Brian Brooks Moving Company performs at Jacob’s Pillow, Becket, Massachusetts, July 10-14.

A machine repeats its patterned moves over and over; nothing changes unless one of its parts breaks or something gets caught in the works. Human beings may repeat the same movement many times, but to use the word “same” is simply a verbal convenience. Without meaning to, they may emphasize aspects of the task differently, alter its tempo slightly, favor a tired muscle, breathe more rapidly.

It would be a mistake to label choreographer Brian Brooks a minimalist. Although he often limits his movement palette in a given dance, he works his basic material by augmenting it, varying it, turning it in space, changing which of his dancers (seven including him) will perform what and with whom. Watching any work of his, you may start to think, “This could get monotonous.” You should know better. His works, often physically arduous, are rich with human implications, yet formally pristine. The ordeals that he creates demand skill and endurance, but not competitiveness, not anguish. Although the performers may begin to breathe hard and gleam with sweat, their focus is on the task at hand, not on how they feel about it.

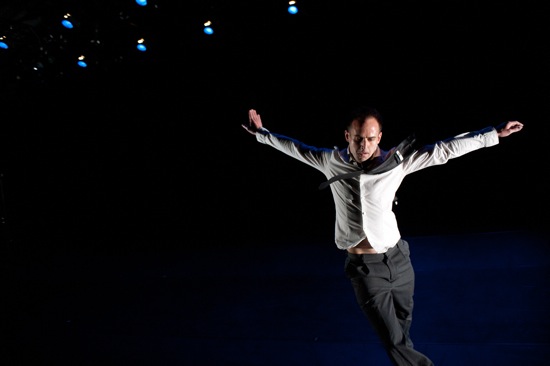

The earliest work on the program that the Brian Brooks Moving Company brought to its season at Jacob’s Pillow, is Brooks’s 2007 solo, I’m Going to Explode. Watching it, you think that an explosion could well happen. The opening suggests a compartmentalized life. Brooks—dressed for the office and sitting on a chair facing offstage—removes his shoes, jacket, and tie and walks into what appears to be a very small space. He moves both arms stiffly from the shoulders, batting them forward as if shoving something away. He’s like a windup toy that needs oil or has hit a wall.

But LCD Soundsystem’s song, “I’m Losing My Edge,” with the lamentations of a been-there dj, goads Brooks on, and he’s not losing a thing. His gestures grow; map new paths. Flowing moves punctuate the rigid ones. He presents himself from different angles, spins, travels out into space—always repeating and building on those repetitions, even as he becomes wilder. Occasionally he reminds us that he’s vulnerable—peers at us or wipes his nose in passing. He’s free, but he’s wilting. Back in his constricted space at the end, he’s pulling a shoe on as the lights go out.

Aaron Walter (L) and Brian Brooks in an earlier (full) production of Brooks’s Motor. Photo: Christopher Duggan

A duet from Brooks’s 2010 Motor, is more limited in its movement vocabulary, but for all its repetitiveness, it’s unpredictable. To a score by Jonathan Pratt, Brooks and Bryan Strimpel hop. For a very long time. I’ll bet you never knew a hop could get so interesting. Side by side, almost shoulder to shoulder, and in perfect unison, the two men cut paths through the space. They hop almost unceasingly—sometimes with one leg hanging behind them, sometime with one leg lifted to the front. They’re not trying to bound into the air (at least, not at first); they’re traveling along some wacky course, and no rest stops are allowed. Sometimes as they bend into their task, you can imagine that Brooks’s choreographic idea was to freeze a runner’s position in mid-stride, and then make it cover ground by means of that low, skidding hop. An amazing idea when you come to think of it.

The guys travel forward and backward. They change directions. They congeal the momentum via split-second arrests. When they add a few running steps, it’s a big deal. When they leap, it’s momentous. When they separate briefly, you fear for their lives.

In his group pieces, Brooks works with support and dependency, as well as with their opposites: solitude and independence. Balance, imbalance, and counterbalance interest him. The newest and most ambitious of these works is the 2012 Big City, which opens the Jacob’s Pillow program. The dancers build that city, or rather, reconstruct it. The black stage floor is covered with slim aluminum pipes. While the audience is gradually assembling, the dancers—moving slowly, gravely, and deliberately—begin to erect a structure. The pipes are in three jointed sections; when hooked onto wires that descend from above and pulled up, they’re positioned so that they present two-angled shapes.

