Tamar Rogoff’s Summer’s Different in La MaMa’s Ellen Stewart’s Theater, April 24 through May 12

Tamar Rogoff”s Summer’s Different. Foreground: Emily Pope-Blackman (L) and Deborah Gladstein. At back (L to R): Brandin Steffensen, Peter Schmitz, and Emma Lee. Photo: Julie Lemberger

A family’s summer day on the beach, what could be finer? Of course, someone might get sunburned, someone might drop her hot dog in the sand, someone might swim out a little too far. There could be bickering. Tears saltier than usual could be shed. But still. . .a cloudless sky, blue waves. That’s the kind of day it seems to be in Tamar Rogoff’s startling new work, Summer’s Different. When all its five characters are posed onstage at LaMama, they resemble the figures in some of Milet Andrejevic’s 1980s paintings of people at ease in Central Park. Updated from Greek legends, his still figures and their apparently pristine relationships suggest enigmatic, maybe darker underpinnings.

Rogoff prepares us for an idyll. The characters wear bathing suits, they spread towels; various garments hang from clotheslines at the end of the theater where the tiers of seating are usually filled with chairs. We spectators are arranged in a single U-shaped row that turns the performing area into an arena of sorts. The family members who enter one at a time are immediately identifiable. Peter Schmitz is the occasionally crabby grandfather, and Deborah Gladstein the mild, but not docile grandmother. Emily Pope-Blackman must be their daughter; she’s also the mother of a young teenager (Emma Lee) and a ten-year-old girl (Annabel Sexton-Daldry). The youngest child loves her father (Brandin Steffensen) very much. In fact, with some reservations, they all love one another.

Annabel Sexton-Daldry cartwheels for her family. (L to R) Peter Schmitz, Deborah Gladstein, Emma Lee, Emily Pope-Blackman. Photo: Julie Lemberger

Rogoff’s great gift (aside from her ability to choose and illuminate unusual scenarios) is her way of making small movements reveal large stories and large movements reflect emotional states, while bypassing display. As the characters enter, each takes a turn arranging a family tableau—gently leading others to a new spot and posing them, this one’s head on that one’s shoulder, someone’s arm around another’s waist. Another of Rogoff’s gifts is her compassion; it animates all her work.

In Beo Morales’s atmospheric score, music often gives way to the sounds of waves and gulls, sometimes of human voices (I thought I heard a coast guard’s announcement). Joe Levasseur’s lighting creates the weather—inner and outer. Everything seems quite normal at first. The family members do what you might expect—relax, put on and take off dark glasses, play. The little daughter dons a red kiddie tutu and dances around, gracefully waving her arms in the air; the others applaud her brave leaps in a circle. She and her father settle down to play. Both her mother and her older sister often take their long hair down or twist it back up into a bun, but the mother leans down and gestures, as if shading her eyes or looking under something. Grandmother basks in the sun. Grandfather takes off his specs, points them down, and peers, as if they could magnify beach life.

The family members travel to new stations along the edges of the semi-circle and repeat their actions during the course of the dance. They scan new territory; we get new perspectives—the unself-conscious beauty of the older daughter, say, and her awareness of her recently changed body; her grandfather’s protectiveness of her; his stiff, obligatory push-ups.

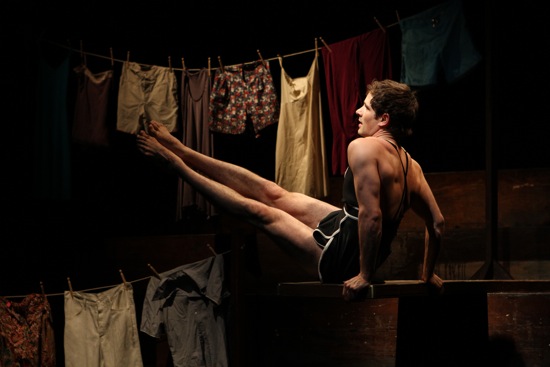

They all, at one time or another, scan an apparently cloudless sky. It is, therefore, a shock when Steffensen appears on what seems to be a diving board jutting out from the bleachers; he’s wearing a rather old-fashioned woman’s bathing suit. The board is a liminal place, and this is his moment of decision, a private revelation. The others are asleep, and he is lit as if he’s alone on a cliff in a shaft of light. That light goes briefly out. Now you recall how adept he was at putting makeup on Sexton-Daldry (at her request). How when the girls wrapped their supposedly wet hair in towels, he created a more elaborately twisted turban out of his towel. You remember, too, how often he simply watched Pope-Blackman.

Delicately, Rogoff and the performers dissect what must inevitably ensue when an apparently straight man, a loving husband and father, feels himself to be—in a crucial part of his nature—female. Transgender identification can manifest itself in various ways, and Rogoff doesn’t attempt to analyze the man’s situation in detail. Instead, she shows us his anguish and how—in a kind of shame perhaps—he retreats from his wife. In a beautifully conceived sequence, Steffensen (he has removed the bathing suit) walks, then runs faster and faster in a circle. Pope-Blackman pursues him. She wants to touch him—perhaps to console him, perhaps to reassure herself that he loves her, perhaps to question him. Maybe all three. He shrugs away from her hand, pushes her back. They run and run and run; eventually they become violent.

Something is gradually achieved in the couple’s moments of rueful tenderness (underscored by sweetly sentimental music), but the family’s equilibrium has been upset, even though all return to some of their earlier separate activities, The grandfather, apparently appalled, doesn’t want the girls to see what’s happening to their parents and keeps shoving his son-in-law away; his wife calms him. She also soothes the teenager, who is more upset than her little sister (she loves her father and doesn’t see a problem).

Rogoff has chosen to make items of clothing symbolic of the deeper changes, perhaps because cross-dressing as a phenomenon is readily apparent and understood. When Pope-Blackman performs a furiously conflicted solo, hurling and twisting herself around, she’s wearing a slip. (Schmitz and Gladstein pass through, fond and at peace, appearing not to see her distress or hear her gasping for breath.) When she has finished, Steffesen appears, and she takes the slip off and hands it to him, backing away, covering her breasts with her arms as if she has never felt so naked in her life. Lee brings her a towel, wraps her in it, and leads her away.

Now we see what the man has been wanting. Steffensen conveys with wonderful sensitivity how the slip makes him feel. It’s like a new skin, something he can subtly undulate into and against. He raises his arms softly, calling to mind the little girl’s lovely freedom of movement. She is coltish because of her youth; he is awkward because he’s young in a different life.

The matronly bathing suit has another role to play. After we see new manifestations of the tensions and alliances within the group. Gladstein brings the garment and hands it to Steffensen. It’s a somewhat corny moment, theatrically speaking, but it makes an unequivocal point about forgiveness, and it isn’t dwelt on. In an echo of the beginning, Lee repositions Pope-Blackman and Steffensen, allowing them unity with each other, as well as with Gladstein and Sexton-Daldry. She herself keeps hold of Sexton-Daldry’s hand, but steps away, staring into the distance. Schmitz, still troubled, stands completely apart from the group, staring at a picture he finds difficult to understand and accept, even though it’s composed of people that he loves.

As I write this, I’m aware of moving back and forth between the names of the characters and the names of the performers who bring them to life. As a writer, I want readers to keep the characters straight, but I also want to convey how sensitively and carefully these performers inhabit their roles. You almost feel that you could go up to any one of them and pay after-show compliments, but just as easily ask, “So how do you feel now about all that happened today on the shore?”

beautifully written. appreciation for close viewing! AO