Kyle Abraham/Abraham.In.Motion presents Pavement at Jacob’s Pillow, August 21-25

Kyle Abraham’s Pavement. L to R: Matthew Baker, Chalvar Monteiro, Maleek Washington, Rena Butler, Jeremy “Jae” Neal, Eric Williams. Photo: Em Watson

You walk down a street in Pittsburgh’s Hill District. No, you don’t walk, you saunter—loose-limbed; cocky; taking big, easy steps. You are a young black man, and this is a decades-old black neighborhood. Does your leisurely progress identify you as a power—a drug dealer, maybe? A gang leader? Or are you a nervous kid trying to look as if you don’t scare easy?

When you watch Kyle Abraham’s Pavement, you’re never sure which you’re seeing.

Into this devastating and hopeful (2012) work, Abraham has woven the history of his birthplace, a community where jazz flourished in the 1950s and small businesses lined the main street, and later a dilapidated terrain where drug wars spill from housing projects into the streets. His own history colors it all—his boyhood lessons in art and music, the many kinds of dance he has studied and performed. Pavement has no single narrative; its atmosphere is that of a dream in which images form, dissolve, overlap, and recur. A dream in which the fallen rise and walk and, at a later time, fall again. A dream in which a casual gesture can ignite violence between two people, yet end in an embrace, with no transitions between states.

Dan Scully has designed the bare hint of a neighborhood within Jacob’s Pillow’s black-box theater. The floor is gray, its boundaries outlined in red-orange tape. From time to time, light creates sidewalks. High up on the ersatz chain-link fence at the rear is a basketball hoop. Its backboard also bears a taped rectangle. On this board, late in the dance, video images appear. No one plays basketball, or even thinks about playing basketball (although maybe a jump shot lurks in the choreography).

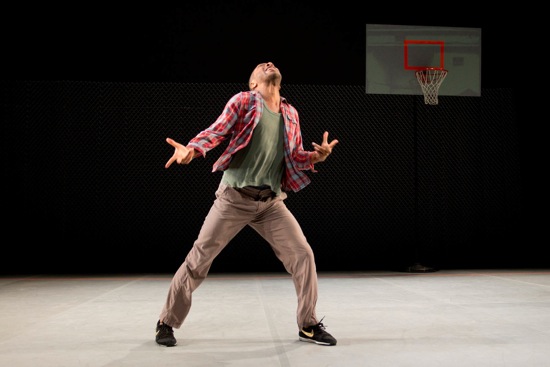

The six performers (who also collaborated on the choreography) are people on the move. Where are they’re going, where have they just been? Hard to say. But they also hang out, play cards, and pick fights. And dance. Lord, how they dance! Very occasionally they mutter something, mostly in slangy street-wise banter. But dancing is their language. It keeps them at work. Keeps them at peace. Keeps them alive. Almost. Alone onstage, Abraham introduces the vocabulary. His movements are wide and low, and they flow like honey—trickling into a shoulder, an elbow, neck, pelvis, making his knees buckle and his feet slide along the floor. He wings his arms behind him; his leaps stretch out in space but often barely leave the floor. He gets even closer to the ground with one-handed, hip-hop-style cartwheels, and breaks the sinuosity with swift twitches and gestures that seem to tear his immediate surroundings apart.

Sometimes he, like the other marvelous dancers in the piece, suspends a movement for a second —lets it breathe—but the ground is home. And although the texture of the dancing is lush, it’s not verbose. Abraham has barely started Pavement when he stops and stretches one straight arm down and a little in front of him. He stares at that arm for quite a long time before it whips back into action.

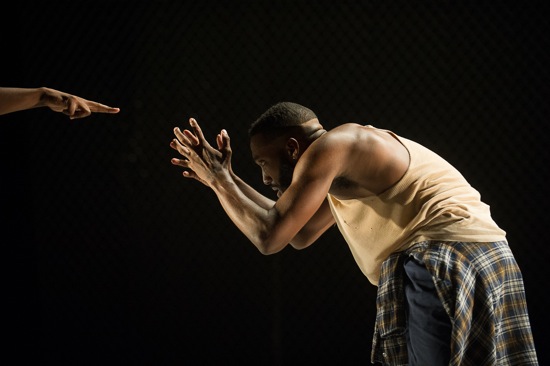

The passage that follows introduces a motif that will become increasingly grim over the course of the piece. Chalvar Monteiro enters and starts doing his own juicy thing alongside Abraham. Eric Williams strolls on and carefully, almost gently, lays each man face down and crosses his wrists behind him. Monteiro stays that way, but Abraham keeps rising and dancing again twice more—faster each time until he’s almost hysterical—and twice more he’s laid out. Then Williams walks off, chatting with a new arrival, Matthew Baker. Abraham and Monteiro get up and begin dancing— facing each other, grinning. No big deal (or was it?).

