(L to R) Antonio Brown, Talli Jackson, and I-Ling Liu of the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company, Photo: Lois Greenfield

Bill T. Jones is a taking a holiday from the spoken word. The last time he did that may have been in 1992. Unlike his Serenade/The Proposition (2008), Fondly Do We Hope…Fervently Do We Pray (2009), and Story/Time (2011), none of those on view during the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company’s season at the Joyce Theater (March 26 through April 7) makes use of text. None of them presents a view of current political or social injustices. All but one are set to the works of major dead composers that Jones reveres, and Beethoven figures importantly in Jerome Begin’s new score for Continuous Replay (Jones, 1991; from Zane’s Hand Dance, 1977). Audiences for these programs are fortunate to be able to hear the music played live by the Orion String Quartet (Daniel Phillips, violin; Todd Phillips, violin; Steven Tenenbaum, viola; Timothy Eddy, cello).

As one who is gearing up to direct and choreograph Super Fly for Broadway, Jones evidently needed to take a deep, quiet breath. Watching five of his works, spread over two programs, you get a strong sense of what matters to him, and of how he stitches his values and his delights into his choreography. Jones loves beautiful bodies in motion—arduous, full-spirited motion, but he also has reverence for those that are older or stouter or less nimble, as evidenced by the naked multitude you may remember in the final section of his 1994 Last Supper at Uncle’s Tom’s Cabin/ The Promised Land, and the former company members who appear as guest artists in Continuous Replay at the Joyce. He likes smart, powerful dancers who don’t fit a mold, and he makes use of their individuality. The two most recent works on the programs, Ravel: Landscape or Portrait? and Story/, credit the choreography to Bill T. Jones “with Janet Wong and the Company.”

(L to R): Antonio Brown. LaMichael Leonard, Jr., and Erick Montes Chavero in Bill T. Jones’s Story/. Photo: Paul B. Goode

Community matters to him. In every work seen at the Joyce, the superb performers are aware of one another—whether during some passages or all the time. They are quick to catch a colleague about to fall, or to pull upright one who has collapsed. They’re good at assists—two people, say, adroitly and nonchalantly, helping one person to jump over a third. The fluid complications that arise when four or five dancers merge in a push-pull, duck-under, loop-around group are not only arresting to watch; they embody an ideal of peaceful, but muscular cooperation.

Dancers flock, herd, gather force, form chains; they may travel along together as a group, even though everyone in the group is moving differently. D-Man in the Waters (1989), Ravel, and Story/ all begin (or nearly begin) with the performers clustered in one of the stage’s far corners to voyage forward along a diagonal together, perhaps breaking out of the group, perhaps not, and sometimes (as in Ravel) retreating to the corner to begin again. In D-Man, people at the rear of the group, over and over, rush to the front; the image of a breaking wave is accompanied by one of constantly—and peacefully— changing leadership.

Jones has had a long love affair with repetition. He likes to have certain passages recur, perhaps slightly transformed (the music, of course, summons him with its own repetitions). This happens not only within a dance, but among dances. In an interview with Robert Johnson of The Star-Ledger, Jones said that over more than 30 years spent making dances for the company, he has acquired a lot of “choreographic real estate” that he can draw on and “recontextualize.” He acknowledges in the Playbill program that he based the third movement of his 2012 Ravel: Landscape or Portrait? (a New York premiere) on a study by former company member Eric Bradley.

He borrows from himself and—directly or indirectly— from his partner Arnie Zane, who died in 1988. In D-Man, the dancers sometimes flutter their forearms rapidly in front of their faces; the gesture has a family resemblance to a single one performed sharply, with an accompanying vocal hiss, in the accumulating phrase that Zane constructed and performed in Continuous Replay (1977). When I watch Jennifer Nugent crossing the front of the stage with a calm, deliberate, tiptoe walk in Ravel: Landscape or Portrait?, I flash back to a similar journey made by the whole company in the second movement of D-Man in the Waters, and it’s a surprise when Nugent breaks the pattern by going up to Erick Montes Chavero, as he twists himself around in a patch of light, and whispering something in his ear.

The company in Bill T. Jones’s Ravel: Landscape or Portrait? Antonio Brown jumping. Photo: Paul B/ Goode

Jones has favorite steps too. The dancer shoots into a jump, legs together, arms usually winging high. He/she somersaults, lunges, sweeps one leg out as a lever to induce a turn, spins in a modified pirouette (this last is my least favorite). The marvelous company members grasp in their own ways the boldness of Jones’s style—its groundedness, its space-devouring steps, and—by contrast—its small, finicky gestures. They’re adept at the sinuous, controlled muscularity that causes shoulders to roll, arms to snake, hips to sway—often all at once. Nothing looks lazy or completely fly-away. Death-defying moves are in the cards. These are heroes.

