Patricia Noworol strategizes culture and arts politics via hip-hop.

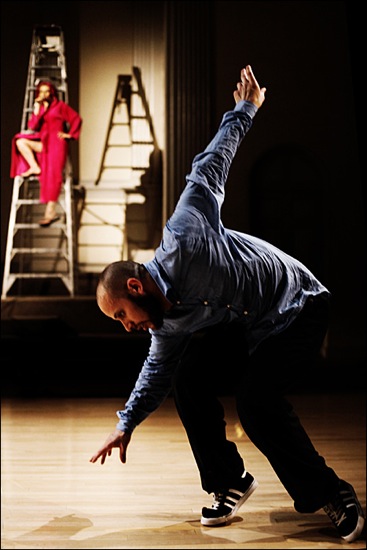

Patricia Noworol Dance Theater in Noworol’s ?Culture. On chair: Patrick Williams Seebacher. On ladder: Noworol. Photo: Aeric Meredith Goujon

Decades ago, some writers considered that ballet was on its way to becoming an international language, despite its obvious roots in western European courts, culture, and dance forms. Other people raised the issue of cultural imperialism. Hip-hop—emerging from American city streets, its roots tangling back to Africa—has outdistanced ballet in its nearly world-wide migration. Battles, festivals, competitions, scholarly articles, classes in universities, choreographies appear in towns and cities miles from hip-hop’s birthplace.

Damn! That’s the wrong way to edge into talking about Patricia Noworol Dance Theater’s performance at St. Mark’s Church (as part of Danspace Project’s DANCE:Access). Too tame, too let-me-set-the picture. Noworol’s witty ?Culture meshes scrupulous designs with brashness, virtuosity, colloquial manners, outrage, and satiric political incorrectness. The music is loud, and the performers, on at least one occasion, use microphones like possible weapons, their voices amplified as if the church were a stadium. Loud or silent, those performers are electrifying.

Noworal currently bases her company in New York (and she received an MFA from NYU in 2008), but she was born and raised in Poland, and a great deal of her recent work has been done in Germany. You might call her a postmodern dancer-choreographer; hip-hop isn’t her forte as a performer. But for ?Culture she has set herself into a small community of men who excel at bboying, popping, you name it. Dodzi Dougban, Sefa Erdik (“Sefa Break”), Shawndrick D. Hallman (“Iron Monkey”), and Patrick Williams Seebacher (“Twoface”) have worked extensively in Germany. Hallman, who mentions that he comes from Alabama, is, I believe, the only American. All have in one way or another expanded their artistry beyond the competitions that have given them prizes.

It’s a provocative mix. Noworol has a mane of blonde hair, strongly accented English, and a killer arabesque (which, fortunately she displays—rarely—as if it were the tail of a comet). Sometimes she speaks as the choreographer-teacher, putting three of the men through their places in what might be a get-in-tune-with-your-body class, as they walk around the church (“Feel the space”). Pretty soon, though, she tells them to “get small” and has them crawling (I think she mentioned cats). In another episode, the men lure her, as if she were a dog they all loved, or a valued token in a game. “Come on!” they gesture and/or call out coaxingly, “come to me.” She runs to each one, jumping into his arms or bracing a hand on his shoulder. Over and over.

?Culture (originally commissioned by Pottporus e.V./Renegade in Herne, Germany) makes no bones about the differences between Noworol and the other performers in terms of gender, heritage, or dance style. Noworol speaks sometime as herself, sometimes as a biased interrogator. At one point, she questions Hallman. “Do you know Pina Bausch?” “No.” “Trisha Brown?” “No.” Neither, supposedly, has he heard of William Forsythe or Robert Wilson. When she mentions Ouspensky, Seebacher, resting on the sidelines, says he’s familiar with that name. Now it’s Hallman’s turn to ask the questions: “You know Crazy Legs?” “No.” “Malcolm X?” No, Noworol says, she doesn’t. Then she asks him to read from a crumpled paper, which he does. It’s a decades-old tract on “the Negro.”

During the questioning, Erdik is dancing alone. He’s remarkable. Over the course of the piece, he will launch himself into a kind of barrel turn—body facing the floor and parallel to it—or a leap from one hand to the other; he’ll drop into a head spin, whip off a super-rapid back flip (maybe a double, I caught it out of the corner of my eye). None of these are isolated as show-off feats to draw applause; they merge into the choreographic pattern. While Hallman is reading from the cringe-inducing paper, Erdik and Seebacher tangle slowly in intricate ways—part fight, part affectionate merging.

