The Trisha Brown Dance Company and the Stephen Petronio Company give their New York seasons the same week.

(L to R): Nicholas Sciscione, Natalie Mackessy, Jaqlin Medlock, and Davalois Fearon in Stephen Petronio’s Strange Attractors I. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

Sitting in the Joyce Theater during the Stephen Petronio Company’s 30th Anniversary Season, the word “highflyer” suddenly pushes it way into my mind. This is not just because Petronio is ambitious and successful, but because he takes risks and succeeds when you might expect him to founder. When I dig into his invigorating, just-published memoir, Confessions of a Motion Addict, I marvel that he survived and continued to perform and choreograph through the years when he was indulging in amounts of booze, drugs, and sex that would have downed almost anyone else in the dance world.

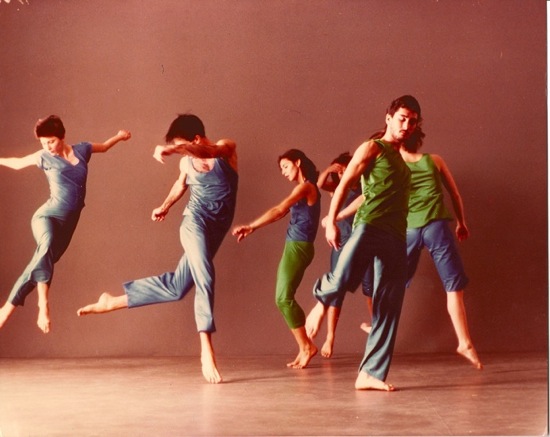

More to the point, I watch his 1999 Strange Attractors I and his new Locomotor and am amazed all over again by the movement he creates and how he patterns his dances. High flying doesn’t figure as giant, poised leaps (although these do appear), but his superb dancers often seem to be aloft in high winds, buffeted off balance, swinging their arms and legs around to maintain a semblance of equilibrium and taking off again. Yet however much they wrench their bodies around, tilt, or topple, they reveal no sense of struggle. They seem to take pleasure in what they’re doing with their bodies—not in any self-indulgent way, just making the dancing course richly through them as they cut through space.

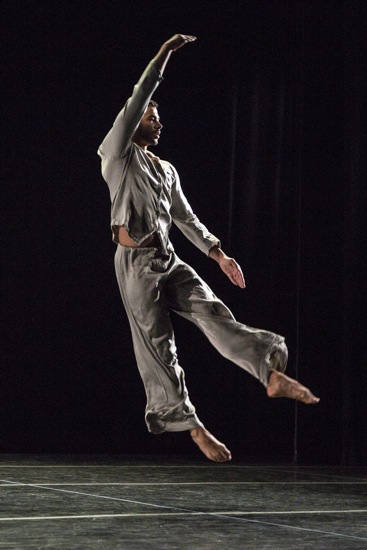

The opening solo of Strange Attractors I shows just how perversely beautiful Petronio’s movement palette can be. To luscious music for string quartet by Michael Nyman, Barrington Hinds subverts balletic maneuvers such as pirouettes and beats and all manner of jumps—canting them, blocking them, diverting the movement impulse elsewhere, and plunging them into a stew of wholly unconventional ingredients. When one of the performers—man or woman— tosses a leg into the air, the action seems effortless, as if oiling the hip joint were something everyone in the company did before going onstage. The nine dancers’ gray silk pajamas or black and gray slips (by Ghost) ripple as they pass onto the stage and off, fall into synchrony or embraces, attract and repel (sometimes at the same time). Josh D. Green and Julian De Leon, Davalois Fearon and Natalie Mackessy, Jaqlin Medlock and Nicholas Sciscione find their own ways of developing bodily conversations. The other three tirelessly wonderful dancers in Strange Attractor’s I are Joshua Tuason and Gino Grenek (now Petronio’s assistant). Medlock, marginally the smallest of the women, eats up as much space as Hinds, the marginally tallest man.

