craft steps onto the furthest stage-left platform and plants one foot and then another in a lunge. Each step triggers a deep drumbeat. Now we get it. They are marvels these dancers. Sometimes the movements are choreographed (mainly when unison is desirable), and at other times the performers are improvising. Occasionally four of them—say, Karida Griffith, Demi Remick Leonardo Sandoval, and Caleb Teicher—on separate platforms—feet working, limbs flying—will each contribute distinctive rhythmic elements to create a complex visual-aural polyphony.

A small, low-to-the-ground platform plus trigger boards is brought in for Van Young to solo on, while vocalist Aaron Marcellus sings at him. The post-performance talk reveals that the white object in Van Young’s hand is a wii controller; he can press buttons while dancing to change the sounds that the pads will emit. (We also find out that all those sounds have been extracted from a recording of Marcellus’s song, chopped up, and repurposed.) Van Young, a cast member of Stomp for nine years, is a powerful dancer.

A small row of trigger boards plus a piece of equipment with dials is laid out for a solo by a guest artist, b-girl Ephrat “Bounce” Asherie. In between flip-overs, spins on her back, and other nimble, close to the floor moves, she slithers over to twist the knobs that determine her accompaniment. Behind her, Dorrance taps a quiet sympathy.

Musician Greg Richardson also plays an important part, switching between double bass and guitar, building sequences loop by loop. Sometimes Van Young does some drumming, along with Craft. As the performers come and go, join and separate (in rhythms if not in space, since they’re sometimes confined to the musical platforms), we become more sensitive to the textural changes. Once Remick, Teicher, Craft, and Dorrance perform simultaneous individual sequences on small boards, each of which has a strip of patterned metal on one edge. Now their tapping acquires a punctuating rasp every time they drag a foot across it. They also pull heavy chains from behind these surfaces, hold them up by one end and drop them in synchrony; the chains sputter into trills against the wood—competitions for the fastest tapping ever (gimmicky, perhaps, but very effective).

The piece is beautifully engineered for contrast and consistency and flow. In one passage, the dancers—one after another—fly across the space, tapping as they go. Each gets numerous chances to shine. Dorrance, of course, is a marvel of intricate footwork, performed with almost goofy ease and good humor. Craft, with his lean sinuous body (he gets to join Asherie briefly) is a fascinating performer, and all the dancers (including Sandoval, billed as an understudy, but pressed into service) present themselves as terrifically skilled individual stylists who are also able to fit into a killer ensemble. And Kathy Kaufmann’s lighting plays a vital part—isolating the platforms, coloring the atmosphere, directing our attention, and setting moods.

Amid all the dancerly skills and technological wizardry, one thing bothered me. The songs that Marcellus sings intermittently provide a valuable soft side to the atmosphere of the piece. However, his voice has been somewhat electronicized, blurred by aural mist. It’s often hard to hear the words, and the sound doesn’t appear to be coming out of his mouth, but from a speaker high in the house. The result is eerily distancing. None of the electronic effects intrinsic to the piece conceals the down-to-earth sound of tappers tapping as they usually do; I wished I could more often hear the singer singing as he usually does.

What do you say, Amadeus? Hey, put that controller down!

Nice work, Deborah. I read a couple other reviews, all positive, an interview with MD in Boston Globe. You definitely take the prize for description. I can see how Murray and your son and you all have musical vision that appreciates tap for its real sake and the choreographers don’t have to constantly spell out, “We are musicians too!” all the time. Or as Gregory Hines said, Tap is unique in that ‘you see the dancer move and you hear the dancer move.” (not unique to tap; there are other “foot cultures of the world such as kathak, Flamenco etc…..”

Al De Sio invented tap tronics and I’m not sure why G Hines didn’t explore it more in the movie “TAP!” where each sound came out not a tap sound. Anita Feldman explored this as did that modern dancer, who used to dance with the balls.

Some of them always got tripped up on their wires. But this doesn’t sound like that kind of thing. I wonder when Nicholas Van Young added the “Van”. It’s cool, but he wasn’t always that at all. He has a very very cool mom in Austin who has the same “hippie” background a bunch of us still have.

I love your writing on this one in particular (I wonder why? Duh), and it sounds like something “new” is happening. I miss the comedy although Michelle herself is humorous and as far as I know doesn’t take herself too seriously. I can imagine some of the old masters (whom Dorrance is influenced by) ‘getting it” and some yearning for more jazz A Trains. Although I’ve been a fan of Dorrance ever since I saw/heard her, and watched her amazing luminous rise, (she’d have been a movie star for sure a an Ann Miller or E Powell in the 30s or 40s), so embracing is she. Additionally she has that post something won’t say “modern” head that makes her so inviting. I wonder how many people want to study tap after seeing something like ETM: The Initial Approach” (Love that title), I could go on and on without even having see the show (yet). I hope it comes to NYC.

I was thinking just last night that the future of dance would be so wild that anyone of the baby boomer generation could not possibly conceive of it. Only in my dreams.

The Flying Karamatzov Brothers used to work with a version of this technology several years ago, so that their (fairly rudimentary) tapping combined with the rhythm of their juggling. For them, it was a vaudeville-flavored stunt (and an impressive one at that), but I’m so glad to hear about someone who is exploring this in a more complex and nuanced way.