The Lar Lubovitch Dance Company celebrates its 45th anniversary.

Permit me to be fanciful about why Lar Lubovitch chose to devote the first half of the first of two programs his company is presenting at the Joyce to three duets (not a decision I would have recommended). However, Lubovitch founded the group that bears his name 45 years ago, and ever since, he has been showing us how much—often intemperately— he is amorous of lush, sensuous movement. Compressed into a duet, his choreography announces his love affair with dancing the minute two performers appear onstage.

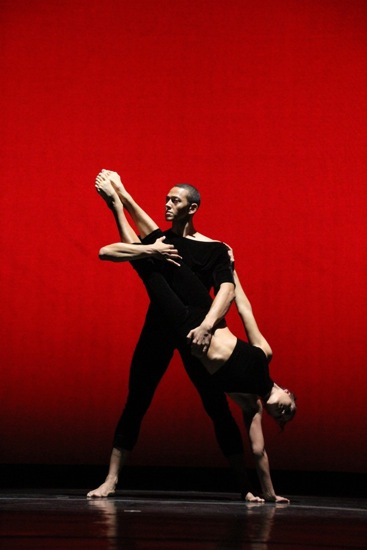

The men who perform the profoundly expressive duet from Lubovitch’s 1986 Concerto Six Twenty-Two (in this case, Attila Joey Csiki and Tobin Del Cuore) enter from opposite sides of the stage, walking slowly toward each other to the adagio movement of Mozart’s great clarinet concerto, K.622. What they feel for each other is muted, restrained, but hauntingly clear. The first image in the new Vez is of a man (Clifton Brown) holding his partner (Nicole Corea) upside down at a knife-straight slant, against a glowing red opening in the black curtains behind them. Even if a singer and guitarist weren’t stationed onstage, you’d guess that this relationship is a hot one and that tango will flirt its way into the choreography. When The Time Before the Time After (1971) begins, Katarzyna Skarpetowska and Reed Luplau are locked in an embrace. Her first move is to wilt within his grasp, slide down, let her head fall back, and reach up to him; his first move is to push her away. That’s when Igor Stravinsky’s Concertino for String Quartet gets rough too. Nearly every anguished complication the pair attempts cries out, “I hate you, but I can’t live without you.”

Attila Joey Csiki (L) and Tobin Del Cuore in Lar Lubovitch’s Concerto Six Twenty-Two. Photo: Phyllis McCabe

Within the confines of his chosen atmospheres, Lubovitch finds many eloquent ways of making movement reveal the charged relationships. Virtuosity serves to define both elation and struggle. Concerto Six Twenty-Two, choreographed in the thick of the AIDs crisis, reveals a tender male friendship that is both reticent and deep. The men walk forward, sculpting a pretzel-shaped vow with their curving arms. The next thing you know, Csiki is sitting on Del Cuore’s shoulder as if he’d gotten there in a single exultant bound; when Csiki, kneeling, stretches out one leg like a slanted bed, Del Cuore reclines against it. Each man dances for the other—Del Cuore devouring space with his long legs, Csiki more precise, more erect in his posture, both of them excellent.

Vez is a remake of Lubovitch’s 1989 Fandango. Instead of being performed to Ravel’s ultra-famous Bolero, the reconfigured duet is accompanied by a commissioned score by Randall Woolf. Recorded elements subtly reinforce the live music, performed by singer Mellissa Hughes and guitarist Gyan Riley (for instance, more hands than theirs clap rhythms). Jack Mehler’s lighting dramatizes the partnership of Brown and Corea, both of whom wear black velvet attire (her costume all but backless).

Even before Brown places his hand meaningfully on his partner’s nearest breast, the two have shown us what unusual connections they can slide their bodies into. He picks her up and folds her into a bundle; he bends deeply backward on a slant and she holds him just before he hits the floor by grasping his neck. He lies down, and she walks on him. The two dancers give the choreography a quiet intensity that’s more gripping than more overt expressions of passion would be; several times they nearly kiss, but decide to titillate each other and the audience by prolonging their foreplay.

Prolong is a key word in another sense. The love that Lubovitch has for rich movement occasionally verges on being out of control. He’s an expert and disciplined dancemaker, especially when it comes to working within prescribed limits (say, those of a Broadway show). But when he’s his only boss, he sometimes can’t stop. He’s like an attentive lover who becomes so extravagant with bouquets and boxes of chocolates that the choreography begins to feel surfeited.