Petronio’s Locomotor, receiving its world premiere at the Joyce, explores images of past and future, forward and back, and their meeting places in the present. Narciso Rodgriguez has costumed the nine dancers (minus Grenek and plus Emily Stone and guest artist Melissa Toogood) in white leotards with sleeves and side patches gray or black (not, to my mind, very attractive, but they emphasize the point about duality).

Toogood opens Locomotor alone onstage. This past year, the onetime member of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company has been seen all over town in choreography by divers others (talk about an addiction to motion!). Petronio has profited from her alertness, from the way she inhabits pauses, and the subtle nuances with which she grooms the movement, never relinquishing its essential wildness. Establishing one element of Locomotor’s structure, she begins her long phrase on the front right half of the stage, which Tabachnik has lit for her. Minutes later, she begins the same phrase at the left rear of the area, facing back.

Once the others join in, the title is further explained. In expert changeable lighting by Ken Tabachnik and to a variegated electronic score by Michael Volpe (aka Clams Casino), the dancers run along invisible tracks as steadily as trains. However, a number of these tracks are shaped like horseshoes. For instance, three dancers, lined up out of sight in the wings, may run backward onto the stage, loop around—still close to the side of the area—make a move or two, and rush away facing the way they’re going. Or they may leap backward (not an easy maneuver) in a larger circle, even exiting backward. Unlike in Strange Attractors, the performers don’t line up at the edges of the stage, watching until deciding to join the dance; they barrel in and out, which suggests that those tracks continue out of our sight before making a U turn.

Amid the score’s flutters, flaps, crashes, roars rhythmic thudding, and sweet bits of melody, the dancers burst and ooze and slash their way into motion, now stopping dead and waiting a while, now pairing up in intimate encounters. Sometime, you see them at work through a few motionless others. Twice a dancer reappears in a red outfit, for no obvious reason. In the end, Stone is anchored while the others line up at the rear of the stage, dance forward, turn to face the other way, return to the rear, and face us again, before surging into the final moments of dancing.

There was a time when I found Petronio’s works relentless—sensual fits of movement, the goal of which was to keep on going. They still have that ongoing quality but it has gentled. He turned 58 a couple of weeks before his company’s 30th anniversary season, and, like his memoir, these performances at the Joyce look back—not so much to his large, big-hearted Italian family, but to the family of dancers he has worked with over three decades. Some have departed, some are more recent recruits, but their bodies and their sensibilities inhabit his work.

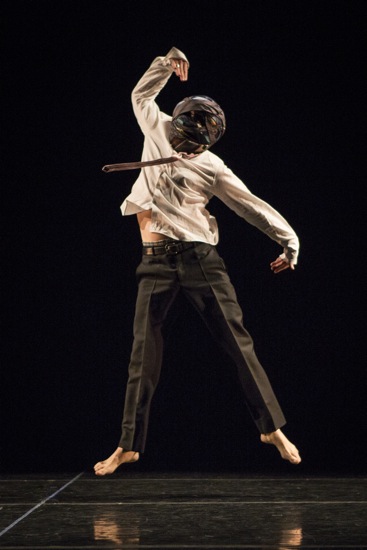

The passing of time and the reminiscences bared in his book seem to me to inform his new solo Stripped. He begins it wearing trousers with a shirt, tie, and jacket and standing in spectral light. But. . . what is wrong with him? His head looks like a gray pumpkin. To Philip Glass’s Etude No. 5, he takes off the jacket and begins to move, carefully placing a foot, changing his facing, bowing down. I later read in the program that Janine Antoni, a visual artist he has collaborated before, has designed what’s termed a “costume intervention.”

