“The Painted Bird,” a trilogy by Pavel Zuštiak + Palissimo Company, at LaMama Moves! Dance Festival, June 21-30, 2013

Pavel Zuštiak’s The Painted Bird trilogy draws its themes from Jerzy Kosiňski’s much debated novel of that title. Images of flight, concealment, disguise, isolation, displacement, and the vagaries of memory pervade all three parts of this extraordinary work. What does the traveler, the fugitive, the exile carry and what is left behind?

Zuštiak and the members of his company, Palissimo, want us to experience first-hand a hint of what Kosiňski’s protagonist—a small orphaned Jewish (or gypsy) boy on the run in Eastern Europe during World War II—and all outsiders like him felt (and feel). Those of us who saw the three parts when they first played in New York had to travel sporadically: from LaMama and Bastard in 2010, to the Baryshnikov Center and Amidst in 2011, to the Synod House of St. John the Divine and Strange Cargo in 2012. The very difference spaces were like foreign countries; our perspectives had to adapt, and our memories of what we had seen before were blurred by time.

The LaMama Moves! 2013 (a festival that runs through July 7) brings all three pieces together in a four-hour performance, broken by two intermissions. Our sense of transformation and dislocation is more acute. When we return from the first intermission, our seats at one end of LaMama’s Ellen Stewart Theater are no longer available, and the space in which we now must wander is dark and full of fog. After the second intermission, the chairs have returned, but now they are set in two rows on both the long sides of the space. Spectators on the opposite side from us become part of the backdrop, being watched as they watch.

In this marathon evening, our memories don’t fade as easily as they did over the course of a year. Now in Amidst, when Elena Demanyenko, ghostly behind a scrim, begins to make gestures with her hands, we recognize them. They remind us of gestures that Jaroslav Viňarský makes in Bastard, where they seem like elements in a half-comprehensible sign language. Some of these appear again as poses in Strange Cargo. In the first moments of Bastard, one man (Zuštiak) and then another (Christian Frederickson, the marvelous composer and musician for the piece) enter and lie face down in different spots on the floor, sliding their arms into position by their sides; several times, each rises, moves to a new place, and carefully assumes the position. The three superb performers in Amidst, Demyanenko, Nicholas Bruder, and Zuštiak, lie close together in the same way, but they buck and arch in order to inch forward, and roll over one another to change places.

Bastard is primarily a solo for Viňarský, a choreographer-dancer born in Slovakia and active throughout Eastern Europe. Lord, what a performer he is! Wiry, muscular, not very tall, he’s as alert as an animal, precise in his intentions and soft on his feet, with expert dramatic timing. Silhouetted at first in Joe Levasseur’s superb lighting, he stands with his back to us, his head hooded, his legs bare. He’s wearing a loosely cut, rust-colored jacket, and when he lowers himself into a squat, its hem almost touches the floor. This now-small person now begins to walk. In a squat. He traces the red-taped perimeter of the large performing area four times. When he advances toward us, maintaining the position makes him waddle like a grounded bird. He cuts smaller squares, hurries, falters, falls, continues; his path begins to waver, to curve. After what seems a very long time, he collapses, and the lights go out briefly. Any dancer or former dancer in the audience is likely to sense how Viňarský’s knees must feel during this ordeal, which can be seen as eloquently symbolizing a stoic child’s flight through unfamiliar territory.

Only now does Frederickson become visible on the small stage at the end of the space. Alternating between violin and guitar, and adding electronic elements of the score, he invests events with crucial atmosphere and drama. So does Levasseur’s lighting. After Viňarský, coatless, has performed a wild and drastic solo—rushing, falling, rolling, somersaulting backward, bumping along on his belly, the terrain changes for him and for us. Suddenly a staircase to the theater’s upper tier lights up; Viňarský runs to it; the lights go out. As if he has entered an inhospitable village, other stairs and doors light up, only to disappear when he reaches them. Eventually he gives up, and leans against a wall, tries to sleep on a bench.

We see him dreaming or dancing with a remembered partner, but the atmosphere becomes drastic, as a low drumbeat looms under a sweet melody. Terrible words (Kosiňski’s) of rape and torture and cruel death swim, projected, across the back wall. The man trembles, humps the ground, pulls at his nipples. But Zuštiak practices a kind of erasure. Suddenly the terror is over, Viňarský pulls orange sneakers from the box and puts them on; he takes out black makeup and smears it over his face and hands.

Kosiňski’s The Painted Bird takes its name from a tale told within it. In a cruel game, some peasants catch a bird and paint it; when it tries to rejoins its flock, the other birds peck it to death.

Zuštiak subverts this. Suddenly people in everyday clothes come from behind the audience and from seats among us. A horde (45 names are listed in the program). They stare at us; they walk and run in all directions, faster and faster, shoving one another aside. Viňarský, painted or not, manages to blend in. But wait, these aren’t aggressors; they may be victims. Packed together like sardines, they lie on their bellies, their heads turned to one side, their arms down, the same way Zuštiak and Frederickson lay at the start of the piece. One by one, they rise and move to new places in a line closer to the audience. If this wave were to keep moving forward, it would pass over us. Finally, Viňarský extricates himself, sits down, and starts wiping off the face paint.