The compositional strategies give logic to the beauty. Spent Days begins with three dancers (Talli Jackson, Shayla-Vie Jenkins, and LaMichael Leonard, Jr.) moving quietly with their backs to the audience (I’m reminded that Jones once performed Trisha Brown’s solo If You Couldn’t See Me in a duet version; she remained turned toward the back of the stage the entire time). The music is the Andante from Mozart’s String Quartet No. 23 in F Major, and Liz Prince’s lightweight costumes flow softly.

Spent Days Out Yonder: LaMichael Leonard, Jr. (foreground); at back, Joseph Poulson holding Erick Montes Chavero. Photo: Paul B. Goode

Jones has built a long, long river of movement to this ravishing music written by Mozart a year before his death. Just as the composer embellishes and twists his opening passage, the choreographer develops the phrase that begins with the three dancers moving only their arms and gradually expands to involve other parts of the body, to take up a little more space, to encompass changes of direction, jumps, and a denser texture. Mozart passes his melody among the stringed instruments; Jones sets up a process of replacement; people entering to join the phrase, leaving it at various times. Maybe it will be Antonio Brown, Erick Montes Chavero, and Jenna Riegel whom you see feeding in. Maybe Nugent or I-Ling Liu or Joseph Poulson. Sometimes three people keep the phrase going, sometimes more. Small skirmishes occur intermittently behind the main event, parades cross in front of it. At the end, the musicians have to prolong their last note while the dancers exit in a slow, pouring cauldron of movement, but that’s a small flaw in a dance that I’m falling in love with.

Continuous Replay also accumulates, grows, and diminishes, but it looks nothing like Spent Days Out Yonder. In his original, rigorous solo, Zane was perhaps paying homage to Trisha Brown’s Accumulation (1971) and her subsequent related works. Montes Chavero begins the process alone (he shares the role of “The Clock” with Riegel), building the sequence of precise gestures and moves, returning to the first after each new addition as he slowly traverses the width of the stage, comes toward the audience, and turns to progress across the front. The dancers who feed in and out of the phrase begin naked, as does Montes Chavero, but unlike him they add items of apparel—first black, later white. Jones has added other events as well as people—having some performers simply run through at times, giving others fancy entrances, and creating another dance off to the side, in which, for a while, the beautifully fluid Liu starts stretching her limbs into space, balancing on one leg, and attracting others to her private party.

For those familiar with Jones/Zane history, there’s another kind of party going on. On March 26, we could pick out Arthur Aviles, Dwayne Brown, Catherine Cabeen, Seán Curran, Lawrence Goldhuber, Ayo Jackson, and Colleen Thomas in the advancing horde. The Orion Quartet plus string players Aaron Boyd, Molly Carr, Pauline Kim Harris, and Julia MacLaine gallantly merge elements of Beethoven’s String Quartets Op. 18, No. 1 and Op. 135 with recorded sounds in Begin’s Music for Octet.

Joseph Poulson carries Jenna Riegel in D-Man in the Waters. At back: LaMichael Leonard, Jr. and Antonio Brown (obscured). Photo: Paul B. Goode

Eight players are also needed for D-Man in the Waters, since it’s set to Felix Mendelssohn’s Octet for Strings in E-flat major, Op. 20 (1825). The work premiered in 1989, when company member Demian Acquavella was swimming against a powerful current: AIDS. Jones and the other dancers were honoring his gallant ongoing struggle, which was to end in 1990. At the last performance of that 1989 season, granting Acquavella’s wish, Jones carried him, costumed, onstage and the others bore him through parts of the choreography. As Jones said, taking a bow at the end of opening night at the Joyce , “There are ghosts in this dance.”

The current Jones-Zane company members would have been toddlers or unborn when D-Man premiered, but they dance it as if to stint its hurtling energy would be unthinkable. The choreography builds on the turbulent water imagery and captures the ferocity of Mendelssohn’s music. This is a celebration of vigor and the will to survive, not a presentiment of loss, although several times a single performer vaults toward another and clamps on, to be carried away, and in one brief section, Jackson stands in the middle of a square made up of the company’s four women and interrupts his dancing in time to catch each of them as she crumples.

