The Asia Pacific Dance Festival in Hawaii and the Prince Lot Hula Festival

Flowers everywhere. On trees and the ground beneath them. On shirts. Around necks. And, I like to think, blossoming in the minds of those attending the Asia Pacific Dance Festival at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. Co-produced by the University’s Outreach College and the East-West Center Arts Program, the biennial Festival—now in its second year—brings together the artistic traditions of several Pacific Rim countries, both in performances and in the courses offered in a three-week Summer Intensive.

In the theaters and studios of the campus, the idea of journeying—a theme of the 2013 Festival—could apply both to venturing outside the traditions you know and to carrying your own cultural traditions in new directions. I didn’t arrive in Oahu in time to see the performance by Samulgwangdae – Dance and Drums of Korea, but this group and the three that shared two later programs offered dances that were indigenous or strongly rooted in tradition, plus those that took in contemporary ideas and forms. During the five days I was at the University (primarily to take part in a forum and a class), company directors and choreographers talked like skilled and cautious hybridists—eager to expand their native culture without compromising it or losing its essence.

The camaraderie and the curiosity about—and respect for—the traditions of others was evident from the official welcoming ceremony, held in the grassy, tree-shaded Friendship Circle beside the campus’s East-West Center. Each of the two visiting companies who would share the upcoming programs in the campus’s architecturally splendid John F. Kennedy Theater opened brief windows into their respective styles.

Performers from Michael Pili Pang’s Hālau Hula Ka No’eau at the Festival’s Welcoming Ceremony. Photo: Gregory Yamamoto

Setting aside the nuances of those styles, you can discern some obvious contrasts. Gifted members of the just-graduated class of the Taipei National University of the Arts, maintain a moderately narrow stance and step-hop footwork, as they chant rhythmic syllables and snake through an indigenous Taiwanese chain dance, Performers in New Zealand’s Atamira Dance Company maintain a wider, deeper stance, nor do they exhibit the lusty joviality of the TNUA dancers. At the beginning of Haka, a piece rooted in Maori culture, a leader (Moss Patterson) chants and swings a bullroarer, while those behind him stand quivering their hands at their sides, as if summoning up energy from the ground; repeatedly, they drop to one knee to pound a fist against the earth; they widen their eyes, puff out their cheeks to expel air, grunt, yell, and show their tongues.

When members of Michael Pili Pang’s Halau Hula Ka No’eau dance to chant and percussion, you see a softer relation of the dancers’ feet as they tread the grass. Unlike the performers in the other two ensembles, they sway their hips as they dip and turn from side to side, and their gestures focus on aspects of the nature around them.

A little mixing begins. The students there for the intensive have been learning the Taiwanese folk material and jump up to join the TNUA dancers during the last moments of their dance, kicking off flip-flops on the way. Kumu hula Vicky Holt Takamine responds to the New Zealanders in her native tongue (offering, I believe, a warrior chant in honor of Pele, the Hawaiian goddess of volcanoes and other fiery things). Leis are draped around necks and symbolic wooden poi pounders are bestowed. Then all go into the Center for food, drink, and conversation.

Students in the three-week intensive join Taipei National University of the Arts dancers at the Welcoming Ceremony. Photo: Gregory Yamamoto

It’s fascinating—often moving—to see what happens in the classes that follow the morning lectures. One day, the TNUA dancers come to the studio where the students enrolled in the Intensive (all women, mostly college undergraduates from mainland U.S.A.) have been learning a dance of the Puyuma people. Some of the Taiwanese perform a version first, with one of the young men, Hwang Li-Chieh, leading the line and chanting in a strong voice; finally in a tight circle, they throw in some flying leaps. Then they sit to watch the students. The steps are relatively simple, but these dancers have learned from Amin Balangatu, TNUA’s teacher of indigenous dance, a long complicated call-and-response chant to accompany the movement. The distinctions between “Hi Ye Yan O Hai Yan, Yi Ya O Ho Hai Yan Yoi Hai” and “Yin Hoi Yan Ho Yi Ya O Hai Yan, Ho Yoi Ha Hai” aren’t easy to master and belt out. The TNUA kids look surprised and not a little impressed. Then the two groups merge, sitting in pairs to chat and rising to chain-dance together.