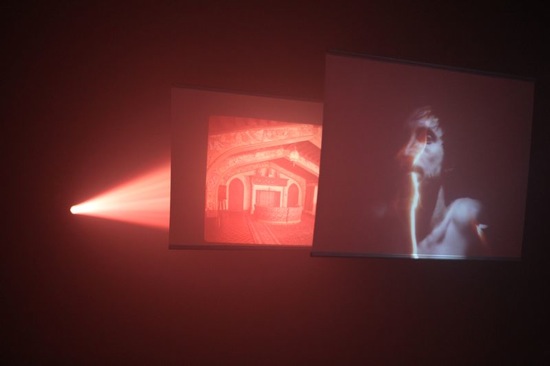

In Amidst, we, like the performers, don’t know where we are. The room is dark and smoky. Now the musicians are Frederickson, fellow composer Ryan Rumery, and William Flynn. We are free to wander around in this limbo, on our feet for 60 minutes. We come upon the three performers, perhaps cluster around two of them, only to turn around and sight another. If we get too close, they push between us. For most of the piece, Demanyenko wears red high-heeled shoes so we can hear her coming and going. There are artifacts. Images of Viňarský, hidden among cloudy designs, appear on one of two small screens suspended at eye-height (photography, Robert Flynt, video design Keith Stretch). Confusing green and red lines and arrows, like those on a phantom highway map, appear and disappear on the floor. Sometimes slim rays of light spread from a single point up high and fall to create a tent of beams. On one large suspended sheet, portraits dissolve into one another—some from the 19th century, others contemporary. Searchlights pierce the darkness.

Once each of the three dances alone, briefly replacing one another in a circle of light, perhaps affirming their identity, They struggle together. And often they pause and stare into space, as if trying to remember where they are. That’s what Zuštiak does in one potent episode. The other two keep bringing bundles of clothes, stripping off what he’s wearing, and re-dressing him. No sooner is he in his new attire than one of them removes those garments, and the other brings a new outfit. Gazing into the distance, Zuštiak obediently lifts a foot or an arm. Identities slip on and off him before he can get comfortable in any one of them. It’s a brilliant, alarming scene.

On the night that I’m among the wandering spectators, I notice they tend at times to want to back away from the center and get a good view of the whole space; that’s alarming too. When some audience members close in, the performers are hidden from others; when we open up the space, the three seem more vulnerable—their private efforts to solve some problem too public.

Strange Cargo (The Painted Bird – Part III). L to R Jeremy Xido, Jaroslav Viňarský, Nicholas Bruder, Denisa Musilova, Giulia Carotenuto. Photo: Emily Boland

Because of unforeseen circumstances, Demyanenko replaced Lindsey Dietz Marchant in Amidst on quite short notice, and Viňarský took her part in Strange Cargo. For anyone who saw the pieces at their premieres, this adds to the feelings of displacement and instability that Zuštiak wants, I think, to convey. You can’t, said Heraclitus, step into the same stream twice. Elements of Strange Cargo that I wrote about a year ago (https://www.artsjournal.com/dancebeat/2012/05/hiding-in-plain-sight-becoming-the-other/) have altered or vanished; others appear new. I think. Seeing the piece as the last event of a four-hour evening means that my own perceptions are less acute than they were then. In a sense, I, like the five persons in the piece, are coming to a “home” that is not exactly as I remembered it and one that I may see differently.

L to R: Jeremy Xido, Denisa Musilova, Nicholas Bruder, Jaroslav Viňarský, Giulia Carotenuto in Strange Cargo. Photo: Emily Boland

The beginning moments of Strange Cargo affected me strongly in 2012 and still do. The five fascinating performers enter on their hands and knees, one by one: Jeremy Zido, Denisa Musilova, Giulia Carotenuto, Bruder, and Viňarský. They move determinedly and efficiently, pausing occasionally like wary animals. This time, I see them as finding their way home—whatever home means to them. At first, like Viňarský in the opening of Bastard, they travel in straight lines, although on separate trails. But as they pick up speed, these paths become more eccentric. They knock into one another. Zido bumps his head on the leg of a wooden table. They add odd, almost mechanical vocal noises to the single piano note that ushers in Frederickson and Rumery’s score.

They behave as if their memories have frayed. After they’ve shed some of their garments, Carotenuto holds one of her shoes to her ear: a telephone? Viňarský turns his index fingers into guns and shoots in all directions, making the appropriate vocal explosions, like a kid with a toy. Whatever this society has become, it’s not one in which people trust one another, even as they take turns at challenges like vaulting onto the table. Viňarský sits on chair, shrinking into himself, while, across the table, Xido plays the silent, relentless interrogator. The performers move the standing spotlights into new positions to shed light on whatever they’re searching for, or for their awkward sexual displays. In one startling sequence, they travel in a cluster, the lamp they pull along with them harshly illuminating their slow, cruel tangling and untangling. You imagine a camera recording the trip as a series of images.

Peter Ksander’s two set pieces also have shifting identities. At either end of the space, the poles, set far apart, bear narrow horizontal banners just above the performers’ heads. One of these is mylar and reflects back their distorted images. It’s also seems to be a barrier at which they hurl invisible stones. Their reactions to it—along with the recorded march to which they respond briefly and their “mea culpa” gestures—suggest, with dreamlike ambivalence and disjunction, a society at war with itself. No matter how many times they shuck some clothes or put on others, they remain clothed in their cargo of recollections and associations.

Kosiňski committed suicide in 1991. His note said, “I am going to put myself to sleep now for a bit longer than usual. Call it Eternity.” Some of his words appear on one of the set pieces. But even though Zuštiak’s trilogy is thoughtfully constructed, the choreographer bravely refuses closure and establishes impermanence as an unavoidable aspect of existence. We wander through our memories like exiles.

WOW! That was stunning to read……I’m still reeling from its depth and poetry.