I’ll say. Petronio must be able to see a bit, and breathe, but the loose, swinging movements he develops have a certain edginess and awkwardness. He strokes his body, puts his hands over his invisible face and feels it. Is he stripping down or being born? Perhaps both. After a while, he breaches the Joyce’s “fourth wall” by unwinding a strip of cloth from his head mask and passing one end to a woman in the front row. Now he begins to spin his way out that and the two additional strands that make up the bulbous covering. He gives the beginning of the second to an invisible person offstage and the third to another on the opposite side of the stage. Oh, lovely! The last strip of cloth is abloom with bits of color. (I read that it’s made of neckties.) And finally, amid the slim fabric fences, Petronio is free, fully revealed—bald as a newborn and almost as bemused.

(L to R): Tamara Riewe, Nicholas Strafaccia, and Elena Demyanenko in Trisha Brown’s Opal Loop/Cloud Installation #72503. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

How’s this for a coincidence? The same April week that the Stephen Petronio Company opened at the Joyce, the Trisha Brown Dance Company performed one block east on 19th Street at New York Live Arts. On the program was Opal Loop/Cloud Installation #72503; made in 1980, it marked Petronio’s debut as a dancer in Brown’s company, the first man to join it. He appeared a year later in her Son of Gone Fishin’, which was also revived for the NYLA programs. You can understand where Petronio learned to make his body a terrain for detours and interruptions, along which movement nevertheless traveled like water. He took that fluidity into his own less gentle, less playful work.

Brown, now ailing and no longer at the helm of her company, left a mother lode of rich beautiful works, three of which the company’s associate artist directors, Carolyn Lucas and Diane Madden, re-staged for this season. The third is Solo Olos from Brown’s 1976 Lineup. Brown’s final work, Rogues, a duet for two men that she created in 2011 in collaboration with Lucas, plus dancers Lee Serle and Neal Beasley opens the program.

I marvel all over again at the ingenious structures that Brown devised, either to generate movement (in her earliest works) or to mold it. Rogues, with its clean, straightforward (but definitely Brownian) moves was inspired by a phrase from Brown’s Foray Forêt and danced to an excerpt from Alvin Curran’s Toss and Find, which had accompanied the earlier work. The complicated and brainy process of breaking up a long phrase and interchanging parts of it is hard to explain, but what you see are two intent men (in this case, Stuart Shugg and Nicholas Strafaccia) apparently dancing side-by-side in unison, but every now and then diverging. One might arrive at a common goal split seconds later than the other, who might in turn pause for his colleague to catch up. In the final section, accompanied by a harmonica, the dancing get faster and bigger, with more kicks and jumps, without traveling a lot around the space. The stitchery is too close for that.

One cast in Trisha Brown’s Solo Olos. (L to R): Stuart Shugg, Jamie Scott, Neal Beasley, and Cecily Campbell. Photo: Ian Douglas

If you didn’t already know that dancers are often extremely smart people, watching Solo Olos, the third work on the program, would definitely convince you of that fact. Here’s the task for (in the cast I saw) Tara Lorenzen, Megan Madorin, Shugg, and Strafaccia. They can all perform a phrase of Brown’s nicknamed “Main” forward and in retrograde. They can do the same with “Branch” and “Spill”—contrasting phrases individually constructed from descriptions that Brown wrote for the purpose. The dancers move from one to another of these three strands with ease. Beasley begins with the other cast members, then sits in the front row with a mike and calls out instructions.

So we watch a soft slew of dancing and delight in how the choreography evolves. Beasley calls out things like “Meg, spill,” “Nick, branch” “Stuart and Nick, reverse.” Sometimes he’ll ask a dancer to reverse twice or three times without a pause. As a result, two people may drop almost miraculously into unison and then later diverge. Perhaps even three fall into line. No one stops. Everyone is fiercely concentrated. In the end. . .a miracle! Beasley brings them into unison, and we cheer.

