Sarah Michelson premieres 4 at the Whitney Museum, January 24-February 2, 2014.

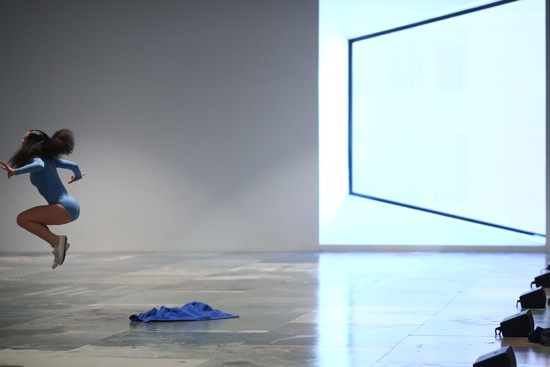

Rachel Berman in Sarah Michelson’s 4 at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Photograph © Paula Court

Watching three of the four related works that Sarah Michelson presented between 2011 and 2014 is like entering an immaculate world of passion abstracted. And by passion, I don’t mean that of one person for another; Michelson seems more deeply involved in the devotion, the single-minded burning zeal demonstrated by saints and holy men, such as Jesus Christ, and the passion of the dancer, who binds body, mind, and spirit to a single strenuous ordeal. A remark by George Balanchine clung to her 2012 Devotion Study #1– The American Dancer: “Superficial Europeans are accustomed to say that American artists have no ‘soul.’ This is wrong. America has its own spirit—cold, crystalline, luminous, hard as light…Good American dancers can express clean emotion in a manner that might almost be termed angelic. By angelic I mean the quality supposedly enjoyed by the angels, who, when they relate a tragic situation, do not themselves suffer.” In some hard-to-define sense, Michelson’s new 4 is the most pared down of the series, the most reduced to its elusive essence, the most crystalline. The four principal dancers print rigorous individual patterns on the world they inhabit; rarely in unison, almost never touching, they share a common movement language but follow separate paths—often alone in the space.

In each of the three works, the performing space was re-designed and occupied in particular ways. The 2011 Devotion, took place in The Kitchen, a black-box theater. Devotion Study #1—The American Dancer, took over the fourth-floor gallery of the Whitney Museum of American Art as part of the museum’s Biennial. The third, a sketch for a work that Michelson didn’t develop further (and that I didn’t see), was performed at the Museum of Modern Art. For 4, she returned to the Whitney’s fourth floor.

The gallery is immense, with a single huge trapezoidal window set in an angled alcove in one wall. For 4, the floor is covered with an artful array of panels bearing paint slashes and puddles of paint in mostly earth tones. Michelson, Jay Sanders, and Greta Hartenstein, who did the job, matched the twenty-one shades with those secreted in the floor under the Masonite. The dancers might be on an arid planet, with curious scars and traces of former vegetation. From our chairs, set in two rows opposite the elevators, we can’t see Michelson and Whitney curator Jay Sanders, who sit in a windowed booth in the wall behind us, engaging in intermittent dialogue by Richard Maxwell about the arts, religion, and more. And few of us can see James Tyson, who sits at a computer, recording numbers that Michelson lists from time to time (interspersed with the command “change”) and inputting them to make the numerals on the five luminous, green “score-keepers” clustered on one wall advance or freeze.

The installments of Michelson’s multi-part oeuvre echo one another in various ways. In Devotion, for instance, two dancers at one point wore black-and white costumes and red socks, referencing the color scheme of Twyla Tharp’s In The Upper Room, and they danced to a portion of Philip Glass’s exalted score for that work. Tharp too thought of dancers as heroes—a heavenly cohort of sorts (her title refers to a New Testament gathering of the apostles). Toward the end of Michelson’s 4, Glass’s music again bursts out—more powerful than the distant-sounding songs and bits of noise that have been emerging sporadically from tiny speakers at the feet of first-row spectators. Dancers identified as Adam and Eve appeared at the Kitchen. They appear again, well into 4, in the persons of John Hoobyar and Madeline Wilcox. But this time, they do not touch, beyond the handshake they offer each other before entering the action, nor do they unite in any other way beyond sharing the space and the same moves at different times.

Rachel Berman in Sarah Michelson’s 4 at the Whitney; James Tyson at the laptop.

Photograph © Paula Court

The piece begins just after (or when) Rachel Berman and Nicole Mannarino meet near the audience and hug. The former is billed as Narrator and the two together as Holy Spirit. Do not imagine that we spectators immediately say to ourselves “of course!” What we do see are two members of the same species. Berman is costumed in a shiny pale blue leotard, Mannarino in a darker blue one. Both wear white sneakers and have the front part of their hair lacquered into a semi-helmet, while the rest frizzes out around their head like tail feathers.

Berman is the first to enter the arena. She sheds a jacket and takes her place in the center of the room, facing the elevators and the three museum guards on duty (whom Michelson begins by thanking, so we won’t be annoyed by their presence). Berman bends over and gradually pulses her way into straight-up jumps. She jumps and jumps and jumps, then drops into a deep, wide-legged position, holds it for seconds, and jumps again. After that, she somersaults with absolute precision along a path. She doesn’t exit, just retreats to one of the stations in the aisles between spectators where more jackets and water in designer bottles wait. Then she enters the space again and repeats, with variants, her prescribed sequence. She can land in a deep lunge; she can kick out her legs in the air; she can jerk her fingers; she can switch her knees from side to side. What she cannot do is fly.

