Jacqulyn Buglisi, Elisa Monte, and Jennifer Muller share a program at New York Live Arts, June 18-21.

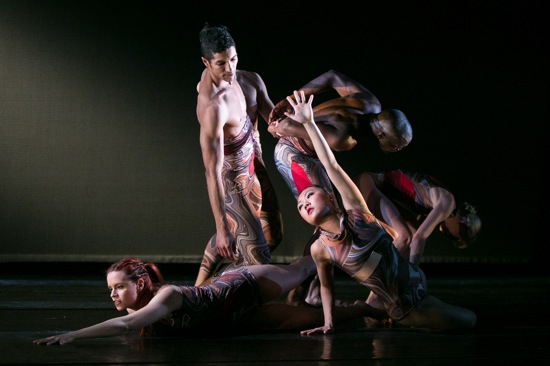

The cast of Jennifer Muller’s Miserere Nobis in Monte/Buglisi/Muller Live. (Left foreground: Seiko Fujita and Shiho Tanaka. Photo: Carol Rosegg

If you’re wondering about people who have had long, productive careers in dance, you might want to consider Jacqulyn Buglisi, Elisa Monte, and Jennifer Muller (note the alphabetical order). First came their years as marvelous dancers—Muller in José Limón’s company and then in Louis Falco’s, Monte and Buglisi with Martha Graham. All have maintained their own groups for several decades, toured them extensively worldwide, and choreographed pieces for other companies. They have developed their own voices; that is, you can’t call their work Grahamesque or Limónish in terms of movement style.

Their success is understandable. They all employ strong, handsome dancers, and all create works in which contemporary or universal concerns mate with large-scale virtuosic dancing and dramatic expression. Whoever first thought of bringing these three artists together in a program at New York Live Arts should be congratulated.

It seems to me that the dances made by these women are finest when the movements spring from the emotional or societal base that motivates each. By this reasoning, the pieces threaten to become unstable when dance moves aren’t anchored firmly to the idea behind them—when, say, a person wishing to get close to another on stage takes the time to lift a leg in an arabesque or some other step that calls attention to itself. In one of Muller’s favorite moves, a dancer lifts a slightly bent leg high to the side by putting one arm under his or her knee; it’s great-looking move but not always relevant.

Occasionally, too, passages can be confusing or misleading. For instance, at one point in Monte’s Lonely Planet, the eight dancers start to follow one another in curving patterns; as they snake around in their line, they pump their hips forward with every deep forward step, and inevitably individual quirks call to mind a fashion show parade. You think, “what’s that about?” in a piece that concerns the loss of human connections in a technological world.

One of the most pungent works on the program is Muller’s brand new Miserere Nobis, set to Samuel Barber’s arrangement of his famous Adagio for Strings to include voices singing the “Agnus Dei” of the Mass. For this, Muller uses a spare vocabulary, in which each gesture and movement is clearly designed and sustained long enough to become embedded in the viewers’ memories. As it begins, seven identically dressed women cluster in a far corner facing an implied diagonal path; their arms are folded across their chests. The costumes by Sachi Masuda and the Stageworks contribute mightily to the piece’s affect: the women wear long, trim black skirts; black bands held across their breasts by slim cords; and black caps that completely cover their hair. They look like members of a priestly sect, but also—given the amount of muscular flesh on view— both powerful and seductive.

Muller makes shrewd use of counterpoint within the prevailing unanimity. Once the dancers—first Seiko Fujita, then Shiho Tanaka, then Caroline Kehoe, followed gradually by the others—detach themselves from the corner, they travel very little in space. Instead, they break open their opening theme’s powerful unison gestures, so that their community is fragmented in orderly ways, with everyone momentarily different from everyone else. Nor do they always embark on a new passage of movement all at once. In repetition, variation, and counterpoint, they find strength.

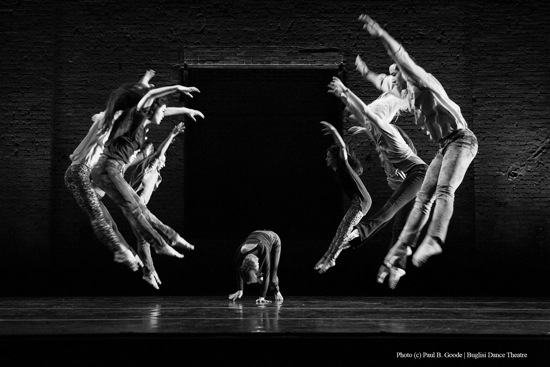

Jennifer Muller’s Whew! (L to R): Michael Tomlinson, Caroline Kehoe, and Shiho Tanaka. Photo: Carol Rosegg

Muller’s also new Whew! set to jazzy music by Peter Muller provides the up-beat closer that a traditional dance program requires. Although the dance is very lively, it feels long—perhaps because it is purposefully frenetic, with dancing itself a voluptuous stand-in for the frantic disconnectedness of contemporary life.

The dancers begin with entrances and exits, criss-crossing the stage by walking briskly, sauntering, or running, Whew!, we are reminded at times, is akin to a race and demands time-outs for a runner to bend over and catch his/her breath. In the last seconds, Michael Tomlinson plops down on the floor, mouthing the work’s title. Although there’s little indication of an actual race, certain encounters suggest a bit of competition, with gestures indicating, “Back off, will you?” and other similar sentiments, even though the performers cooperate in various intricate maneuvers.

