Ballet Preljocaj brings the French company’s Snow White to New York.

Fog swirls around a dark stage. Crashes and eerie echoes accompany it. A hand rises from a cloud bank, and figure swathed in dark garments appears and begins to walk with difficulty across the stage. It’s hard to make this person out. Ah! A crown. Royal, then. A glimpse of a bare thigh and high heels. Right. A queen. And what is she doing out in this storm alone? And yes, very far along in pregnancy.

This is how Angelin Preljocaj’s 2008 Snow White begins on the stage of the former New York State Theater at Lincoln Center. The scene introduces us to Preljocaj’s dramatically challenged version of the Grimm fairytale for the French company Ballet Preljocaj, and to the snail’s pace at which scenes progress. Why is the Queen (Gaëlle Chappaz) not at home attended by midwives and doctors? Who can say? Her dimly seen sufferings go on and on. She dies. Far from hastening to find her, a few men, among them the King (Sergi Amoros Aparicio), march slowly into sight. Slowly her spouse kneels and covers her, while groping surreptitiously around her body. Slowly the men lift her and carry her away. He stands and rocks from foot to foot for a while so that we know that what he was fumbling for was the newborn bundle he now carries: Snow White.

Then, just as you’re beginning to wonder whether you can endure over two intermissionless hours of events that unfold at this dilatory pace, Prelocaj pulls out a swift bit of theatrical magic to indicate the passing of years. Through disappearances and reappearances enabled by hanging panels, Snow White’s childhood speeds by. The King walks behind one panel, and reappears in pursuit of a very little girl (Charlotte Anoub), who skips out its other side. Father and daughter play briefly, teasingly together, before she runs behind the other panel, and emerges as a teenage princess, who’s also playful and energetic.

Snow White plays with amorous woodland dwellers. (L to R): Liam Warren, Anais Pensé, Aurélien Charrier, Nagisa Shirai, and (hidden) Céline Marié. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

The production is a rich one, both visually and aurally. The dismal or scary sound effects have been created by 79 D, while the principal choreographic passages are accompanied by excerpts from Gustav Mahler’s symphonies. Passages of silence are common. The court at which a ball is just beginning has two thrones set into a rough-textured bronze wall (set by Thierry Leproust; lighting by Patrick Riou); these rise on hidden elevators so that the King and Snow White can look down on the dancing. Jean Paul Gautier’s attire is. . .imaginative. Snow White (Nagisa Shirai) wear a white dress whose lower part consists of a sort of loose diaper and a side-positioned swag of a skirt; her flanks appear to be bare; a bunch of white feathers perches on one shoulder. The men wear shoes; the women are barefoot. They look and act like émigrés from a Breughel painting who’ve been roughed up by fashion-conscious gnomes.

They move like that too—taking bold, lusty, spraddle-legged steps, rolling to the floor, making brusque gestures. However, the twelve performers do this dancing in neat rows, evenly spaced from one another. Sometimes counterpoint occurs, but the whole design barely travels in the space, and, despite the dancers’ appealing vigor, the section seems to go on for a long time, twiddling the same, or similar, steps. Interesting those these steps can be, they proceed with little dynamic variation, as if punched out at even intervals. A dance for eight playful couples is livelier, but again, each pair is anchored in its own plot of turf. At this point, Mahler’s music is playing at a volume earsplitting enough to distort it.

Preljocaj hints at a choose-your-mate test for the Princess with a dance by three vigorous men, but this is no Rose Adagio like the one staged by Marius Petipa for his Sleeping Beauty. The potential suitors pay little attention to her, and what she may be whispering to her father is that she prefers the guy in the tight, calf-length, persimmon-colored pants with suspenders. He (Sergio Diaz) has had the sense to arrive with a red scarf as a gift. Shirai is a charming dancer, with a strong, flexible body and a rapturous way of using it. Naïve as Juliet, she’s about to meet her Romeo in a center stage kiss, but Carabosse arrives in a windstorm of sounds, attended by two nimble cats (Caroline Jaubert and Margaux Coucharrière) covered in black from the tops of their head to their toes. Oops. Not Carabosse, but Snow White’s vain, glamor-obsessed stepmother (Anna Tatarova), dressed like a dominatrix and apparently with near-magic powers to augment her malevolence. Strong men drop like flies and have to be helped up.

A giant mirror in a gold frame descends for the Queen to preen in front of, courtesy of dancing doubles (the cats have doubles too). “Who’s the fairest of them all?” Curses!!! The ensuing scenes, although still drawn out, become a lot more interesting. The heroine visits four pairs of bucolic lovers entwining on green hummocks and changing partners with abandon. She frolics with the scarf her lover gave her, and they toss it about to tease her. The Prince arrives, and the two have an ecstatic duet, full of kisses. plus unusual lifts and tanglings; they begin in silence, and eventually some of Mahler’s gorgeous music buoys them up. Shirai and Diaz are wonderful together.

