Shantala Shivalingappa’s “Akasha,” a program of new Kuchipudi solos, at Jacob’s Pillow, July 4 through 7.

It was at Jacob’s Pillow in the 1960s that I first saw examples of two dance styles that I’d never heard of: Odissi and Kuchipudi. Indrani, that beneficent performer and promulgator of Indian dance, was giving a master class and had brought with her two male dancers, each of them expert in one of those traditional forms.

What was riveting about the Kuchipudi performer, beyond his rhythmic and spatial skills, was a kind of gender ambiguity. The dance form that developed in a small village in South India was until fairly recently performed by men only. But the stories they told often involved females, whether goddesses or ordinary women. Indrani’s colleague took big, bold, resilient steps, while flirting and playing shy when that was desired. For all the sacredness of the texts and the skill of the performer, you still felt the tension between the male body and the female character, like—yet not like—the way you feel the ambiguities in drag performance.

I understand why Shantala Shivalingappa fell in love with Kuchipudi. This beautiful dancer—born in Madras, raised in Paris—has performed in works by Pina Bausch, Maurice Béjart, Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, and others, but she keeps returning to Kuchipudi. She encountered the form as a teenager, when she went to India and studied with Vempati Chinna Satyam, the guru of her mother, dancer Savitry Nair, and a force in moving the form from its sacred roots and and all-male dancers.

The program that she brought to Jacob’s Pillow this summer is richer, deeper, and more varied than the one she showed there in 2008. Its overall title, Akasha, refers to space —whether the space that encircles the body or infinite, ungraspable space. Shivalingappa performs five solos (all dated 2013), three of which salute divinities: Om Namo Ji Adya is devoted to the intellectually enlightening, elephant-headed Ganesh and to Sharada, goddess of art and knowledge. Jaya Jaya Durga praises the powerful goddess Durga, the conqueror of evil. And the final, Bhairava, honors Shiva, the Lord of the Dance, in his aspect as a destroyer. Shivalingappa choreographed these pieces, and Vempati Ravi Shankar, the son of her mother’s guru, created two narrative works, Krishnam Kalaya and Kirtanam.

In all of them, you can relish the fullness of Shivalingappa’s dancing—the deep bend of her knees, her wide strides, the way her upper body sways from side to side. In Kuchipudi, the dancer’s body often settles into the seductive s-shaped position known as tribhanga; if her hips jut to the right, her ribcage moves left, and her head tilts toward her hips. Shivalingappa gives the impression of a kind of mobility that goes beyond her feet as they carry her through space and accurately present the musicians’ rhythms. Her red-painted fingers flower, her eyes dart, her body twists and spirals and bends. When she spreads her arms, they maintain the beautiful upward curve typical of the form. Delicately built, limber, and strong, wearing a golden costume, she evokes a temple statue come to life.

The musicians are wonderful. On one side of the Doris Duke Studio Theater sit percussionists B.P. Haribabu and N. Ramakrishnan; opposite them are flutist Rajagopal Shakthidhar Vijalapur and singer J. Ramesh. The complex rhythms, the melting singing, and the rat-a-tat vocal syllables that accompany pure dance passages support and embellish all that occurs. And when Shivalingappa leaves the stage for her only costume change, Haribabu with his pakhwaj and Ramakrishnam with his mridangam engage in a witty, virtuosic drum dialogue.

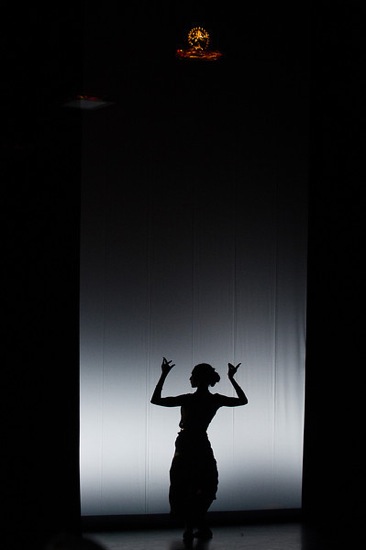

Shivalingappa has arranged the program elegantly, with major assistance from her lighting manager Nicolas Boudier. On either side of the black space, three tiny, suspended platforms rise like steps to a single one at the top, where a small golden figure (Ganesh, I think) sits. Black curtains open slightly at the back to frame or silhouette the dancer in a luminous portal; it is there that she begins, and there that she ends the evening. Her lit hands are the first and last things we see.

The words that her recorded voice speaks and those that are printed in the program illuminate some of her gestures. In the tinkling of Durga’s ankle bells, one can hear the sacred texts, says the poem, and Shivalingappa, sitting, adjusts the bells on her own ankles. In Krishnam Kalaya and Kirtanam, her facial expressions, gestures, and movements tell complicated stories. You may not understand the singer’s words, but you get the gist.

In both these dramatic dances, the performer plays two roles, switching fluidly between them. In Krishnam Kalaya, she bounds onto the stage as the mischievous child Krishna, performing little bent-legged jumps, and expanding Kuchipudi traditions by rolling on the floor and kicking. The musicians laugh. This is one of my favorite Krishna stories. The little-boy god is eating mud. His foster mother hears of this. He denies it. She orders him to open his mouth, and when he does (gasp!), she sees inside it the entire universe. Scolding is now out of the question. Shivalingappa portrays both characters vividly. The resulting joyful dance could be either of them, or both, or simply the dancer praising Krishna—not just the holy child but the enchanting flute-player and lover that he grows up to become.

Kirtanam is even more of a challenge. It’s one of those faithless husband tales. Alamelu Manga (a goddess) is really, really angry. Her mate, the God Venkateshwara, has been dallying with other women. Vijalapur plays the deeper of his two flutes while Shivalingappa sits, disconsolate, on the floor. Is he coming? She goes to an invisible door and looks out. No. She begins to fume. Now the performer moves to the other side of the “door” and, opening it, she re-enters as the happy-go-lucky homecoming husband. The wife is having none of it. “Stop pulling at the trail of my sari! Go away!” says the text, and so say Shivalingappa’s blazing eyes and dismissive gestures.

The dancer must not only switch between these two antagonists, she must show the woman imitating the man’s flirtatious behavior and maybe the women he pursues. To make things even more difficult, the wayward husband becomes charming, coaxing, and the wife’s anger melts. Sometimes it’s hard to tell which one we’re seeing. On the other hand, that very similarity affirms their underlying love.

Over the course of Akasha, we see Shivalingappa joyful, playful, sorrowful, amorous, proud, and fierce. We see her as the virtuoso who, in praise of Durga, can dance out rhythms and travel toward and away from the audience while balancing on the rim of a metal plate, and who, in summoning up Shiva, becomes a celestial athlete.