Anneke Hansen Dance performs a new work at the Martha Graham Studio.

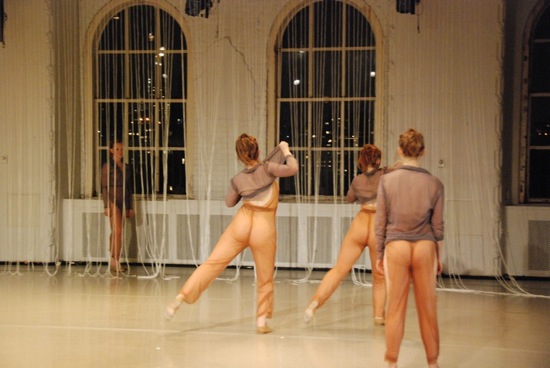

Anneke Hansen’s she is not a comfortable thing. Foreground: Hansen. Behind her; Alice MacDonald. Rear: Ashley Handel (L) and Emily Moore. Photo: S.E. Bicknell

I pondered the title of Anneke Hansen’s new, full-evening dance before I saw the piece and again as I was walking home from what is now the Martha Graham Studio Theater. she is not a comfortable thing. What can that mean? That being a woman sometimes means not being comfortable with your body? That the way some people think of women may make a woman feel uncomfortable? That women have a lot not to be comfortable about? But thing, how does one read that?

Hansen herself is strong, resilient, and beautiful. Her choreography creates an interplay between big, powerful movements that can take to her into the air or compel her to roll on the floor and small, particular gestures and shifts of weight. But athletic as it can be, her dancing is very sensuous, and she crafts it with precision.

For she is not a comfortable thing, Hansen is joined by Ashley Handel, Alice MacDonald, and Emily Moore—colleagues who are attuned to her lushly physical way of moving. The piece —let me be clear—is not about dancers throwing themselves around. The women do a lot of observing one another, of thinking, of looking into the distance as if searching for answers. Nor is there a “story” that must be followed. If you like, the work is about four women in a particular space at a particular time, who move together with a common, if enigmatic purpose.

Behind “curtain”: Alice MacDonald. (L to R): Anneke Hansen, Ashley Handel, Emily Moore. Photo: Bryan Fox

When the piece begins, the four are standing with their backs to the audience, at the opposite long wall of the studio. They stare out of Westbeth’s 11th-floor windows at the lit-up city night. (Those familiar with what was formerly the Merce Cunningham Dance Company’s studio will immediately get the picture). There is a curtain very near them that separates them from us and continues along the wall to our left. This barrier (designed by Jian Jung) is made up of ceiling-to-floor white ropes, so although it could suggest jail bars, it is supple and permeable. In fact, there are two separate instances of a women gathering a number of strands together and standing with the bundle draped over her shoulder. Holly Ko’s lighting sometimes throws the performers’ shadows on the white walls.

Nathan Koci’s score, played by him on the piano and on electronic equipment, contains chunks of silence, when we hear only the dancers’ feet. Sometimes his contributions are spare and evocative. For instance, after Handel has made her first forays out from behind the “curtain” and back again, we hear a thudding, plus high sounds, and careful piano chords. But Koci can also raise the energy, density, and volume, as well as making use of “You Ain’t Alone” by the Alabama Shakes and “After You’ve Gone” by Turner Layton/Henry Creamer.

The women’s identical costumes (constructed by Baille Younkman) are light-brown, sleeveless, partially backless jumpsuits with gray, long-sleeved tops over them. Beige jazz shoes complete the elegant outfits. You see at once that the clothing is made from a light-weight, semi-transparent fabric akin to organdy (the once favored material for little girls’ party dresses), but it takes a while longer to realize that the women are naked beneath their outfits. So a social, possibly political issue enters the picture: who is uncomfortable now, and why? What is the difference between these women whose bodies are visible under their loose clothing, and dancers who wear sleek unitards that reveal every contour and muscle, but mask the body’s texture and markings?

Anneke Hansen’s she is not a comfortable thing. (L to R): Alice MacDonald, Ashley Handel, Anneke Hansen, Emily Moore. Photo: S.E. Bicknell

It’s impossible not to be aware, at least some of the time, of the dancers’ veiled nakedness, which becomes even less veiled when they remove the over-blouses. When they lie curled up on their sides with their haunches toward us, you feel that Hansen is making a statement, just as she is when the women pull their shirts up to cover their faces briefly, then discard them entirely. They are acknowledging their femaleness, for sure, and, along the way, their power, their skill, and their endurance, for they do a great deal of strenuous dancing, whether in unison or in counterpoint or in solos. A trace of jazz mobilizes their hips. We hear their breathing, see their sweat.

They also show us their camaraderie, as well as their ability to stand apart from one another and consider things. When a voice singing a drowned-sounding blues gives way to a loud, constant vibration, Hansen goes to MacDonald, who has been crawling over the other two women, hoists her up, and struggles to carry her to a new spot. Handel moves to help Hansen. If one woman collapses, another may be there to catch her.

Often while watching them, I find myself thinking of them as challenged and challenging, alert to something we can’t see, but which is going on around them. What makes one or more of them retreat behind the curtain from time to time? Hansen occasionally looks into the distance, as if she has heard a voice and is trying to assimilate what is being said.

Perhaps that voice is what has been calling this thoughtful young choreographer to explore movement deeply, sensitively, and with fresh perspectives.

Sounds fantastic! Hope to see it in the flesh some day. Wonderful and very relevant subject, particularly in today’s day and age. Intriguing.. Congratulations Anneke! Keep on inspiring the dance community and beyond! Look forward to seeing you here or there. x L