In case you’d forgotten this: three of the Queen’s henchmen arrive to kill Snow White, but, although they maul her, they can’t kill her. Instead, they shoot a curious deer that appears, moving in a series of small jerks; although the creature has antlers, it also has very human breasts. It’s her heart and liver they take to the Queen as proof that Snow White is dead. Preljocaj’s wariness of using acting to convey this change of heart makes the plot a bit hard to follow.

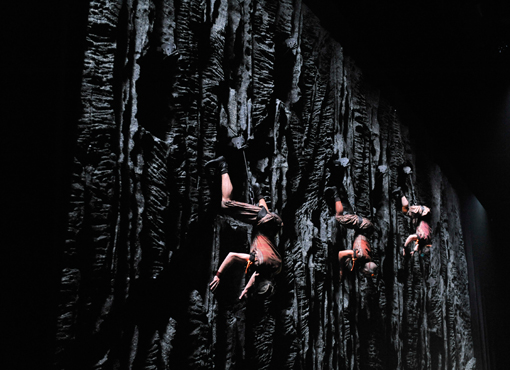

The choreographer’s most exciting idea was to give the seven miner-dwarves a rock backdrop with cave openings, out of which they emerge as aerialists—crawling down the wall like bugs, scampering up it, swinging, and turning. They’re adept at unhitching themselves from their harnesses when they need to move downstage. The music for this scene is the marvelous third movement of Mahler’s Symphony No. 1; it begins with a heavy “Frère Jacques” in a minor key and midway through morphs into a passage that makes the orchestra sound like a klezmer band.

Less appealing is the scene in which the Queen, disguised as a beggar woman, feeds the good-hearted Snow White a poisoned apple. After some byplay, the villainess jams the entire apple into the girl’s mouth and drags her around by it, until she appears to be dead. The story proceeds in enigmatic ways. When the dwarves discover their friend in a comatose state, they begin running in looping paths around the stage and dancing a bit in unison; this is one of the most spatially expansive sections of Snow White, but worry and compassion don’t figure in it. The Prince enters and sees her lying on the slanted plastic bier that the dwarves have put together. Does he hasten to her side to ascertain whether she’s dead or only asleep? No, for several seconds, he slithers to her on his belly, like the biblical serpent sneaking up on Eve.

Now comes a pas de deux more breathtakingly violent than the apple scene. It’s Preljocaj’s take on the dance-with-a-dead-body trope. The Prince slides Snow White off the panel by pulling her onto him by her ankles. There’s no limit to what he can do in the way of hauling her to her feet, shaking her, slinging her around, and clutching her tightly. It’s all that Shirai can do to maintain her rag-doll state during these maneuvers. Snow White’s awakening is set to the Adagietto from Mahler’s Fifth Symphony, and the ravishing music provides an undercurrent of beauty to what, in essence, amounts to a lengthy Heimlich maneuver. (Remember that the Grimms have Snow White being carried in a glass casket to the sorrowing Prince’s palace? And how a porter’s stumble dislodges the fatal piece of poisoned apple from her throat? This duet is Preljocaj’s creative solution to what would have been an unattractive moment.)

Snow White (Nagisa Shirai) with her amorous friends early in her adventure. Others (L to R): Anais Pensé, Liam Warren, Aurélien Charrier and Céline Marié. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

Preljocaj’s Snow White ends, as required, with a wedding party, to which many guests wear odd hats, the betrothed waltz together in new clothes, and everyone moves in slow motion through celebratory dancing. I know that in some performances of this work, Snow White’s mother descended on ropes from heaven at the point when her child appeared to have died, and the two, embraced, were momentarily lifted slightly above the stage. At the end, I’ve learned, Preljocaj’s Queen, as per Grimm, is forced to dance in red-hot shoes. If that happened on opening night, I missed it, but there was no missing the superbly svelte Tatarova being stripped of her cloak, and watching her kick and fling her legs around and wave her arms and toss her hair furiously as the curtain slowly descended. I put it down to insane rage as a result of excessive vanity. She brought it on herself.

Taking tin his Snow White was a curious experience. Because of the length, spectators were free to leave and return, especially during a long pause when we sat in the dark. Almost everything seemed to take longer than it need have (Mahler’s music, once chosen, could hardly be cut). Yet often, moments that would clarify the plot and the characters’ intentions were blurred. You couldn’t, for instance, be sure whether the assassin hired by the Queen actually cut Snow White’s throat and some magic power protected her, or whether he just drew his knife across her neck to practice (although his decision to spare her wasn’t evident).

That fog obscured more than childbirth, although it couldn’t hide the full-on fervor of the performers. The audience rewarded them and Snow White with hearty applause and cheers.