The Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater premieres Aszure Barton’s Lift at City Center.

(L to R): Jacqueline Green, Linda Celeste Sims, Kelly Robotham, and Belen Pereyra of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater in Aszure Barton’s Lift. Photo: Paul Kolnik

Any choreographer invited to make a piece for the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater must come to the first rehearsal with both elation and trepidation. The Ailey dancers are like racehorses—sleek, swift, eager, ablaze with temperament. What can you feed them? How do you groom them? Are you up to the job?

Robert Battle, who took over as artistic director of AAADC in 2011, is the first “outsider” to lead the company. His predecessor, Judith Jamison, had danced in it for 15 years and headed it for 21. Battle has made some smart decisions—such as acquiring Ohad Naharin’s Opus 16 and Paul Taylor’s Arden Court and commissioning new work from Rennie Harris and Kyle Abraham.

The current City Center season shows off the dancers in Wayne McGregor’s Chroma and Bill T. Jones’s D-Man in the Waters (Part I); the commissioned premieres are Ronald K. Brown’s Four Corners and Aszure Barton’s Lift. So far, Lift is the only one I’ve been able to see.

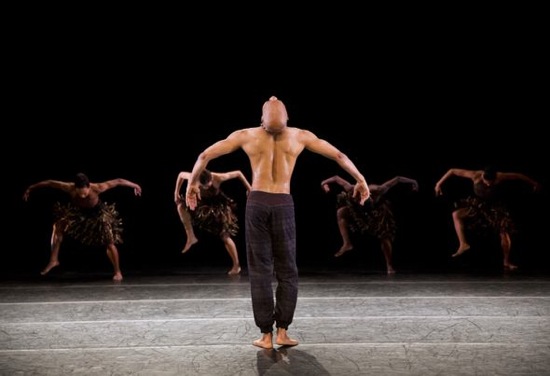

Barton puzzles me. I found the first small works of hers that I saw bold, original, and fascinating, wasn’t crazy about her One of Three for American Ballet Theatre, but enjoyed how she employed Juilliard students in her wild-west Happy Little Things (Waiting on a Gruff Cloud of Wanting). What surprises me about her Lift is a kind of inconsistency—of trails pondered but not taken. There are dramatic lighting effects by Burke Brown (including smoke), a dozen or so men, and six women. The men are bare-chested above their dark gray pants, except for slim gold necklaces. The women wear dresses by Fritz Masten that pair halter tops with feathery layered skirts.

We seem to have stumbled into a ritual from some undetermined African country. At the outset, tall powerful Jamar Roberts is flanked by Renaldo Gardner and Daniel Harder. Close together, facing front, they hunker down into the emphatic rhythms in Curtis Macdonald’s score. When they turn away from us, they face the other men, ranged along the dark back of the stage. In lines, all retreat and advance, shaking their shoulders, stepping hard, sometimes jumping straight up. At one point, only Roberts and his two companions are lit, but—and this is revealing—the two are now Antonio Douthit-Boyd and Kirven Douthit-Boyd. Revealing because I wouldn’t have noticed the change had I not been told of it. So is Barton making a point about replacement and cycles of life? If so, what with all the great-looking, identically garbed men forming patterns and showing their virility and dedication in unison steps, who focuses on individual faces?

Most of the steps have a tribal look to them (Roberts is wonderful at all of them—supple, strong, focused, charismatic). The performers move into wide-legged, bent-kneed stances; they bring their hips and shoulders into play. And, over and over, they slap their thighs. They also, however, lift their straight legs high, toes pointed, and turn in balletic attitudes—as if steps from some other works in the Ailey repertory have sneaked in. Sometimes, an interesting group pattern will emerge—such as the three men doing their thing amid— and semi-screened by—lines of others doing different steps. But Barton seems committed to having a lot of people onstage most of the time. The texture of the piece is thick and unchanging, the stage often filled with evenly spaced-out dancers.

Occasionally people open their mouths in silent yells; at least once, the yells are audible. In a moment of prominence, Ghrai deVore and Marcus Jarrell Willis laugh out loud while they dance. The principal variations in tone appear in a solo for Matthew Rushing and a duet for Linda Celeste Sims and Roberts. Both these vignettes come out of the blue and remain enigmatic. Rushing, now a guest artist with the company, as well as a rehearsal director, enters the action like a visiting shaman, first backed by the women. Or maybe he’s our host. Rippling his arms, strutting a bit, he takes over the stage. Who he is and why another man writhes introspectively in the background during his solo are mysteries. Rushing is, of course, marvelous—weaving every step that the choreographer gives him into a fluent, eloquent statement. He, too, turns his back to the audience, and trudges toward the dark rear of the stage, shoulders shuddering.

Since Roberts performs the duet with this beautiful woman who just dropped out of the female ensemble, should we assume that he is entering a new phase in his life, or a new role in this busy society? What’s intriguing and original about the duet is also what’s weird about it. As the two travel together across the front of the stage, Sims pushes her head into Roberts’ midriff; his spine curves as he shrinks away from the impact, then expands again. As she travels toward the wings—he following— the process repeats and varies. She could be kissing his open, receptive chest or inhaling his manliness or sucking out his soul. Who can be sure in this strangely constructed world?

Rennie Harris’s Home, which opened the December 7th matinee, offers a different vision of community. The lively, beautifully designed piece premiered on December 1, 2011, World AIDs Day and the 22nd anniversary of Ailey’s death, but you might not guess from looking at the work that the solo figure represents a man isolated from the group because of the virus. What you see is a vibrant bunch of people—14 counting the wonderfully expressive Harder, who is exiled but, in the end, returns to the fold. He could be anyone who is seen as “different” but then embraced despite that.

In the meantime, the dancers come and go—now in hordes, now in threesomes, in quartets, two at a time. Harris keeps the stage atmosphere as changeable as that of a good party, except that everyone is expert at the steps drawn from hip-hop, and in tune with everyone else. Harris doesn’t present any of the moves as grandstanding and weaves everything into foot-lively, body-shaking, going-somewhere patterns. This choreographed community maintains its identity and reveals the dancers who make it up as the bright, gifted individuals that they are.

The program concluded with Ailey’s iconic Revelations; I regret that, for once, I couldn’t stay to see unfamiliar dancers in roles I practically know by heart.

Loved your conclusion to your rich description of Lift: “She could be kissing his open, receptive chest or inhaling his manliness or sucking out his soul. Who can be sure in this strangely constructed world?” apt questions following what I garnered was interesting to watch though inconclusive and even frustrating. Writing in your columns is so admirable as in this example. THANK YOU, always Judith