The Trisha Brown Dance Company moves through its final three years.

Trisha Brown’s Set and Reset. (L to R): Megan Madorin, Nicholas Strafaccia, Neal Beasley, and Tara Lorenzen. Photo: Cory Weaver

It has only been a few months since I wrote about the Trisha Brown Dance Company, and here I am writing again. Ever since it was announced last year that health issues had caused Brown to retire as company head and sole choreographer and that the dancers were embarking on a three-year farewell tour, I tend to think, “It may be the last time I’ll see this dance.” The thought hurts.

So of course I attended one of the company’s performances at Bard College’s Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts. In this series, billed as Proscenium Works 1970-2011, which opened Bard’s Summerscape 2014, associate artistic directors Carolyn Lucas and Diane Madden chose to present works that Brown created for the proscenium stage (as opposed to those she made in earlier years for black-box theaters, museums, or outdoor spaces). I’ve loved Brown’s mind, her playfulness, her wit, her daring formal innovations, and her agile, fluent self in motion ever since the late 1960s.

A black-and-white film by Babette Mangolte is playing in the lobby. It’s Brown dancing her 1978 solo Water Motor in 1978. (See http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=it-iMn46ebw). The small onscreen figure is a marvel. An inner motor indeed propels her, and water is something that she excels at. Currents flow through her body and limbs, sometimes in contrary directions. From poised stability, she flings herself—or is flung—into motion. She may gallop like a frisky horse for a second before one of her legs decides to swing across her body in the opposite direction and pull her with it; ripples ensue. A complex process of folding and unfolding seems to be going on. Imagine throwing a shirt of yours into a stream and watching how it transforms its outlines even as it adheres to its basic structure.

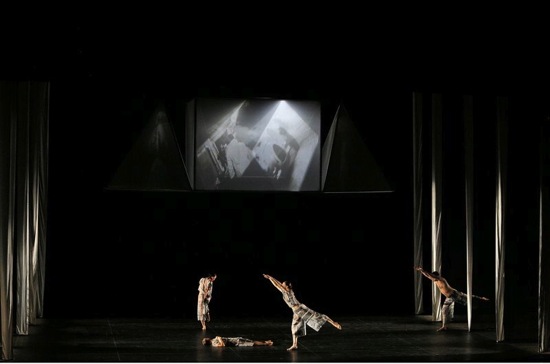

Inside the theater, the company is performing Set and Reset (1983), If you couldn’t see me (1994), and I’m going to toss my arms over there—if you can catch them they’re yours (2011), Brown’s last work. Any dancer performing in a Brown dance has to be wily and smart, as well as technically assured. Inevitably, for me, Set and Reset is a kind of palimpsest. Through these dancers I see glimmers of the original cast—Brown herself with Eva Karczag, Vicky Shick and Stephen Petronio, Randy Warshaw. . .but that’s only because Brown created the movement material on their bodies and with their collaboration. The functions and directions that govern the result differ with different casts. So this version is not identical to the original, but it is essentially and unmistakably the “same” dance. As company member Neal Beasley said in the post performance Q & A, he is not Randy Warshaw, but in his own indelible and dedicated way, he plays by the rules.

Set and Reset beneath Robert Rauschenberg’s decor. (L to R) Cecily Campbell, Tara Lorenzen, Jamie Scott, and Neal Beasley. Photo: Cory Weaver

Robert Rauschenberg’s set has its own retrospective aspects. Amid the montages that flit across the three structures that rise to hang above the dance, are glimpses of reel-to-reel tape recorders, headlines gone by, and old movies. Similar images are also imprinted on the costumes, but, what with their filminess and the dancers’ constant motion and comings and goings, you can’t “read” the attire. The filmy curtains hanging at the sides never conceal the performers completely and often flutter in the wake of an entrance.

Your eyes are kept busy—now snatching comfort from unison, now watching one dancer echo another for seconds and move on, now seeing simplicity evolve into complexity via new congruences in similar material.

Not all the dancers cluster in a far corner when Set and Reset begins.. At least, I don’t think so. Somewhat later, here comes Tamara Riewe to join or spell Beasley, Cecily Campbell, Megan Madorin, Jamie Scott, and Nicholas Strafaccia. Later still, Tara Lorenzen arrives, then Stuart Shugg. They’re all beautiful in Beverly Emmons’s inspired lighting (created with Rauschenberg). Laurie Anderson’s marvelous score, Long Time No See, buoys up the elastic ripples of dancing, with her own voice chanting the title and rhythmic syllables in an ambiance that includes robust rhythms, bell-like sounds, and echoes.