(L to R): Nick Strafaccia, Elena Demyanenko, Tamara Riewe, and Samuel Wentz in Brown’s Opal Loop/Cloud Installation #72503. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

The two works from the early 1980s are part of a series that Brown termed “Unstable Molecular Structures.” For them, she followed the example set by her 1979 Glacial Decoy in terms of collaborating with visual artists. For Opal Loop/Cloud Installation #72503, Fujiko Nakaya designed and constructed a fog machine. Like the sea fog that rolls in from the Pacific in Washington State where Brown grew up, mist rises along the back of the stage, at times foaming over the low barricades to envelop the dancers. In 1980, the narrow space of a semi-basement on Crosby street where Opal Loop appeared as a work-in-progress, four dancers had to take a long phrase of movement and loop it back to the center of the space, starting and stopping when they chose to. What you see suggests a canonic structure gone slightly berserk and occasionally resulting in sweet-tempered near collisions. What may be coincidences look like unspoken agreements (“Mind if I join you?” “Go right ahead.”).

“Opal” may refer to Brown’s iridescent, green-purple silk outfit, now worn by Elena Demyanenko. Judith Shea’s diverse costumes catch, reflect, or absorb Beverly Emmons’s magical lighting differently: Samuel Wentz wears the shiny gold unitard made for Lisa Kraus, Tamara Riewe is in billowing white, and Strafaccia in black. There’s no sound but that of water and the hiss of steam. Now fog creeps up on the performers; now it retreats to leave them in sunny clarity. Brown, growing up in the forest and near the sea, loves nature’s game of now-you-see-it-now-you-almost-don’t.

The original cast of Brown’s Son of Gone Fishin’. (L to R): Eva Karzsag, Stephen Petronio, Vicky Shick, Randy Warshaw, and (hidden) Diane Madden and Lisa Kraus. Photo: Lois Greenfield

The sea figures in Son of Gone Fishin’ too, especially as it was originally performed in front of Donald Judd’s different-sized backdrops (dark blue, light blue, and green), which moved up and down at certain intervals like occasional well-behaved waves. Shea’s costumes followed the same color scheme. But that version of the piece can’t be performed in a theater that has no fly space overhead for the backdrops to disappear into and descend from. The current cast performs without Judd’s set and in trim, shimmering gold, silver, and bronze outfits that Shea had initially designed for the piece and abandoned after Judd contributed his designs. John Torres has provided new lighting.

Brown’s Son of Gone Fishin’ in 2014. (L to R): Samuel Wentz, Jamie Scott, Tara Lorenzen, Nicholas Strafaccia, and Stuart Shugg. Photo: Ian Douglas

In Son of Gone Fishin’, as in Solo Olos, Brown had fun advancing and rewinding phrases of movement but in considerably more complex ways. Against a black backdrop, to variegated pieces of music composed for the dance by Robert Ashley, and possibly with some choreographic adjustments, the dance winds its way through the seven marvelous performers, binding and releasing them. They nudge into one another and rebound, they cling. Sometimes they arrive, as if by accident, to form a clump in one corner or another. An unstable molecular structure indeed.

What always thrills me about this dance is the way Brown took usually staid unison on a flying trip. A person off to one side may be in perfect synchrony with one quite far away, while others swirl and muddle silkily around. Now that pairing dissolves and your eye is drawn to two different dancers who’ve slipped into long-distance alignment. Two others, maybe closer, fling out a leg at the same time. The result is uncanny; it’s almost as if the dance steps had minds of their own and simply flew around, alighting where they wished, staying a while, and moving on.

Brown found climactic endings corny in the 1980s. Both Opal Loop and Gone Fishin’ just end when they end. The dancers stop, and without even a fraction of a pause, the lights go out. We don’t leave with a picture in our heads; for all we know, there’s more of the dance lurking somewhere, still in heavenly motion.

I didn’t realize that Petronio had written a memoir — thanks so much for the heads-up.

It still makes me sad to read something like this: “Brown, now ailing and no longer at the helm of her company,” but am glad to know the works are still being performed!