One of the virtues of Whew! is that it gives each of the seven powerhouse dancers a moment to be seen as an individual before he or she is swept up in the momentum of the day’s “work” (dancing to beat the band). Especially compelling is Gen Hashimoto, who can go from racing around or pausing to “argue” with a colleague into dancing so silkily and easily that the choreography has the air of a garment he has just slipped into.

Elisa Monte’s Lonely Planet reveals her proficiency in terms of movement invention. There’s one quite amazing moment when the four men in the cast pair up tightly, each pair carrying two women, whose legs stick out on either side of the linked men. When the two four-person constructions turn, they briefly resemble giant bees or unidentifiable machines. Suddenly the men split apart and spread out, each holding one woman (I, for one, gasped).

Elisa Monte’s Lonely Planet. (L to R): Lisa Peluso, Justin Lynch, Mindy Lai, two dancers from a previous cast, and Clymene Baugher. Photo: Matthew Murphy

Often, however, it’s difficult to discern the relationship between the movements that Monte has designed and her themes of environmental and economic instability. Fadi Khoury is a latecomer, and although he fits into the swaying, reaching motions the others are making, he’s different in some way—perhaps, at times, a catalyst or the last survivor. It’s he who begins to press his palms against the air around him, as if he’s in a glass cage, and the others pick up on this image of isolation. Yet these people in their marble-patterned leotards with red slashes (by Keiko Voltaire) do cooperate—for example, in passing cartwheeling individuals, one by one, down a line, or, in the final moment, lifting Mindy Lai high.

When Lonely Planet begins, the eight dancers are all facing the backcloth that receives Paul Lieber’s projections. And these moving images, coupled with Clifton Taylor’s lighting, are sensational, especially at the outset, when a single glowing point explodes in a starburst of light, followed by other luminous, irregular shapes traveling in one direction. David Van Tieghem’s score provides intermittent cataclysms.

Watching this shared performance, I’m reminded all over again how difficult it can be to make choreography express the complexities of relationships if you also want it to look like vivid, eye-catching dancing. Jacqulyn Buglisi’s We Are All. . .Our Father’s Sons is set to pre-existing music by Norman Dello Joio and a composition by his son, Justin Dello Joio—an ingenious idea, although the juxtaposition is more symbolic than influential. In her duet for two impressive men, Ari Mayzick and Juan Rodriguez, Buglisi has abstracted the father-son relationship to the degree that it could it well be interpreted as other strong relationships between two men. The taller Rodriguez sometimes seems to be a leader, and he and Mayzik keep their eyes on each other much of the time—although they come and go, enabling us to see each in a solo. They also shake hands or pull against each other. But the few moments that express urgent closeness, such as Mayzick dragging himself along holding Rodriguez’s foot, evaporate. The dynamic of the piece doesn’t clearly reflect a complex, shifting relationship; it shows two interesting, allied men who are dancing together with big, impressive steps that they both know. The last moment of the duet reveals very finely what wasn’t obvious earlier: Mayzick stands alone, isolated in Jack Mehler’s lighting; he balances on one leg, the other held out low behind him. His arms are raised. Rodriguez assesses him for a moment or two, then turns and walks offstage.

Buglisi’s 2013 Butterflies and Demons is also perplexing, despite its many arresting moments. If I hadn’t learned in advance that it was inspired by human trafficking, especially that of women, I doubt if I would have guessed Buglisi’s source. Perhaps the beginning should have clued me in. Mehler has projected squares of light on the floor, imprisoning each of the eleven dancers. All are swaying, their arms up, but then red lights beam on from stage right, and all the women fall, while the men remain standing and continue to sway, eventually travelling away from the patches of light (which disappear until near the end of the piece).

These people exist in a state of panic that is accentuated by Daniel Bernard Roumain’s hectic score. They rush across the stage, fleeing some unseen enemy, and running figures appear throughout the piece, behind whatever is happening in the foreground, giving a consistency to an atmosphere that is otherwise changeable. At least twice, all the performers hasten to form a line that stretches from the front of the stage to the back; they struggle to pull free in different ways and succeed.

I can appreciate that Buglisi didn’t wish to approach her devastating topic in any literal or realistic way, but neither has she shaped Butterflies and Demons to express it forcefully. Perhaps she is saying any person can represent either aspect of this strange duality. So the piece is often exciting but also puzzling. The performers are usually in control of their dancing in the midst of unspecified disconnectedness. They encounter each other in ways that seem tender or contentious. Mayzick scrabbles after Stephanie van Dooren, and they move together in uncomfortable ways. The relationship between So Young An and Darion Smith is gentler, but full of sadness. Conditions don’t seem to get better or worse, until, just before the end, van Dooren suddenly becomes a victim, collapsed on the floor with others standing over her, staring down. As she lies there, Smith carries An across the stage. He doesn’t touch her with his hands; she balances on his shoulders as if in a mid-air swan-dive, her long black hair falling forward. It’s a beautiful image; she looks more like an angel than a burden. Perhaps she is free at last. Or maybe she’s the soul of the fallen one. Or a butterfly. I wish I knew.

Really appreciate your depth of explanation and I love reading what stands out to you from what I see at the same performance. Thank you for such a beautiful wordsmith and for sharing the questions that you are left with from the performance.