The Paul Taylor Dance Company celebrates its 60th anniversary, March 11-22.

Paul Taylor’s new Marathon Cadenzas. (L to R): Aileen Roehl, Jamie Rae Walker, Heather McGinley, Michael Trusnovec, Robert Kleinendorst, Laura Halzack, Michelle Fleet. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

Paul Taylor made his first piece of choreography 60 years ago and went on to create 139 more. Some are among the most beautiful or the funniest or the most terrifying dances you will ever see. His company is performing twenty-one of them, plus two new ones, during its two-week 60th anniversary season at Lincoln Center. You can laugh at From Sea To Shining Sea, marvel over Taylor’s wry images of society in Cloven Kingdom and Private Domain, be cast down by Dust and elated by Esplanade, feel the poignancy of wartime love affairs in Sunset.

The second and fourth programs between them offered three masterworks, one lightweight piece, and two lesser new works. In the three major ones—Airs (1978), Arden Court (1981), and Mercuric Tidings (1982)—Taylor turns the stage into a heaven on earth. No choreographer can equal him at blitheness. In these works, all set to marvelous music, the dancers skim across the floor, soar above it, sink down to it, and rise to leap again. Robust angels, they beat their feet together like wings. Their patterns convey order, but surprises lurk, like threads unraveling from a vision of perfection.

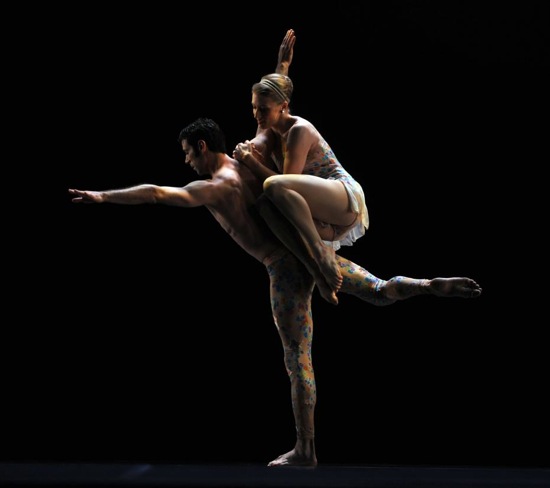

Arden Court (my favorite) is set to excerpts from five radiant symphonies by William Boyce (1711-1779). Against a projection of a huge pink cabbage rose (set by Gene Moore), Taylor deploys his cast of nine in solo forays, duets, trios, and groups that—in elusive ways—resonate with the bucolic life of those courtiers exiled to the Forest of Arden in Shakespeare’s As You Like It. One duet features a dreamer (Sean Mahoney) who strolls along, oblivious to the eager woman (Aileen Roehl) who scampers distractingly around him—climbing onto his back so that when he wants to hoist one leg, he has her weight to bear too, and scurrying in a squat under a leg that he has lifted and seems ready to hold up forever. Finally he notices her and carries her off.

If Roehl was like a bee uncertain of how to approach a flower, Apuzzo jumps about like a showy butterfly, while Erin Bugge,walks around him, eyeing him in wonder. Francisco Graziano turns the duet into a brief threesome, but Apuzzo is too pleased with himself to notice either one of them until Bugge touches him lightly. Michael Trusnovec and Laura Halzack dance more as tender equals. James Samson and George Smallwood have a fast-footed side-by-side duet (they think we’d enjoyed it so much that they pop back onstage and perform it twice as rapidly). In between these are robust or quiet group passages; an athletic piece for the men, bristling with arms and legs, and a lovely slow-motion men’s canon in place; a gentle sextet for three couples. There’s a little surprise at the end of the canon; the dancers standing in a chain, lifting their clasped hands high, but Mahoney is upside down, and they hold his legs. To every rose a worm, and a joker at every solemn occasion.

Airs is also set to ravishing music, in this case excerpts from several of George Friedrich Handel’s Concerti Grossi, opus 3, and, as usual, Taylor varies his approach; sometimes his steps hew closely to a musical phrase, sometimes they ride over it, sometimes they dive in and out of it. Airs also features skimming runs, with the dancers’ arms swinging; all manner of leaps, jumps, and skips; little, low side hops with the legs beating together in the air; and quiet moments when people sit on the floor to watch others, or engage in affectionate partnerships. Halzack—full and fluent in everything she does, has a fine solo. Robert Kleinendorst bounces through a jaunty hornpipe of sorts, with startlingly fast jumps, while Roehl throws herself around as fast and accurately as she can.