The Taiwanese performers are interested in hula, so Pang and Takamine give them a class. Young, lithe, and highly trained (the program at TNUA is a conservatory-style one), the dancers have no trouble getting their hips moving or working in a bent-kneed stance, but once they have to add the gestures that acknowledge the mountains and the waves, their legs get a little straighter; too, their hands tend to look more delicate, less sensing pressure than those of the hula masters. Yet they dig enthusiastically into the style, get it, enjoy it.

The judiciously programmed events in the theater mingle the companies—both for variety and to eliminate delays for costume changes. Just how Atamira, the TNUA group, and Robert Uluwehi Cazimero’s Hālau Nā Kamalehi O Līlīlehua approach and develop traditional material varies. The Taiwanese contingent presents an indigenous dance at each performance (learning their heritage is part of these dancers’ training). Wearing the appropriate costumes, chanting and dancing in a long hand-held line, they dance a celebratory annual ritual of the Puyama tribe and three chants and dances from the Amis tribe.

The company also shows work by young choreographers within its ranks—ones who’ve had four years of ballet and contemporary dance classes. In The Man, Cheng Yu-Chen moves four dancers in hip casual attire through excerpts from Antonio Vivaldi’s Concerto Grosso in D minor, adhering to the music’s structure while allowing them to show how clean-lined, yet kinkily flexible they can be. And, yes, a snatch of b-boying sneaks in. Chou Chen-yeh’s very stylish Chapter derives its structure from literature (strokes into words into sentences, etc.), and the seven dancers in white tops and dark blue pants build their channeled patterns to Michael Torke’s music, like pedestrians yearning to get a bit wild (a bit more hip-hop ensues).

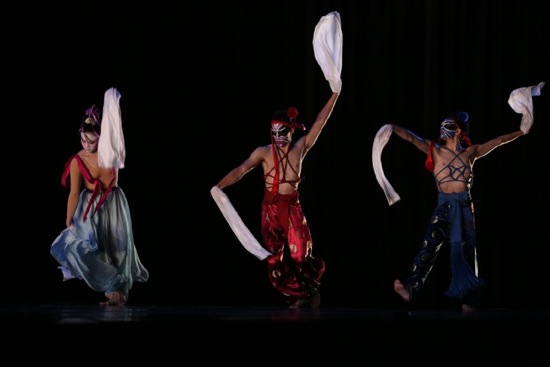

TNUA dancers (L to R) Hsu Tzu-ching, Huang Li-chieh, and Lin Zheng-xin in Lin Hwai-min’s Milky Way. Photo: Gregory Yamamoto

A classic, Lin Hwai-min’s Milky Way, fills the gap between the indigenous material and the modern dances that could—almost—have been made in any country. Milky Way was choreographed in 1979 when Lin had barely begun to seek Taiwanese themes. In creating this vision of gods and goddesses who roam the Milky Ways planets, the choreographer refers to Chinese Opera, while using structural techniques derived from the western modern dance he studied. The dancers wear costumes adapted from traditional ones, and the men have the elaborate painted faces of Opera characters. Unlike Lin’s recent works for his Cloud Gate Dance Theatre, Milky Way doesn’t shy away from overt virtuosity, although the feats are Asian in style and manner. Now it’s not likely that he would have a woman (Kuo Yu-ching) extend her leg high to the side and stand balanced on the other for a very long time, or a man (Wei Chu-han) grasp one of his legs and points it up to 12 o’clock. Someone (Lin Yi-ching, I think) is flipped through the air and into a backbend. When Huang Li-Chieh strikes a deep lunge, as if to silence all opposition, or flashes a sword, you understand that things are no more peaceful up in the galaxy than they are on earth.

Atamira doesn’t presents Maori ritual dances in their original form, but adheres closely to the style and intent. As the program note for Haka explains, the choreographer, Ross Patterson, has “developed and contemporized” traditional movements to fit this group of eight powerful dancers. (The purpose of a haka is to call a tribe to action. Mana, or collective pride, is what the apparent ferocity is all about.) It’s the same with Gaby Thomas’s Pou Rakau. She based her rhythmically vibrant piece on a traditional Maori stick game, plus martial arts, and set it to music by Peter Hobbs. The seven dancers are as much weapons as the sticks they wield, and founding company member Jack Gray’s entrance, wrestling with a bundle of extra-long sticks, tells a whole other story.