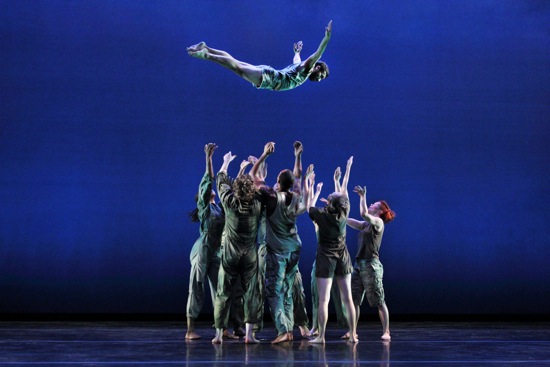

Most of the time, however, the dancers—clad in Prince’s guerrilla-warfare clothes—leap exultantly through space in a multitude of ways, dive, slide on their bellies, somersault, roll, swim. Occasionally, in the background, two people struggle together; one of them trying to move forward, the other holding him or her back. They form chains that whip around the space. It’s a gorgeous, valiant killer of a dance about not dying. Montes Chavero is tossed high by the group, and the stage goes dark while he’s still in the air.

Both the newest dances have décor by Bjorn Amelan, as well as the splendid lighting by Robert Wierzel that graces all the works. For Ravel: Landscape or Portrait?, the stage is enclosed by the slimmest suggestion of a room—a rope cube whose boundaries are delineated by corner verticals, with horizontals connecting them on the floor and overhead. Story/ takes place on a grid of white lines, four rectangles wide by three deep, and the members of the Orion Quartet are seated upstage left.

Ravel: Landscape or Portrait? Erick Montes Chavero (lifted) and (L to R): Talli Jackson, LaMichael Leonard, Jr., I-Ling Liu, Jennifer Nugent, Jenna Riegel (in front), Antonio Brown, Shayla La-Vie Jenkins. Photo: Paul B. Goode

Ravel is set to Maurice Ravel’s 1904 String Quartet in F Major. The dance, echoing its moody impressionism, is less legible than the other works and as enigmatic as its title. Apparently, Jones has created two variations for the third movement, but I can’t tell whether I’m seeing “Landscape” or “Portrait.” While the group waits in a corner, Montes Chavero faces them and touches the floor in ways that suggest he believes it to be earth—his terrain. The dance begins; then the group retreats to its corner and starts over. For a moment, Montes Chavero looks straight at the audience, as if recruiting out attention. We see the expected breakouts from the group, the coalescing again. The other three women and Brown dance to a pizzicato passage. Often the performers—wearing a playful array of outfits—freeze in mid-action. In this dance, they’re especially watchful of one another in this.

Boundaries become important (what’s inside, what’s outside); crossing them, while not dramatized, becomes a choreographic issue. And in one stunning visual effect, a projection of dark foliage on a white surface, fills the back wall and floor of the stage and then spills out to turn the entire wall of the theater into a leafy grove for Nugent—as supply muscular as a cat—to inhabit. The dance ends as it began, with Montes Chavero alone. Could he be rolling dice?

Story/ grew out of Story/Time (2012). In the earlier work, Jones, seated onstage read 70 one-minute autobiographical stories, while the dancers’ movements coincided with them, or didn’t. He was inspired by a similar process of John Cage’s, as well as various Cagean ideas about indeterminacy. There are no stories told in Story/—at least, not in words. Jones also allowed the Orion Quartet to choose the music for the dance from a list; he, Wong, and the dancers then created what the program calls “a random menu of movements” that could converse with that score. The musicians chose Franz Schubert’s String Quartet No. 14 in D Minor (Death and the Maiden).

The choreography is very eventful—meaning event-full. Now the dancers are moving into poses, freezing, moving again. Now they’re in a corner, yelling in unison before advancing in slow motion along a diagonal. Montes Chavero enters with a round object (maybe one of the green apples from Story/Time), which he occasionally holds while dancing, or tosses. Nugent and Poulson have a brief silent dialogue, pointing their fingers in various directions. Riegel rolls across the stage, dispensing smoke from a gadget attached to her legs.

All kinds of vivid trios, duets, and quartets surface and disappear—some within seconds. Orderly formations materialize and erase themselves. One of my favorite moments occurs when two different quartets, performed in place, coexist on the stage and, just in case you couldn’t grasp the intricacy at first, generously repeat their intricate maneuvers. A few words invade the conversations that the performers are having with Schubert. In a group phrase at the end, one or another of them calls out “ready” and “reverse” to cue the choreographic possibilities. But for all the contrasting vignettes and the grid that organizes the game plan, the piece flows along remarkably amicably with the beautiful quartet, and death hides itself very successfully in vibrant life.

A BILL. T/jones:

Felicidades por su gran compañia y su talento me siento muy emocionada de conocer su trabajo reciba un afectuoso saludo de su admiradora y ojala que pronto lo pueda saludar personalmen te.

atte

irma chavero rosas