We will see her and Mannarino and (later) Hoobyar and Wilcox jump many times and in many ways, including while turning. A few movements have emigrated from Devotion, notably one in which a dancer lands in a wide, deep lunge related to ballet’s fourth position, her back bent, her hands reaching forward. In this pose, she looks almost like a gunslinger on a wild-west street, except that her spread fingers hold no weapons. Your hip joints ache for her. Every now and then one of the performers races to a new spot or marches back toward the coats and the water. Sometimes, they fling the coats off as they enter, and, at certain times Michelson, garbed like a frowsy stage manager, picks up and redistributes the jackets—some brown, some blue, some hooded, all very interestingly cut (credit Charlotte and Jessica Sims).

The dancers are valiant workers in a space far too large for them to patrol. At best, they leave their trails. We have to turn our heads to sight them at the far ends of the gallery. They also come and go. Now there is one person in the space, now two, eventually four. Now a performer presses into a corner, now she or he labors near the window. Now the gallery is brightly lit (lighting design by Michelson and Zack) Tinkleman; now all the lamps go out, and the dancers appear in dimness or what comes through the window (lighting by God, and extremely beautiful). I understand why 4 had to be performed at 2 P.M.

Nicole Mannarino with coats (James Tyson, foreground) in Sarah Michelson’s 4 at the Whitney. Photograph © Paula Court

Although the spoken conversation has an informal air, it is all scripted; to make that clear, Michelson and Sanders repeat the opening portion of text twice. It’s not possible to take in what they (and occasionally Tyson) are saying while watching these heroic dancers at their ordeals. Words emerge and trickle away. The speakers mention the title of Proust’s great work as it was first translated into English, In Remembrance of Things Past, and its later version, In Search of Past Time. But why, I’m not sure. Nor do I connect Michelson’s “You said Milton; I was thinking Shelley” with what I am seeing or what I’m pondering about what I am seeing. I also worry like a dog at such statements as Sanders saying that there are only two kinds of love: love of self and love of God (I can’t recall whether Maxwell’s text is quoting someone else). No love of others? Hmm. Michelson’s program “thanks” occupies a two-columned page of dense and, yes, loving acknowledgements of all who helped bring the work into being.

As a dance/installation lasting over an hour and a half, 4 is the kind of work that puts some people’s backs up. It’s uncompromising, sharp as glass, resilient only within strict confines (those pristine recurring somersaults look as if the wheel has just been invented and improved upon). It also demands a lot of its audience. There is a formidable amount of repetition and a limited vocabulary of movement that’s performed with maximum strength and clarity. When a dancer jumps up, lands on one leg with the other stuck out, and holds the position, the tiniest wobble (of which there are few) has the force of an off-course error.

I’m intrigued by the surprises or the rare occurrences. Out of nowhere, Tyson appears, clad in black tights and bare-chested. With staccato prances on straight legs, he traces the perimeter of the space, following every right-angled turn into and out of an alcove. Far off to one side, your eye is caught by Wilcox; feet planted, knees bent, she loops her hips into slow figure-8s. At one time or another each performer executes a certain action once only; one task involves bending low to touch the floor with one hand, as if acknowledging the earth; for the other, the dancer stands close to the audience, on tiptoe, eyes closed, arms spread. A hope for flight?

Rachel Berman jumps, James Tyson foreground, in Sarah Michelson’s 4 at the Whitney. . Photograph © Paula Court

From time to time, one of the elevator doors opens, and before it can close again, we see a few inquisitive faces; the guard stationed in front of it would discourage any entrances. This, like every detail of 4 must be orchestrated—must mean something in the larger picture we yearn to grasp.

There are a few costume changes; once Berman appears bare-breasted and in black tights—like, and unlike, Tyson. Twice, coats are dumped on the back of a bent over dancer (once only, as I recall, by Michelson). Tyson appears toward the end wearing a horse’s head (the same open-mouthed, wild-eyed one he wore in Michelson’s previous Whitney work), and suddenly, in one aisle, the other four—those terrific, undaunted athletes—hug, and he wraps his skinny arms around the cluster. Perhaps this signals that the work is over, but it’s not.

4 seems to increase in density and speed during its last minutes, then thins out and slows in its overall rhythm. Michelson begins a long monologue about a “she.” Did she say at one point that “you don’t need to understand her?” She could be speaking of dance, of a dancer, of herself, of, I don’t know, inspiration. Her need to say all this is moving in its intensity, infuriating in its opacity. I catch a sentence or fragment here and there, “Are you human or are you wraith?” “She won’t give you anything but shape.” “You won’t do anything that allows her to be real.”

So, yes, I find 4 occasionally irritating, often mystifying, but also fascinating, original, and, at moments, beautiful and moving. Among the spectators around me, no one sighs heavily or shifts around on the cushioned, but hardly comfortable benches. Michelson leaves nothing to chance—not a hair, not a hesitation, not a change of direction or a costume or a quality of light. You can dislike her work or argue about it in your head, but you can trust that—for better or for worse— you’re seeing and hearing what she wants you to see and hear, and that she knows what that is. She accepts the risks and plows ahead.

Thank you so much for your insight into this new and very different performance. For me, the title gave it meaning. And of course, seeing how difficult this piece was for the dancers. They truly are devoted, in many ways, to the expressive nature of dance.

The New York Times should hire you! In fact, I think I’ll suggest it to the editors. You clearly understand the art form much better than their reviewer.