Maori tattoo practices inspired Patterson’s Moko, along with games and martial arts. In this last, the dancers cartwheel, vault, feint with and lift one another. Three people holding hands tackle a strenuous exercise in pulling and tangling. Nancy Wijohn and Kelly Nash, grappling intricately, are as tough as the men (Mark Bonnington. Daniel Cooper, Andrew Miller, and Gray).

(L to R): Atamira’s Mark Bonnington, Kelly Nash, Jack Gray, Bianca Hyslop, Andrew Miller, Nancy Wijohn, and Daniel Cooper’s elbow in Dolina Wehipeihana’s Poi E Thriller. Photo: Gregory Yamamoto

The most thoughtfully contemporary, if puzzling, of the eight works that Atamira brought to Manoa are Nash’s Indigenarchy and Gray’s Mitimiti.The first expresses the contemporary confusion over Maori identity, but it’s structured like children’s games with a Mexican rug. This colorful weaving morphs rapidly from a cocoon to a queen’s train to the backdrop for a sort of Punch-and-Judy fight to a covering that creates a two-person female centaur.

In Mitimiti, each of the dancers seems to be on a private journey into his/her own identity and influences—leaping and collapsing along the way. The piece resonates with references we may not fully comprehend; watching it is like wading through a swamp, bright with flowers, but who knows what swims below? Is it because Cooper is fair-haired and fair-skinned that he repeatedly strikes Maori stances with fierce attention? What is Wijohn (or was it Bianca Hyslop?))—grunting and retching at a microphone—trying to expel (or articulate)? Miller attempts a shot with a golf club. . .the heritage of colonialism, or something more personal, less political? Women whip their hair around. Act sexy. One wraps a black scrim around her head and writhes. Bonnington treats the same gauzy curtain as something to be floated out of his way. And, after the enigmatic, vivid events, he steps to the mike and says to us, “Have a pie?” (I feel like shouting back, “Have a pie ???)

Robert Uluwehi Cazimero’s works for the members of his all-male halau approach tradition and innovation differently. In hula, you can perform a handed-down kahiko (or ancient) hula or create a new hula in kahiko style, using traditional percussion instruments and elements of traditional costuming. Or you can go for one termed auana, which may use ukulele, guitar, or (in Cazimero’s case) piano, and which illustrate songs (mele) about contemporary topics or timeless ones (like love). The men in this group don’t venture into anything that looks like modern dance. Their resiliently treading feet, their knees that snap rhythmically apart, their bending and swaying support gestures that speak of the environment and human feelings, or tell stories of the gods (or more up-to-date tales). Hula music doesn’t accompany dancing; it’s the other way around.

In Cazimero’s Trilogy, three men (not singled out in the program) perform traditional solos. They wear headbands, leis and other necklaces, and draped skirts; he plays drums. In Lamalama O Mamala (adaped from Manu Boyd’s original version for women), the men chant along with Cazimero, while he plays a gourd; they also sing in western harmony. And it seems to me that kahiko and auana also come together in the way the men enter for this hula relating to a shark goddess; they walk, bent forward, in seemingly random patterns, like fish seeking to merge in a school.

Others of this hālau’s presentations, contain even more un-traditional elements. Cazimero plays the piano while singing two songs, Hola ’E Pae and Leahi,and fourteen men in trousers and bright shirts with leis around their necks join in, staying in their spots, their hips mobile. Waiting for someone who never comes, they check their wristwatches in unison. E Mai/Both Sides Now is built, in part, on a recording by Sharon Culetta of Joni Mitchell’s “Both Sides Now.” Cazimero embellishes the song with his own voice, and the men give the words physical life—first simply standing in place and gesturing fluidly, then moving into new formations as they continue creating the images.

