The Dance on Camera Festival 2014 presents Chantal Akerman’s film about Tanztheater Wuppertal and Fabrice Herrault’s about Rudolf Nureyev.

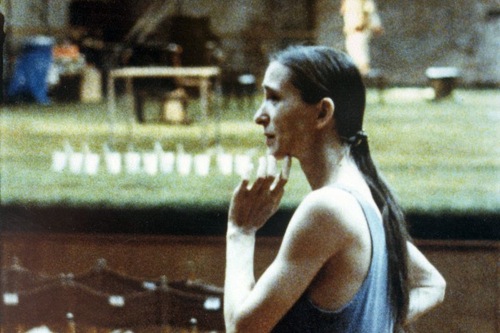

Chantal Akerman’s One Day Pina Asked. . . (1985, in French with subtitles), was advertised by the Dance on Camera Festival as a “rare retrospective showing.” It was shot during a five-week tour by Pina Bausch’s Tanztheater Wuppertal. What the fine director documents—and that’s hardly the right word—are primarily moments from Bausch’s works, shot and edited into a kind of collage; there aren’t a lot of long shots. The director was clearly more interested in the interactions of performers in performance than in the remarkable environments created for the works. We see little of Bausch herself. As the film begins, she’s rehearsing the group in an outside theater, while a voice-over (Akerman’s?) introduces her. Later, as she watches her dancers strut in a line, making coy little gestures over and over to a jaunty piece of music, she smiles a bit and her hands sometimes stir in small responses.

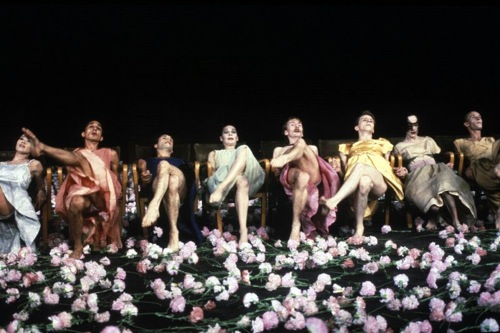

These are the marvelous performers we first came to admire when Tanztheater Wuppertal first appeared at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. Few are identified along the way (that would possibly have stopped the momentum of the film, since many short sequences elide into one another. Most of these are from Nelken (Carnations) and Waltzer (both from1982), plus Komm Tanz Mit Mir (Come Dance with Me) (1977). There’s also a scene from Kontakthof (1978) that makes your skin crawl. Nazareth Panadero is surrounded by men who adjust her and play with her body; they crowd in to flick her nose, stick a finger in her ear, rub her stomach, push her shoulder. She just stands there, sad and hurting, as they keep repeating and intensifying their attacks. The camera is close enough to seem like one of them, but it shows us her pain.

Members of Tanztheater Wuppertal in Nelken (Carnations). Dominique Mercy in pink, Lutz Forster in yellow, Kyomi Ichida far left. Courtesy Icarus Films

Repetition is a crucial ingredient in Bausch’s work, whether it escalates or just repeats exactly until it becomes terrifying. Over and over, Josephine Ann Endicott tries to get passing men to dance with her. “Komm tanz mit mir,” she begs them, ever so coyly, reaching out to them, trailing them. Ever more desperately, she repeats her invitation. Eventually they encircle her in a not very friendly way; she loves the attention. Dominique Mercy, wearing a dress (as do all the men in Nelken at certain times) point, has a fit of temper at the watchful camera. “Do you want to see something?” he yells into the camera and moves away display a balletic feat, each time getting red in the face and angrier and shouting louder at a public that apparently craves virtuosity and isn’t getting enough.

Akerman zeroes in on quieter moments too. In one, Lutz Forster shows his response to Bausch’s request that all the dancers perform something they were proud of. He learned enough sign language to stand before the audience and gesture to a classic recording of “The Man I Love,” mouthing the words. A beautiful vignette.

One Day Pina Asked. . . also shows the dancers in various backstage dressing room, often shot through open doors, as they silently mop sweat, powder their faces, and are helped into new costumes.

At the end of the film, Bausch is asked how she sees her future, and the camera waits while she thinks. And thinks. Finally she says, “I don’t know, because I don’t know what I wish for myself.” She thinks about than, then ventures, “strength, love.”

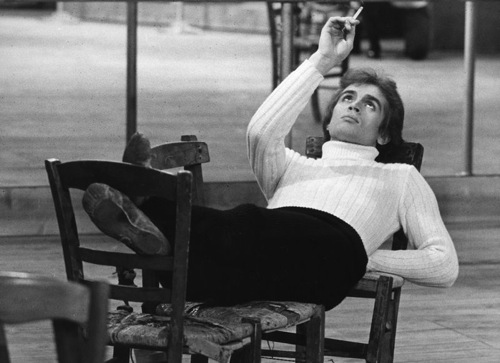

Fabrice Herrault’s La Passion Noureev is aptly titled. Not only does its subject, Rudolf Nureyev, have a passion for dancing that surpasses all his other loves; Herrault’s film is like a love letter to the dead dancer and to his fans. I understand that there were lines waiting to get in to the showings. Historians can be grateful for all the film excerpts from ballets—some of them surely rare—that Herrault dredged up. No moving image—no matter how blurry, no matter how grainy—was too poor in quality to be included. Over and over Nureyev leaps, pirouettes, whips into high-speed chains of turns, vaults across the stage. Handsome tigerish, he seeks the perfect line, the perfect position. Every clip is labeled (a bonus). Swan Lake in Vienna, 1966; in New York, 1972; Corsaire and Laurencia in Leningrad, 1958; Sleeping Beauty in Paris, 1961. At some point along the line, someone says, “He learned to operate what he knows.”

Herrault includes stills, a rehearsal scene with an unnamed ballerina (maybe Noelle Pontois), and very interesting staged class in which Nureyev and his lover, the great Danish dancer Erick Bruhn, do exercises at the barre together, facing now toward, now away from each other, and then begin moving across the floor. Bruhn has a certain elegant ease; Nureyev’s dancing looks born of struggle, and sometimes he loses the sense of flow. Yet part of what makes him charismatic is the impression he gives that control and perfect positions have emerged only after some inner beast has been wrestled into partial submission. We follow his defection, his partnership with Margot Fonteyn, his branching out (he’s terrific in a clip from Roland Petit’s Le Jeune Homme et La Mort). In interviews, he says that his life is all about moving from one theater to another and dancing, dancing, dancing. Even in dreams, he’s thinking how to make the greatest effect.

We can’t get enough of this great dancer, Herrault thinks. Certainly he can’t, and at the end, he creates a numbing whirlwind of film clips: a paean to entrechats, grand jetés, pirouettes, sweeping attitude turns, and more. It’s Nureyev as unstoppable force, as if ceasing to do this thing that he knew how to do so well would be the end of him.