The music seems faster than I remember. I worry about Bugge in her duet with Trusnovec; he lets her down almost to the floor and sweeps her high again at warp speed. The best thing about this duet is that we get to see it twice—once fast and then in smooth slow motion that calms its excitement and brings out its sweetness. Airs has always seemed to me to have one section too many, but all are gorgeous.

Laura Halzack and Robert Kleinendorst looking mercurial in Paul Taylor’s Mercuric Tidings. Photo: Tom Caravaglia.

Mercuric Tidings propels excerpts from Franz Schubert’s first and second symphonies. And in that rich musical atmosphere, the dancers’ feet are as winged as Mercury’s, and the tidings that this messenger of the gods brings are of beauty and happiness. Such spins, such flying leaps! Every entrance of dancers is in itself news, and they come and go all the time. Tableaux form and dissolve. This is a piece in which Taylor creates motifs and brings them back in different ways at the end—shortened and transformed. Trusnovec and Halzack are the king and queen of this swift-footed, limber gathering, but you notice the pairing of Heather McGinley and Christina Lynch Markham and the trio made up of three smaller women, Roehl, Bugge, and Kristi Tornga. (Lynch Markham and Tornga joined the company in 2013 and are fine additions to it). Five more men (Kleinendorst, Mahoney, Graciano, Apuzzo, and Smallwood) complicate the revels and partner the women. (Graciano drawns my eyes; he has become a more vibrant dancer than he was a year or two ago—alert, tuned-up, a pleasure to watch.)

Taylor often inserts little mysteries into his pieces—not spooky ones, just oddities like ones you might see any day. For instance, Michelle Fleet sometimes joins Roehl, Bugge, and Tornga, but often she’s on her own while they are dancing together. Is she their leader or a mild-mannered rebel? Certainly, at one point, she looks like a lady-in-waiting introducing her charges to Trusnovec and Halzack.

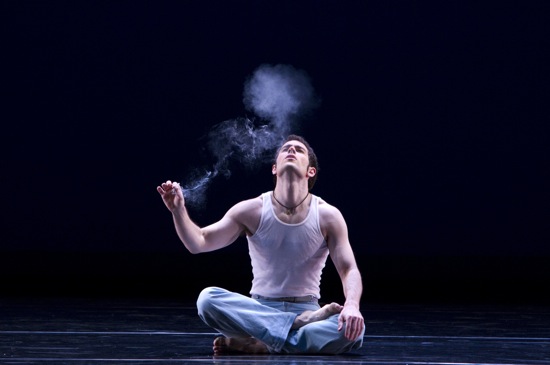

I’ll skip over A Field of Grass. Its marijuana jokes (grass—get it?) amuse the audience, with Kleinendorst pulling on a joint and leaving a trail of smoke as he dances, and six other mildly stoned folks in bell bottoms and other 1970s attire having a ball. For me, the problem is Harry Nilsson’s recorded songs. (Remember his “Spaceman” and “Hey mother earth, won’t you bring me back down safely to the sea?”)? They’re good tunes, but, they all have a lazy, swingy rhythm, and as enjoyable as it is to see the terrific Taylor dancers get loose and dreamy, I tire of the scene sooner than I’d like to.

Taylor’s two newest works, American Dreamer and Marathon Cadenzas, remind me a little of his House of Joy (although they’re “dancier” than it was). Like that whorehouse romp, the premieres seem cut short, as if the choreographer tired of them and wanted to bring them to a speedy conclusion. And, compared to the majority of his works, they seem skimpy. Their principal value seems to me that they show what his beloved company members can do in the way of bringing characters or stereotypes to life.

The title American Dreamer refers to Stephen Foster, and his are the familiar old songs to which Taylor has set his dance. These are wonderfully sung in a recording of that name by Thomas Hampson, who can roughen his voice for a song like “My Wife is a Most Knowing Woman” or, for “Beautiful Dreamer,” lift it into a caressing higher register that makes him sound like a tenor from several generations ago.

In Santo Loquasto’s design, the stage, somewhat confusingly, looks like a stage, with a portable barre, a stylized painted backdrop that suggests a draped curtain, and some chairs and wardrobe trunks off to the side. From on top of the trunks, the dancers grab bonnets and hats and a prop or two, such as the fan with which Fleet sashays around to make Michael Apuzzo crazy. Taylor’s take on the goings on is slightly wry (oh, those old, sweet songs). Roehl wears a sunbonnet to be ” romanced by Graciano (who enters whistling) as “Molly! Do You Love Me?” begins. Michael Novak uses a hand to pantomime his palpitating heart to McGinley.

