William Forsythe brings his 2011 Sider to the Brooklyn Academy of Music.

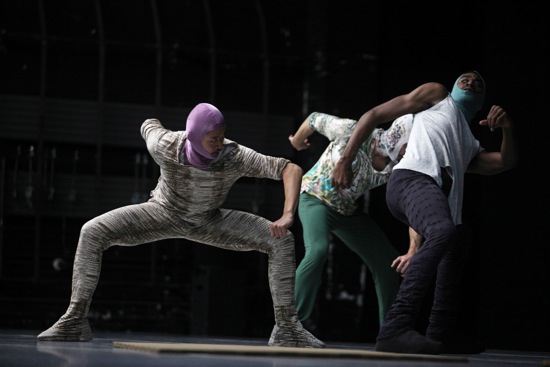

William Forsythe’s Sider. (L to R): Yasutake Shimaji, Cyril Baldy, Josh Johnson. Photo: Julieta Cervantes

When you watch a recent work by William Forsythe, you may find yourself responding to it on two levels. Sitting in the Brooklyn Academy of Music to watch his 2011 Sider (part of BAM’s 2013 Next Wave Festival), you take in what the dancers are doing (say moving large rectangles of corrugated cardboard around), and you hear a pounding, atmospheric score by Thom Willems. But you also think about what you don’t see or hear—notably the elements that shape what the dancers (co-choreographers all) are doing. In other words, you may be fascinated or perplexed or irritated by the piece, which sometimes resembles a playground for smart, handsome, dysfunctional athletes, and at the same time wondering fitfully just what minute-by-minute commands and given structures are influencing the performance of Sider on any given night.

Forsythe, whose company is based in Dresden and Frankfurt am Main, has said that he keeps “trying to test the limits of what the word choreography means.” You could see that even in his earlier cranky, ice-sharp ballets, such as In the Middle Somewhat Elevated, which grace the repertories of companies worldwide. His influence has been enormous, too, via projects that extend beyond his own choreography—for instance, his 1994 computer application, Improvisation Technologies: A Tool for the Analytical Dance Eye. His company members—a few of whom have been working with him since the late 1980s, when he headed Ballett Frankfurt—are remarkably astute; brilliant mental and physical gymnasts. Imagine what it takes for a performer to cope with Forsythe’s practice in relation to Sider. This is his explanation: “We work here with very powerful formal systems, but I continually shatter their logic by inserting exceptions. But before they notice that, I also shatter that logic by inserting exceptions to that exception.”

No wonder the performers in Sider sometimes pause or freeze; perhaps they’re putting their brains back together. You can glean some of the elements they must cope with. All of them wear tiny earphones, through which they hear text from a late 16th-century tragedy. They ignore the plot and move to the rhythms of a film’s soundtrack of the play, aligning with a character during dialogue passages (I’m thinking Shakespeare and iambic pentameter and the sweep of a blank-verse sentence). They also occasionally hear the voice of Forsythe commenting or giving instructions. In their heads, they carry city maps that they have designed; they may travel through these and/or semi-construct their contours with the cardboard slabs. Forsythe wants to promote an air of “anxious anticipation,” and his tactics elicit just that.

This last bit of information helps to explain the first few moments of Sider. Frances Chiaverini and Fabrice Mazliah are moving in close proximity. She wields two of the cardboard sheets; he adjusts his own body in various thoughtful ways. At moments, you think that she might plan on scooping him up or building something with his cooperation, but you can’t discern a joint purpose or relationship. The two are following separate maps; because they’re working so near to each other, the maps overlap.

The environment in which this society works and plays is a cheerful one, despite the array of overhead fluorescent tubes that wink off and on at times (“light object” by Spencer Finch, lighting by Ulf Naumann and Tanja Rühl). On rare occasions, a sentence is projected above the stage. One says, “she is to them as they are to us;” another other says, “she is to that as this is to him.” Yes, these eighteen dancers have separate agendas; yes, they are both performers and spectators of others’ performing. Dorothee Merg has dressed them in vivid outfits that feature eccentric floral or camouflage prints, plus bright-colored jackets and hoods or ski masks. One of them (Riley Watts, as I recall) wears a huge white ruff and a dark suit that refer us to Elizabeth I’s reign). David Kern is a vision in pink as he crouches behind a panel, jabbering in a made-up language. A couple of the panels bear words; his says “in disarray.”

The inhabitants of Forsythe’s Sider. (L to R): Dana Caspersen, Fabrice Mazliah, Frances Chiaverini. At back: Ander Zabala. Photo: Julieta Cervantes

Never have you seen such elegant depictions of controlled disarray. Consensus appears out of nowhere. At one point, dancers start galloping around the stage, holding the panels in front of them horizontally. As they go they bang the panels ahead of them with their knees. The aural-visual image that pops into mind is of a bunch of Monte-Python knights riding into battle. Only occasionally does everyone agree on a single action—for instance, to form a tableau together or to face us, holding the boards in front of themselves, as if to wall off a jury box.

The controlled disarray applies to their bodies too, whenever anyone stops building something or wandering around listening to the voice in his/her ears and starts to dance. Forsythe is a master of the deconstructed body, of the sensual tug-of-war between, say, a dancer’s hips and head and shoulders (Mazliah is a marvel at this). The performers in Sider also have a way of disappearing behind the cardboard props; at one point, a few of them build their own little Tower of Babel to shelter in.

Although they may scamper around or drop into a bit of hopscotch or spar with one another, they don’t appear particularly playful. Nor do they often communicate verbally; Dana Caspersen and Kern do speak at each other (I can’t recall their words). Kern, popping from one side of a panel to the other, speaks for two different characters in the play, suiting his gibberish to their dialogue.

In the last few minutes of Sider, the piece winds back to its beginning. The same small, precarious arrangement of several panels stands where it stood when the curtain rose. Again, Chiaverini and Mazliah pursue their individual paths, although she appears to be having some trouble with her cardboard sheets. Kern is talking quietly. All is as it was, only not.

We’ve been seeing and appreciating many of these multi-national Forsythe collaborators for a number of years. Yoko Ando, Cyril Baldy, Esther Balfe, Caspersen, Anancio Gonzalez, Kern, Mazliah, Tilman O’Donnell, Nicole Peisl, Jone San Martin, and Ander Zabala are familiar faces (assuming we can see their faces under those hoods). Katja Cheraneva, Chiaverini, Brigel Gjoka, Josh Johnson, Natalia Rodina, Yasutake Shimaji, Ildikó Tóth, and Watts are comparative newcomers to the group (although Tóth has worked in the U.S. with Susan Marshall and others). I list their names not just because of their contributions to Sider as choreographers and on-the-spot improvisers, but because they are such vivid and daring performers in what I see as a puzzle that has no correct answers, a maze with a lot of dead-end streets, and a not too stressful vision of an adult recess in the school days of life.

It IS fascinating. Thanks for your astute writing.

“No wonder the performers in Sider sometimes pause or freeze; perhaps they’re putting their brains back together.”

Not to mention our brains as well.

I’ve been thinking lately about pattern-making choreographers. Tharp was just here, with a new work for PNB, and while I’ve been mulling it over I watched some Humphrey as well, and now the two women are linked in my head making movement puzzles for us to solve. I get the same feeling from the Forsythe I’ve seen, and from your evocative descriptions here it sounds like he’s still building those Rube Goldberg phrases, winding up the mainspring, and then seeing how it all goes.