New York’s Dance on Camera Festival 2014 premieres two documentaries: Miss Hill: Making Dance Matter and Paul Taylor: Creative Domain.

We’re old hands at documentary films about major figures in the art world. That is, we pretty much know what to expect: we’ll glimpse the artist at work and hear him or her talk about it—alive or in grainy film clips. Various soul mates, friends, colleagues, former students, and critics will be shown sitting in becoming light, uttering encomiums, dredging up memories, and recounting stories about the subject. An invisible narrator may guide the flow of images. The camera will come in close on paintings, take a virtual walk around sculptures. If the subject is a dancer, filmed excerpts of her in action on stage or in the classroom are required. A little sweat is good. If it’s a pianist, he’ll be practicing in his living room, adjusting his tie in the dressing room, and performing in a hushed concert hall.

When I read over what I’ve just written, it sounds snarky; I don’t mean it to be. In the first place, each director of a documentary mixes these and other ingredients in his or her own way—emphasizing one, eliminating another, setting up a rhythm. Second, we hunger for insights into the careers of artists we admire, especially those in our own field. We recognize their value to history, although we do well to be suspicious of documentarians’ accuracy. What complex process may be simplified or speeded up for theatrical or financial reasons? Or presented out of context?

This year, as in its previous 41 years, the Dance on Camera Festival (co-presented by Dance Films Association and the Film Society of Lincoln Center) showed a mix of documentaries, narratives, and experimental films. Between the last day of January, 2013, and February 4, 2014, dance buffs could take in around twenty film showings and several panels, talks, and discussions. (I had to forgo the big screen, the snacks, and the conversations for a laptop screen or a medium-sized tv monitor.)

Four documentaries shown during the festival reveal subtly different perspectives, rhythms, and camera work. Greg Vander Veer’s Miss Hill: Making Dance Matter (2014), Kate Geis’s Paul Taylor: Creative Domain (2013), Chantal Ackerman’s One Day Pina Asked. . .(1985), and Fabrice Herrault’s La Passion Noureev (2013).

Martha Hill (far left) leading her technique class, New York University Camp at Lake Sebago, Sloatsburg, N.Y., 1931. Photograph Courtesy of the Martha Hill Archives.

Vander Veer was obviously entranced by his subject, Martha Hill, a bold, outspoken teacher and administrator, who with Mary Jo Shelley, founded the Bennington Festival in 1934, taught at New York University, and served as head of Juilliard’s Dance Division from its inception in 1951 to her semi- retirement in 1985, when she turned 85 (she was the department’s emeritus artistic director until her death at 94). Who could not fall for film clips of the tall, loose-boned young dancer leading her students over the lawns of Bennington College or, years later, ruling over Juilliard, always in tailored attire, her hair in its famous side-of-the-head bun.

It’s made clear in the film that, although she danced in Martha Graham’s first company, Hill knew she would never be a major dancer and sought another role. What that woman managed to do, especially in term of putting modern dance on the map and getting food into dancers’s stomachs! As countless former associates, admirers, students, and observers recall in the film, she brought the leading modern-dance choreographers of the day (Doris Humphrey, Charles Weidman, Martha Graham, and Hanya Holm) to spend summer weeks teaching and making new works at Bennington; (here they are in snapshots, wearing their hot-weather clothes and hanging out). She lured Graham, José Limón, Antony Tudor, Anna Sokolow, and others to the Juilliard faculty, and generously created within Juilliard a semi-professional company (open via audition) to give Humphrey an outlet for her choreography.

Drama and conflict enter Vander Veer’s film in the mid 1960s. It appears that Juilliard may be forced to drop its Dance Department in the course of its move from Claremont Avenue to its new Lincoln Center site; Lincoln Kirstein wants all the available studios for the New York City Ballet and its school. When former New York City Ballet dancer Heather Watts says that Kirstein thought he could have Martha Hill for lunch (meaning with her on the menu), he was out of luck. A compromise was reached, and, in one of the most vivid stories revealing Hill’s get-up-and-go, Dennis Nahat (at the time a Juilliard student, tells of finding Hill in her old office on a Saturday night packing up her papers; at her request, he helped her load the boxes into cabs. The two sailed past the guards into the not quite finished new building. When Hill saw two dance studios she liked, she wrote “Juilliard” on sheets of paper and taped them to the doors; she found a smaller space, set up the boxes to form a desk, and labeled it Juilliard Dance office.