Brooks’s Big City. L: Evan Teitelbaum standing on Bryan Strimpel. R: Jo-anne Lee standing on Meghan Frederick. Photo: Christopher Duggan

The rubble is clearly treacherous terrain. When the dancers attempt to cross it, stepping gingerly, the pipes clatter together. When they briefly lie prone, they look as if they, too, had fallen as a result of some catastrophe. Jonathan Pratt’s evocative original score simmers with variety—melodic passages, ringing tones, insistent beats, and more. Balancing in this shaky world, even after most of the pipes have been shoved downstage, is iffy. Evan Teitelbaum rolls very slowly downstage, while Strimpel, standing on his colleague, adjusts his feet and his weight in order to stay on this fluctuating surface. Later, in a poetic allusion to the rising silver girders, Teitelbaum steps onto Strimpel as he lies prone; carefully Strimpel presses upward into a kneeling position, But because he lifts his upper body first, for a few moments, the man he’s raising is standing on the side of a hill. Meghan Frederick performs the same maneuver with Jo-anne Lee. Lee and Teitelbaum remain serene, gazing into the distance. In another balancing act, Lee walks on Brooks’s hands as he—lying on the floor and turning to accommodate her path—offers them to her. He rolls and swivels; she continues her circuitous journey.

Other patterns suggest other aspects of architectural labor. Danielle McIntosh and Strimpel stand side by side, each with hands joined, and make that “wreath” angle and twist and slip around their heads. Later the arm pattern will travel across the floor as Strimpel and Jeff Sykes run and whirl. Almost always, someone is at the back of the stage, making isolated pipes rise vertically. At some point, hooks begin to descend at a steady pace, and more of the metal pieces are attached and pulled upward. The dancers’ last pattern offers its own architecture, perhaps in homage to what they have accomplished; three couples separate into a V-shaped formation, narrowest at the front, and each pair performs its own set of movements. At the very end of Big City, Strimpel is alone onstage, and lighting designer Philip Treviño changes the workmanlike atmosphere into something more spiritual. The building that the pipes outline—the resurrected city—shines in all its silvery glory. Slowly he backs away from us and enters it.

Treviño’s magic way with lights creates another unearthly effect at the beginning of Descent (2011), the other group work on the program. The dancers enter in pairs, one person bent over and lugging another on his or her back. The one being carried stays stiff. As the couples travel on different horizontal paths, now and then changing roles and directions, horizontal beams from the sidelights illumine them strangely. To anyone familiar with Christian iconography, it’s difficult not to see multiple versions of Jesus bearing his own crucifix. Smoke adds to the mystery, as does Adam Crystal’s original score.

Descent. L to R: Danielle McIntosh, Jeff Sykes, Jo-anne Lee, Meghan Frederick, Evan Teitelbaum, Bryan Strimpel. Photo: Christopher Duggan

Gravity seems to be an issue in this piece. Wearing flesh-colored clothing with hints of glitter (costumes by Roxana Ramseur), the dancers rush and are lifted, fall and are caught, tilt and regain control, unite and separate. Brooks, as might be expected, parses these basic communal acts in unusual ways. One person comes up close behind another, and, glued together, they tip forward, the second person lying on top of the first, who, braced on his or her hands, slowly descends to lie prone. This occurs in several ways—sometimes part of a smooth, three-person exchange too tricky to put into words. A member of this company has to bear a lot while braced in a push-up position.

In one section of Descent, the dancers have non-human partners. Entering and exiting, each performer carries a big, flat wooden rectangle. Above them float pieces of tulle. By fanning the air with the rectangles, the dancers keep the fabric aloft and in motion. These flyers aren’t exactly alike. Frederick’s billowy companion, for instance, is small and white; McIntosh has a much larger pink one.

The object, of course, is to keep these frail puppets from descending. In Crystal’s score, a cello sings above a quiet pulse. The performers must fan vigorously as they walk, keeping their focus up; our attention, too, is on the “other” dancers, who stretch out and curl in, twist and untwist, and soar as if trying to escape.

Without strong support, societies and structures may collapse. So, sometimes, may individuals. You don’t have to tell Brian Brooks that. Nor any of his strong, beautiful, adventurous dancers.