Cazimero’s voice is wonderful—not a very deep one and, in at least one piece, able to provide high obbligatos above the men’s chanting. These men are beautiful to see—some young, some older, some tall, some short, some slim, some sturdy. Because they often tell of women in their dance, they embody both masculine and feminine aspects of humanity in subtle and tender ways that are very moving.

Two programs, seventeen dances—some of three or four-part. A provocative cross-cultural luau—a feast of music and dance with many ideas and questions to digest in its aftermath. A journey for sure.

The day of the APDF’s opening performance, another festival took place at the Moanalua Gardens from 9 A.M. until after 4 P.M.— the 36th Prince Lot Hula Festival that takes place every July.

The non-competitive festival is named for the 19th-century royal youth who became King Kamehameha V. During his reign, hula and other traditional practices were revived from the limbo (or worse) to which Christian missionaries and others had assigned them. Various ceremonies, speeches, and chanted and danced prayers open the Festival, which is set on a vast lawn surrounded by enormous trees and edged by booths selling crafts, clothing, books, food and drink. A cordial, well-known radio announcer keeps us informed about the hulas being performed on a grassy hula mound consecrated to Prince Lot’s beloved, the priestess Kama’ipu’upa’a. (How can a language so vowel-studded sound so flowing?).

During my nearly five hours in the Gardens, I hear mele that evoke fragrant maile flowers, wind, sea, rain, mountains, sunrise, a pond, the beauties of Kaua’i, and more. Queen Emma, King David Kalakua, and historic figures are celebrated, as is the sexual prowess of Prince Lot’s younger brother. Several songs refer to the famous storm-tossed travails of Hi’iaka, the little sister of the goddess Pele, whom she offended through no fault (almost) of her own.

Michael Pili Pang’s Hālau Hula Ka No’eau performing at the Prince Lot Hula Festival. Photo: Joe Solem. Courtesy of Moanalua Gardens Foundation

And then there are the dances that accompany these—dances that step to the rhythms pounded out on huge gourds, on smaller ones by the dancers, on shaken ‘uli ‘uli, on drums. The performers’ traditional costumes are taken for granted, but sometimes the missionary influence startles me all over again—not so much the pantalettes, full skirts, and blousy, unrevealing strapless tops that the women wear, but the frequent sight of men wearing long-sleeved, solid-color shirts, ties, and black trousers —plus skirts and leafy wreaths around their brows.

You can relish some highly accomplished dancing. The best of the performers sink deeply into their steps, rising slightly only to sink again, although one beautiful woman soloist from the Hālau Hula O Maiki of Coline Aiu—a third-generation kumu hula— rises slightly onto the balls of her feet as she turns from one side to the other. When the dancers of the various groups step into half and quarter turns, their skirts billow slightly behind them; the fabric also sways with their hips and responds discreetly when they whip their knees open and closed. Although the performers face front for the most part, their dancing looks three-dimensional because of the partial turns and the way their gaze shifts and their bodies incline to follow gestures that point diagonally down to the earth or up to a mountain or higher still to the clouds.

Each of the major hālaus (I saw five) has its own emphasis, but the non-competitive nature promotes a family atmosphere (among the spectators too). The hālau of Vicky Holt Takamine and Jeffrey Kānekaiwilani Takamine offers not only its adept performers, but some teen-aged girl students and a few really little ones. The members of the weekly class that V. Takamine gives to her mother and her mother’s friends perform too, stately in long blue gowns. Young boys from Michael Pili Pang’s Hālau Hula Ka No’eau appear in his presentation and some very small ones in that by Leinā’ala Kalama Heine’s Hālau Nā Pualehi o Likolehua.

This visit to Hawaii marks the first time I’ve sat on a panel with flowers around my neck. How traditional is that? How evolved?

Images at dance festivals and hawail beautiful performances here are very good. good gig going well

A lovely rendering of your experiences at the Asia Pacific Dance Festival Deborah. Through your descriptions I’m surrounded by those warm trade winds and the scents of Plumeria and volcanic earth and can picture the color and weight of each performance. Yes, panelists wearing flowers are evolved! You could start a new trend….

all the best, and thank you,

Lodi

after reading the article I felt the style blend between Asia and the West, all the same tone as a natural integration.