Among the activities: parading around and getting into a group for a photo op (a “flashbulb” goes off). The cleverest pattern is a suddenly materializing square dance for trios (there are twelve dancers in the cast) set to an instrumental medley. The most amusing numbers are the duet for Bugge as the termagant of a wife and Kleinendorst as her hapless husband, and “Beautiful Dreamer.” In the latter, Sean Mahoney plays the role of the ardent, constantly disappointed suitor, while one by one, Fleet, Jamie Rae Walker, and Roehl, wearing diaphanous white negligees, rise from a heap to sleepwalk. The onstage barre turns out to be a fence a dancer can get caught on. Over and over, Mahoney confronts a woman, his arms open, and she —also reaching out—walks, unseeing right past him. If he hurls himself to the floor in adoration, she steps over him. Mahoney is marvelous at showing the transit from devotion to dejection to renewed hope (“alas! . . .Oh, what the hell, here comes another one”).

Marathon Cadenzas is slightly more puzzling in terms of what it suggests and what it actually is. It’s possible that the title alludes to the possibilities that may arise if you fuse a dance marathon, like those of the 1930s, with a dance contest, in which competitors show off their specialties. In dance marathons during the Depression, couples in search of much-needed prize money, danced for hours on end in hopes of being the last pair standing. The music, by Raymond Scott (1908-1994) has an edge of weirdness (some of his tunes were adapted for Warner Brothers’ cartoon shorts). Given these elements and the sleazy behavior of Mahoney—white suit, hair slicked back, starting pistol—as the only one in charge, I expected one of Taylor’s darker visions, but that didn’t fully materialize.

Paul Taylor’s Marathon Cadenzas. (L to R): James Samson, Christina Lynch Markham, Francisco Graciano. Michael Novak, Michelle Fleet, Heather McGinley, Jamie Rae Walker, Laura Halzack, Aileen Roehl. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

Loquasto, as might be expected, came up with a revealing array of costumes not all relating to the 1930s, but conveying all walks of life. McGinley, for instance, wears a silky evening gown, while Fleet shows off a checked overall, and Kleinendorst sports a shabby sweat jacket. Summoned by Mahoney’s pistol, some of them show off their specialties. Fleet works her hips with uncanny mastery. Samson and Novak, costumed as sailors in summer whites, perform a hornpipe of sorts. Kleinendorst launches himself into a buck and wing. To vaguely Middle Eastern music, Halzack moves in a serpentine manner (with the small blondes Walker and Roehl as backup), which moves Mahoney to bury his face in her neck. McGinley and Trusnovec lead the others forward in a stately couple dance; the joke (will everyone get it?) is that the steps are drawn from Renaissance and Baroque court dance (step onto one toe and sink down, bringing the other flexed foot to nestle at stepping foot’s ankle).

Marathon Cadenzas (L to R): Michael Novak, Heather McGinley, Robert Kleinendorst, Francisco Graciano, Jamie Rae Walker, Christina Lynch Markham, Michael Trusnovec, James Samson, Laura Halzack, Sean Mahoney. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

Finally the marathon proper starts, but not as the usuall pair. Instead, the twelve dancers, paired or not, start slogging around in a circle, getting tireder and tireder, while James F. Ingalls dims the lights. It’s painful to watch people fall and get up again or be hauled to their feet by friends. But, for some unknown reason, Mahoney stops everything and, while the others watch and quake, goads Trusnovec into a solo stint. Back to the competition idea. By now, Trusnovec is exhausted, but he dances (magnificently) a brave, falling-apart solo, and he and McGinley can leave (winners, I think). Mahoney, his job done, escorts Halzack away. In the end, a single body remains onstage. Sleeping? Dead?

Perhaps Taylor, committed to creating one or two new dances a year to keep his repertory fresh, was making a statement about dancers’ sacrifices and the punishing event that a rehearsal can be and the unquenchable hope that everything will turn out all right and that everyone will be a winner. Mahoney could well have represented a rehearsal director from hell, or a taskmaster hovering in the brain of a choreographer who has a company and a reputation to maintain, pinching him hard if he allows his creativity to sleep for even a minute.

Deborah, I certainly agree with you that Taylor’s new “American Dreamer” is a “skimpy” work. It certainly is pleasant enough, but there was little in it that would make me want to see it again. But I did enjoy the sleepwalkers section: I saw it as both a gentle parody of, and homage to, the glorious pas de deux between the Sleepwalker and the Poet in Balanchine’s “Night Shadow”. I wonder if you, and others saw it this way also.