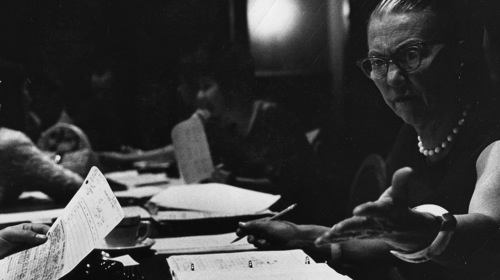

Martha Hill watching Donald McKayle work with Juilliard dancersl; to her right: Wlliam Louther(?). On the floor (L to R): Dudley Williams, Mabel Robinson, and Pina Bausch, 1959/60. Photo courtesy of the Martha Hill Archives

Not all those who speak about Hill are as insightful as, say, her biographer Janet Mansfield Soares (ex-Juilliard); current faculty member Risa Steinberg; or onetime Juilliard student and member of Limón’s company, Daniel Lewis. And there are over twenty people to tell of Hill’s guts and charm and wise decisions. Sometimes you could wish to have fewer say more.

I have quibbles about missing identifications of people, locales,and dates. For instance, in a photo of three student dancers being coached by Donald McKayle, while Hill watches, only one of the three, Bausch, is identified. Twice Nora Kaye’s face appears unidentified and in dramatic close-up during the scenes focusing on Tudor; you’d think she was just another gifted Juilliard student instead of a Ballet Theatre star he often featured in his ballets.

Nonetheless Miss Hill: Making Dance Matter is a treasure trove of images and revealing stories, lovingly assembled. It made me miss her all over again.

Kate Geis’s Paul Taylor documentary, like Miss Hill, received its world premiere at the Dance Film Festival. Its focus and rhythm are very different. And Paul Taylor: Creative Domain also differs in approach from Matthew Diamond’s 1998 Dancemaker. Taylor, remarkably, allowed Geis into his studio from the moment he began work on his Three Dubious Memories in 2010. The atmosphere and pacing of the film is relaxed but never boring.

No admiring outsiders appear to laud Taylor; a few of the dancers and others associated with the work talk about his process. Taylor himself talks to the camera while sitting at his desk chewing gum (sometimes a cigarette appears at the same time) or tosses producer-director Geis a remark—witty, rueful, matter-of-fact, as he walks from the dance floor to the reel-to-reel tape deck that he still favors. He shows his notes; he confesses to once stealing some moves from Tudor’s Dark Elegies. He’s frank about this work; it may not turn out to be one he likes (someone in the film mentions that the only work Taylor says turned out the way he expected it to was Esplanade.) This whole documentary business might be a game he’s playing with some interest.

Geis begins with the first meeting at which the company sits on the floor and Taylor reveals his plans for the work. He got the idea from the film Rashomon, so at the heart of the new dance is the fact that people remember the same event differently. For all his doubts about what’s to come in the way of choreography, he knows that he’s using some unusual music by Peter Elyakim Taussig that he heard and liked, and he describes the roles the dancers are to play—outlines that he doesn’t fill in. They set to work.

Paul Taylor works with Amy Young, watched by director Kate Geis and her film crew. Photo: Tom Hurwitz

Taylor is extremely skinny now and slightly bent over, but he’s out on the floor, getting down on one knee to demonstrate a move, showing Robert Kleinendorst or Sean Mahoney how to hold Amy Young, indicating a turn to James Sansom, who’s the leader of a dancing chorus. Talking, nudging, asking the dancers to try this or that, Taylor is enmeshed in creating the dance; when he sits down again, Andy LeBeau, former company member, now his assistant, may step in to solve a problem or query a move. The dancers give intelligently and unstintingly. “Watch ’em and love ’em,” Taylor tells the camera.

The film thickens and quickens gradually. Santo Loquasto tries costume ideas. The composer comes to a run-through in the studio and grins in pleasure as he watches. The dancers don makeup and costumes for the piece’s premiere in Richardson, Texas, which we see snatches of. Taylor thinks something is still missing, but what?

Next thing you know, we’re back in the studio—dancers on the floor, Taylor at the tape machine. He’s telling them what he knows about the next dance they’re about to begin. The film quickens memories in anyone who has ever danced professionally. “Yes,” we say to ourselves, “that’s how it felt, that’s how we coped; remember that kind of sweat?” For the uninitiated, the interplay of labor and inspiration may come as a surprise. A dance gets hammered out, made to fit, and polished to beauty like a shoe made by a master cobbler.

Thanks