Reed Luplau holds Katerzyna Skarpetowska in Lar Lubovitch’s The Time Before the Time After. Photo: Steven Schreiber

This is true, too, of The Time Before the Time After, even though, in this case, the constant fluctuation between rage and devotion expresses the stuck nature of this pair’s relationship. The duet is full of discomfort and downright nastiness. Luplau grabs Skarpetowska by the hair. He raises a hand, beckons to her, and points toward the floor; she kneels at his feet. Yet, suddenly they may be leaping together, side by side. Their anger erupts into real battles, but is also formalized into the striving, pressured dancing that both perform with bone-deep feeling. The day-in-their-life winds back to that embrace. This time Luplau keeps Skarpetowska in his arms.

It’s a joy to come back from intermission to one of Lubovitch’s finest works, Men’s Stories. I first saw the piece in 2000 in that eerily beautiful former synagogue, the Angel Orensanz Center, then again in 2011 at the Baryshnikov Arts Center. Fortunately, the Joyce, even though it’s a proscenium set-up, is fairly intimate. Despite the swirling patterns formed by the nine superb performers, Lubovitch wants you to see these men as individuals with their own agendas and needs. Anthony Bocconi, Jonathan E. Alsberry, Csiki, and Luplau all express themselves in solos (Alsberry’s is especially fascinating and not a little weird). Some of them join in duets.

The dance’s subtitle, A Concerto in Ruins, is illuminating. Scott Marshall’s “audio collage” contains all manner of music, speech, and noises—both violent and sweet—but persisting deep within the score, and sometimes surfacing full-voiced, is Beethoven’s fifth and last piano concerto, the “Emperor.” The composer wrote it in Vienna in 1809, when Napoleon’s army was entering the city, shattering it with artillery fire and explosions.

Lar Lubovitch’s Men’s Stories. Foreground (L to R): Oliver Greene-Cramer, Attila Joey Csiki, Anthony Bocconi, Milan Misko, Clifton Brown. At back: John Michael Schert (L), Reed Luplau, and (top) Jonathan E. Alsberry. Missing: Brian McGinnis. Photo: Steven Schreiber

The nine man in their nearly all-black attire by Ann Hould Ward (trousers, shirts, vests, tailcoats, and shoes) show us their solidarity in unison dance, stare at us as if we’re their mirror, bow, shake imaginary dice, and make courtly gestures (“no, after you”). Brian McGinnis and Oliver Greene Cramer seal a more than comradely duet with a handshake. But all is not love and brotherhood. Amid the tide of dancing, little tensions surface. Brown makes haughty assertions. The men crowd in on Alsberry to force him offstage.

In service to culture more recent than the 19th century, Marshall’s composition treats Beethoven’s masterwork roughly—braiding into it or squelching it with what sounds like a jazz singer in a bottle, a lame 1950s (?) sex-education talk between a father and son, a poem, a carousel’s music box, a soprano warbling “Ciribiribin,” as well as explicitly abrasive noises such as broken glass, voices yelling, gunfire. During the last part of Men’s Stories, the dancers remove their coats and roll up their sleeves to fight one another fiercely. It’s amazing how only nine men (Milan Misko and Michael Schert round out the cast), plus Clifton Taylor’s brilliant atmospheric lighting, can convey the messy ferocity of a battlefield. Lubovitch also, briefly, presses the dancers into the kinds of sculptural groupings that represent soldiers struggling toward victory, dying, slogging on.

Beethoven’s concerto—which has continued throughout Men’s Stories, whether heard or not—finally comes to its triumphant end. The men put their coats back on and are resting, when—surprise!— Alsberry appears, manipulating a marionette that’s about two feet tall. Carefully, man and the mannequin walk to various of the dancers, and Alsberry makes his puppet shake a hand, bow, pat a shoulder. This is the first time that I’ve thought of this big-headed little figure in the black suit as Beethoven—come to say, “Thanks, gentlemen. I understand.”

Note: The company’s Program B begins at the Joyce on October 15 and runs through the 20th.

Thanks, Deborah, for being an eyewitness while I am so far away.