Rennie Harris Pure Movement re-visits the 1990s

Rennie Harris’s all-male P-Funk. (L to R): Kyle Clark, Ryan Cliett, Phil S. Cuttino, Raphael Xavier (hidden), Shafeek Westbrook, Brandyn S. Harris, Joshua Culbreath. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

When Lorenzo (Rennie) Harris lists himself in the program for his company’s Joyce season as “Dr. Rennie Harris,” you can forgive him for flaunting his two honorary doctorates—the most recent one from Columbia College in May of last year. Through his teaching and his choreography, he has raised the public’s awareness of hip-hop as an art form while still acknowledging its birth on the crime-ridden streets where he grew up and started dancing.

More than any other choreographer interested in vernacular forms, he has refined the style and its variants through formal strategies, without sacrificing its grit, its rivalries, and the rough fellowship that sustains its practitioners. The hugely gifted members of Rennie Harris Pure Movement cover ground more freely than street-corner dancers, they join in unison, and integrate their more amazing b-boying moves into choreographed scenes depicting rivalry, warfare, or plain high spirits. Amith Chandrashakar’s lighting gives these additional theatrical sheen.

The mix of poetry, sophisticated word play, and slangy raunchiness that rolls through Harris’s masterwork, Rome and Jewels (think Romeo and Juliet) is evident on another level in the brilliant monologue that D. Sabela Grimes delivers to begin the program. Just watching him in a constricted patch of light repeatedly breathing himself into a taller, more imposing guy and then shrinking down to normalcy is a theatrical adventure. Singing, rapping, joking, sinuously adjusting his slim body, rippling an arm, he can gently mock ballet by placing his feet in first position. He can get tough or deliver poetry, like the line from the song “Kill the Boy” that goes, “I walk around with a bullet on my tongue.”

For the company’s Joyce season, Harris has chosen to present only works from the 1990s. P-Funk and March of the Antmen date from 1992, the year he founded his group. He made Students of the Asphalt Jungle in 1995, Continuum and Rome and Jewels in 1997. All of them in one way or another refer to street culture and neighborhood bonding, tackling violence and the need to avoid or renounce it. Their concerted rhythms, their astonishing acrobatic feats, and their assertiveness can convey mutual intent, rivalry, and warfare. These elements cross gender conventions too; Dinita Clark, Katia Cruz, Mai Le Ho Johnson, and Mariah Tlili are part of the group.

Harris honors hip-hop history—assimilating, re-shaping, and re-contextualizing b-boying, popping, locking, gliding, the wave, and more. The dancers can appear sinuous to the point of bonelessness, dissect their moves into robotic jerks, drop into splits, and then muscle-up to execute aerial back-flips or spin on their heads. Balanced on one hand, they can twist their legs around until they look like a living version of a knot you’d never learn in boy scout training.

Romeo and Juliet could have been made to order for Harris’s style and themes. What are the play’s young Montagues and Capulets but rival gangs battling for turf? West Side Story made that even clearer. Harris gives us the Montagues as the “Hip Hop Family,” while the Capulets are the “B-Boy Family.” You remember the former for their skiddy, springy footwork and the latter for their gravity-daring athletics. Street talk, lines from West Side Story’s “Cool,” and Shakespeare’s dialogue mingle audaciously. Sometimes Will S. gets a bit of a makeover, as in narrator/MC Ozzie Jones’s reference to “star-crossed homies.” The terrific Rodney Mason, who won a Bessie in 2001 for his performance as Rome, makes the hero evolve from a supple, primate-like creature struggling to speak to a member of a tough-talking, thieving community where a man can say of a woman, “she had dumps like a truck.” Like Shakespeare’s Romeo, however, he is finally ennobled and made articulate through love. The bard’s lines come trippingly on his tongue when he woos the invisible Jewels (“Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?”) It was a masterly decision on Harris’s part to have his Juliet a non-present presence.