At Bard, on June 27 and the matinee of the 28th, Cecily Campbell, one of the newest members of the Trisha Brown Dance Company, performs If you couldn’t see me, a solo Brown made for herself, while Scott performs it on the evening of the 28th. For this, Rauschenberg created the costume, the music, the lighting (with Spencer Brown) and the visual design. The latter, I assume, means that it was a suggestion of his that induced Brown to perform the entire solo with her back to the audience.

It was quite a back. The white costume, with its split skirts reveals not just the dancer’s legs but her spine and its surrounding muscles as she traverses the stage from side to side. In a sense, the movement—reticent and sharp-edged as compared to that in Water Motor—is a gentle battle between three-dimensionality and the prevailing two-dimensional view. Every circular whip of Campbell’s leg or curling around of her arms suggests that the impulse may pull her body around with it, but it never quite does. In Trio A, the solo made in 1965 by Brown’s colleague and friend, Yvonne Rainer, the performer averts her gaze from the spectators, sabotaging any likelihood of charming them. In If you couldn’t see me, we may glimpse Campbell’s cheek for a second or two, but never her full face. You may, if you like, imagine an invisible audience beyond the back of the stage with a different perspective. Campbell performs the solo with fine sensitivity, accuracy, and fluidity.

I’m going to toss my arms over there—if you can catch them they’re yours (known to the dancers, and now to me, as Toss) is a much simpler work than Set and Reset. By “simple,” I only mean that the basic material is less complex on the body, clearer in terms of lines (you become very aware, in fact, of arms—especially of arms swinging straight from the shoulder).

The clarity is true of the dance’s spatial patterns too. Susan Rosenberg mentions in her program essay that the opening movement phrase developed from instructions derived from one of Brown’s drawings: “curling, curving and backing up.”

Members of the Trisha Brown Dance Company in Brown’s I’m going to toss my arms over there—if you can catch them they’re yours. Photo: Cory Weaver

Composer Alvin Curran plays portions of his vivid score, Toss and Find, on an upstage piano, while other musical passages and sounds provide an electronic layer. I hear voices singing, what could be bagpipes, an accordion (or maybe a harmonica). The back wall of the stage is bare, but at stage left sits a bank of large fans (visual presentation by Burt Barr), and all the fans—of various sizes and colors, many gleaming in John Torres’s lighting—are switched on, their whirring adding to the aural texture. They also create aisles in which the dancers may perform and through which they enter and exit.

I’m more aware of the role played by Kaye Voyce’s costumes than I was the first time I saw Toss—perhaps because I was initially so moved by the possible metaphor of Brown divesting herself of her dances. But the outfits—white pants with bulky white tops that fly open at the back to reveal flashes of color—are props as well as clothing, and their gradual removal uncovers the bodies of the dancers and alters the image of the movement. By the end, the four men (Olsi Gjeci joins the others) are wearing what look like jockey shorts in different colors, while the women are clad in what could be bathing suits (also individualized in terms of color).

To remove the tops, the dancers have only to pull and shrug a bit and they’re free—butterflies shedding the cocoon. Once the blouses are tossed, the fans blow them along the stage floor. Beasley’s, the first to be discarded, ventures over the edge to lie inertly in the aisle. Others may remain onstage, still others are blocked by the proscenium arch; some escape.

The choreography offers up a typically Brownian mix of synchrony and dissimilarities, of solitary forays and assisted vaults. You can focus on such brief events as the men dancing with one woman, Jamie Scott, and then Scott and Beasley moving in unison, with no one else onstage. You be become familiar with recurring moves—the flipping of a hand or the swing of a leg This is a diligent community of equals, of magnificent dancers working together—tossing out skeins of movement, catching them on the run. Windblown, yet enduringly stable.

Deborah, I love this:

“Imagine throwing a shirt of yours into a stream and watching how it transforms its outlines even as it adheres to its basic structure.”

That is such a great image for a reader who hasn’t seen Trisha’s work and such a delectable one for anyone who has.

Brava!

The title “If You Couldn’t See Me” carries a poignant weight, now that indeed we can’t. I loved, truly loved, seeing Trisha Brown perform that speculative solo, the use of her limbs it seemed to me investigative–“is that my leg, extending to the side?” But is my failing memory really failing me here? What I remember is a dress, slit up the sides, no trousers. Or has the costume changed? Thanks Deborah for this writing.

It is not Martha Ullman West’s memory that is at stake. You would think that, at least, the image of Cecily Campbell that accompanies this review would have set off alarm bells in my head. Of course the costume for “If You Couldn’t See Me” was and is not pants but a dress–or rather, the front and back panels of one. I’m making the correction immediately.