David Roussève/REALITY appears at Peak Performances, February 6-9.

It’s a story you might read in the newspaper almost any day. An orphaned boy in an inner-city ghetto is sodomized by a foster father and bullied by the classmates he tries to emulate. The kid—fragile, good at heart, not too savvy, and gay—gets understanding from the school therapist, Miss Thelma, to whom he’s sent to for acting up, and he receives stern, but loving and encouraging messages from his grandfather via Skype. An older boy he admires texts him an invitation to dinner in a restaurant. He’s ecstatic. Afterward, his idol rapes him in a dark alley. For once, he stands up to his attacker. A brick is thrown. He dies.

But this is not a news item that it hurts you to read. It’s a dance drama called Stardust that David Roussève made for his Los Angeles-based company, David Roussève/REALITY. As in his Saudade, seen here in 2009 (also presented by Montclair State University’s Peak Performances), the specific actions in Stardust’s plot are dislocated and transformed.

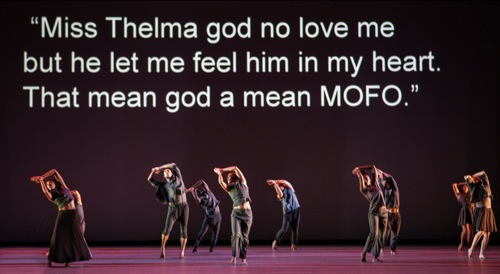

This time, the choreographer has used two very up-to-date devices both to distance and intensify the tragedy. His teen-aged protagonist never appears on the stage of the Alexander Kasser Theater; his thoughts form on the cyclorama in big white letters. His longing for friends, his love of velvety old Nat King Cole songs, his tender feelings toward his digital wind-up hamster, his excitement over Van Gogh’s “The Starry Night” (seen on a class museum trip), his hope that a benign God is looking after him, his pain, and his loneliness—all these are relayed by text messages he hopes someone will read. Is God checking his e-mail?

The projected words are interspersed with Cari Ann Shim Sham’s Disney-sweet projections of huge butterflies, clouds, mountains, and the starry skies that Junior would like to fly into. “Nobody my facebook friend,” he writes, but “I no can never cry.” His lonely misspellings and brave twitterspeak are both comical and heartbreaking. But he does, a couple of times, receive messages from his grandfather via Skype (or “Skite,” as the old man calls it). Each time, a giant, homemade-looking mock-up of an iPhone is wheeled onstage in a momentary dimming of Christopher Kuhl’s lighting; on it appears Roussève’s face. Wherever he is, the reception is poor. Looking weather-beaten and speaking in a crackly voice, he lectures Junior lovingly about being strong and good and trustful of God.

You know from the outset where this will get the boy, just as you know what is going to happen when he walks happily out of the restaurant with the big fellow he’s so honored to be with. No surprises in this story.

Foreground (L to R): Charisse Skye Aguirre, Kevin Williamson, and Michel Kouakou in Stardust. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

The people we do see onstage dance. And their dancing reflects various changes in Junior’s moods and desires. As does the music. King Cole singing “Nature Boy” and other songs bespeak the boy’s essential sweetness, while d. Sabela grimes’s music and sound design conjure up the urban neighborhood’s violence and raucous games. In the beginning, the ten dancers (seven of them past or present students in UCLA’s World Arts and Cultures department, where Roussève is a professor) are spread out across the stage, making quiet, unison gestures that expand gradually in scale and travel out into space.

Some of the dancing that happens as the story begins to unroll puzzles me. Roussève means it, I assume, to reflect the buoyant, optimistic aspect of Junior’s thinking, but it looks generic—big swirling turns and springs into the air and drops to the floor create a homogenous texture; nothing looks as gently quirky and jolting as Junior’s mind. However, as Stardust goes on, the movement becomes tougher or more playful or more affectionate, as well as rhythmically interesting—relevant to the neighborhood as well as to the protagonist’s state of mind. Familiar gestures are worked up into motifs: performers grab their crotches, inflate their chests, and spread their arms (“you talkin’ to me?” or “don’t look at me!”).

(L to R) Nguyên Nguyên, Leanne Iacovetta, Jasmine Jawato, Kevin Williamson, Taisha Paggett, and Michel Kouakou at play in Stardust. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

Emily Beattie whispers something to Taisha Paggett, and it starts them giggling and shrieking with laughter out of all proportion to what may have been said. Paggett and Beattie, plus Nguyên Nguyên and Nehara Kalev dance, while others watch. Clarisse Skye Aguirre, Leanne Iacovetta, and Kevin Le imitate one another’s steps. Aguirre, Kevin Williamson, and Michel Kouakou bolt into the foreground, while seven others form a chain behind them, making slow, mournful gestures. Jasmine Jawato takes on Kouakou. At times, they are the friends Junior would like them to be. A rainbow assemblage. Ghetto angels.

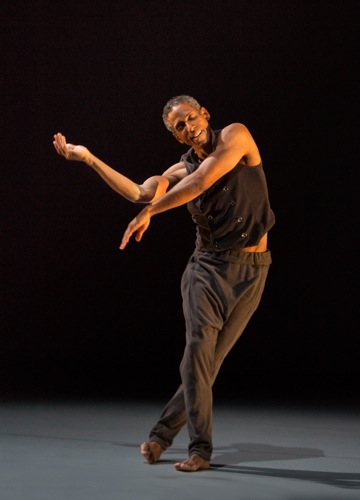

Roussève himself appears onstage unexpectedly, standing in one spot to perform a meditation tinged with anguish—his arms fondling and pushing away air, his torso sinuous. Some time after that, Junior writes, “My grandpa dies.” Johnny Mathis sings “Ave Maria.”

All of the performers are vivid, and some are remarkable— Beattie and Aguirre, for instance, in tumultuous solitary outbursts. Near the end Paggett dances through a cluster of data: projected text recounting the rape; Grandpa’s voice exorting, “Junior, hear me in your dreams!” Ella Fitzgerald singing, “Reach for tomorrow; today belongs to the past;” and the Beatitudes from the Bible’s Book of Matthew (“Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall see God. . . .”) Her beautifully nuanced performance anchors them all.

Roussève treads a very fine line in Stardust between gritty tragedy and fairytale pathos—never quite falling one way or soaring another. Like the fictional life it honors.