The men of P-Funk. (L to R): Brandyn S. Harris, Raphael Xavier, Kyle Clark (in air), Ryan Cliett, Phil S. Cuttino, Shafeek West in P-Funk. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

I believe that Rome and Jewels has been edited for the Joyce. That may be why the characters aren’t clearly etched sooner. When I saw the piece at Jacob’s Pillow in 2000, I knew almost immediately which dancers were Rome and his buddies, and I understood that the MC was a Capulet part of the time. In the performance I saw at the Joyce, it took me a while to sort this out (Joel Martinez as a pretty serious Mercutio, Grimes as Ben V, and Raphael Xavier as Tibault), which somewhat weakened the drama. But there’s no mistaking who’s against whom in the battle. Rome’s gang—Brandyn S. Harris (who looks a lot like his dad), Dinita Clark, Kyle Clark, and Ryan Cliett—dress in black. James Colter, Joshua Culbreath, Maria Tlili, and Shafeek Westbrook fight for the Caps sporting red pants.

The battle and its outcome are elegantly organized, but thoroughly street-style. Mercutio, as is traditional, takes a while to die. The wounded Tibault gets brutally finished off by Rome and friends, and Rome kicks the body. While others dance, he pulls up his conscience with Hamlet’s line “O what a rogue and peasant slave am I,” but he doesn’t commits lovelorn suicide. He is shot by Jones, who takes from his arm the watch that Rome had stolen from him.

March of the Antmen also shows a death, and it’s preceded by another speech by Grimes. One line sticks in the memory: “You can’t outrun the Four Horsemen in a Lexus.” For sure. In the end, the men who go from lying and twitching to marching in time with the fierce music (Darrin Ross and Grisha Coleman have re-written Dru Minyard’s original score). In the end, they pick up their fallen comrade (D. Clark, I think) and carry her away.

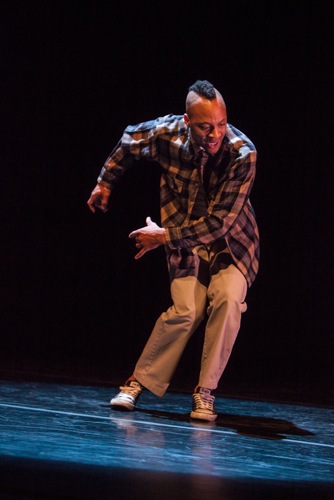

Shafeek Westbrook launches a flip in P-Funk. Watching (L to R): Raphael Xavier (hidden), Kyle Clark, Phil S. Cuttino, Joshua Culbreath, Ryan Cliett, Brandyn S. Harris. Photo: Yi Chun Wu

Continuum and Students of the Asphalt Jungle approach dancing in different ways, but both bring soloists to the fore. You remember them in flashes. In Continuum, for instance, D. Clark all but Russianizes the style with her moves in a deep squat. Culbreath, a virtuosic athlete, rises onto the toes of his sneakers. Students of the Asphalt Jungle approaches virtuosity through virtue. Martin Luther King’s voice speaks out, while the men, bare-chested and wearing white pants, enter and embrace in pairs. When the percussion in Ross’s music (re-written from the original score by Goodmen) starts, they jump themselves into a slant and vault straight up.

In this choreographed non-competitive competition, everyone gets a chance to take the center of the circle, and you can admire their differences—from tall, lithe, fast-footed Kyle Clark to the much smaller, tougher Colter. From Phil S. Cuttino Jr., who started b-boying in performance at the age of four, to Mai Le Ho Johnson, a French woman who fell in love with hip-hop at twelve. Now is the time for some of the guys to get down on their hands and knees so that Westbrook can race into a flip over them. He’s a marvel of agility, elasticity, and finesse (he wowed the So You Think You Can Dance judges in 2012). To see him balance on one hand and cantilever his body into a position nearly parallel to the floor is thrilling.

By the end of the evening, you can see Harris’s choreography setting the hip-hop culture on another plane. The dancers make their bodies into weapons that slice the air; their feet skate on treacherous turf; they fly like hopeful angels.

I’m so proud of my son, he is brilliant. I love his talent, heart & soul I get him. “you go boy” keep doing what you do. You are proud, yet, Humble, love you