Dancing is almost ongoing, Some folks are doing it; others happen by and feed in. And little issues crop up; at one point, everyone is working in unison, but Rena Butler—the only woman in the group—holds someone else’s shoulder while she’s doing the steps. A gesture of holding both hands up suddenly means —if only for a few seconds— that an invisible gun has entered the goings-on.

Abraham’s eclectic choices abet the dreamlike order of things and lay down an emotional subtext. The sour-sweet folk song to guitar by Fred McDowell and Alan Lomax is succeeded by an aria from Johann Christian Bach’s La Clemenza di Scipione sung by countertenor Philippe Jarousky. Over the course of Pavement, Jarousky’s gorgeous voice pours over the dancing in arias by two Baroque composers, Antonio Caldara and Antonio Vivaldi. But the blues and more recent pop music play their part too. And whatever beauty music provides, the sounds we hear are frequently gunshots, explosions, and yelling, screaming voices.

The men don’t make a big deal out of Butler being a woman, although sometimes guys crowd in on her and she raises her palms in a “back-off” gesture. When she slides into a duet with Maleek Washington, she tackles every close embrace doubtfully, as if she doesn’t dare trust this tenderness to last. Their flesh-on-flesh encounter is very different from the way one man sometimes picks up another as if he were a log and wrestles him into unsatisfying positions. Imagine landing a big, slippery fish you can’t control.

Running can spring from many motives, and running in a circle from even more. One by one, the performers join in an easy, springy, athletic stride, which can get bigger and faster or smaller and tighter, until they’re a jogging phalanx. Abraham, running alone and covering a lot of ground, gives you time to think of all the places, people, and ideas he’s thinking of escaping.

Occasionally, a more literal drama appears. People cross the stage, going about their business, while Abraham, standing at the back of the stage, implores someone to “Help me out.” “Please.” No one pays him any attention. A red light is flashing. He becomes increasingly distressed—whimpering, sobbing. These are his people; he’s one of them. Why won’t they give him some money? In front of him, Washington and Jeremy “Jae” Neal devour their dancing as if it’s the only meal they need. The ways in which Abraham structures Pavement and his distanced handling of violence, rage, and tragedy give the piece a power beyond what it might have had as a dramatic narrative with an overt social message.

The handcuffed image dominates the final moments. Abraham has being lying inert for some time. On the backboard, an image of an immense housing project appears. A second later it explodes, raining down fragments As the musical selections play on (has someone fed a jukebox?), Monteiro enters with a bag of chips and sits right beside Abraham; for a few minutes, the only sound is of him crunching on his snack. After he is up and dancing again, Williams enters and touches his head; Monteiro collapses, is laid out, dragged to a new spot, and “cuffed.” Then Williams lies face-down on top of him. Washington walks in and lies on top of Williams. Sam Cooke is singing, “I Belong to Your Heart.” For a long time no one moves.

Now begins a potentially endless ritual of replacement—excruciating in the participants’ acceptance of it. Monteiro worms his way out of the pile and becomes its top body. Butler enters and lies down of her own accord. Neal drops down on top of her. For a second or two, she works her way onto her back and holds him above her. As the changes of place continue, the highly individual dancers become increasingly anonymous—objectified in some way. We’re left with Abraham, still motionless and alone, and two piles of those who were dancing so wonderfully not so long ago. The last song? Donny Hathaway singing “Some Day We’ll All Be Free.”

Hi Deborah,

Another terrific review. How I’d love to see this work. Would especially love to see it performed as a companion piece to one of August Wilson’s great plays about Pittsburgh. (“King Hedley II” for instance).

From your fan in the islands.

Carol