At the end of the work’s second section, Norowol squats on the floor and asks questions of the audience. One of these is “How many of you know what this piece is about?” We seem to be stymied, although a few people behind me may have raised their hands. And what is it about, beside facing down taboos and crossing artistic-cultural boundaries? If this audience seems slow to decide, it may be because when Noworol delivers an important concern into the mike, the resonant acoustics of the church and her foreign accent sometimes make it hard to decipher every word.

Also, although her anger involves lack of funding for risk-taking choreographers, her examples are drawn mostly from her recent experiences in Germany. (She was denied funding, she later explains, by six of the agencies she applied to; she reads a rejection letter. Her

proposal involved homosexuality among hip-hop performers.) Conformist, establishment-approved art organizations get the most money, and she extends her rage to corporate greed, citing Coca Cola’s miserable actions in India that damage both humans and the environment.

The funding situation for dance here differs somewhat from that in Europe. It’s been many years since the National Endowment for the Arts gave grants to individual choreographers (including some for bold up-and-comers), and, at a time when Congress was—yet again—questioning the existence of the NEA and gearing up to slash funding, it was pointed out that the city of Frankfurt spent more money on the arts than the U.S. government. As Noworol may have discovered, kickstarter campaigns abound here these days. So we feel her pain without fully understanding the details.

Luckily, she keeps outright lecturing to a minimum, turning her grievances into a virtuosic vocal performance. Wearing flip-flops and a deep pink, chenille bathrobe, she climbs a ladder and yells and chants and growls words like “th-e-ah-ter” and “money,” railing against the situation of artists like herself and the evils of a particular German theater’s financial power structure. Noworol adds enough wit and self-deprecating asides to make complaints go down smoothly.

What’s remarkable is that all the time she is ranting, Seebacher is dancing. He has emerged from a place in the audience and, taking his chair with him, tried restlessly to position it successfully and stay seated. When she gets her steam up, he abandons the chair and responds with uncanny aptness to her vocal rhythms. This artist goes beyond popping and electric boogie; he’s a marvel of sinuosity, of tiny sharp articulations of, say, shoulders or hands against a rolling, undulating action in another body part; his feet move as if the floor were oiled.

As soon as this first bit ends, Brian Jones’s excellent lighting turns everything red, and Hallman does a multiple pirouette on his head. Some of the amped-up hip-hop music that accompanies parts of ?Culture kicks in. The music for the piece is uncredited (I thought I heard “Work It!”); that also goes for a section of deep, melodic, electronic fuzz. And the performers grunt and yell (Dougban, who is deaf, does some eloquent gesturing from time to time).

I’m not sure how to interpret two episodes. In one, Noworol appears in very short pants, high-heeled boots, and an open vest. Accompanied by loud music and glimpsed through the flashing of a strobe in dim light, she sheds the vest and, bare-breasted, hurls herself around. When the strobe cuts out, and the vest is put back on, she yells things like “conformist expectations” while furiously jumping on her knees. In the other scene, the five walk on in bizarre costumes and pose. Dougban wears outsized platform elf-shoes, a banana skirt, and a towering red wig. Hallman, bare-chested, is clad in what looks like the bottom half of a Victorian ball gown. Erdik sports a helmet and breastplate. Seebacher is concealed by a gas mask and leather-strip trousers (he has forgotten his jeweled collar, and Noworol goes back to the dressing room to fetch it). She has on what looks like a puffy mouse suit, minus the sleeves and head, but with a train cum tail. They all try to hold difficult positions or balances. If they fall, they start over. When they dance, they’re hobbled by their costumes.

I’m guessing what Noworol is suggesting in both these theatrical displays is that an artist has to cater to the public’s taste for sexually provocative displays and overdressed opera to be successful. The two scenes could also exemplify—in a backhanded way—a form of risk-taking on her part, although neither is profoundly risky.

What’s most gratifying about ?Culture is the skillful way Noworol structures the men’s moves, so that two dancing in unison can back up a soloist, or one slicing through space appears to comment on a textual consideration. For all its formal neatness and brain power, the piece is messy in its anger, its hitting out in several directions. But it packs a theatrical wallop even when it becomes almost incoherent. The five performers exude the electricity I mentioned through their skill, their discipline, and their camaraderie. You feel the jolt in your gut. Damn!