Souleyman Badolo and Cynthia Oliver at New York Live Arts, April 25 through 27

At one point in Suleymane Badolo’s new solo, Barack, on the opening night of his season at New York Live Arts, Badolo dances with his back to the audience, clapping his hands together vigorously; when he stops, from the audience comes a small-voiced echo of his action (maybe two pairs of hands clapping) that extends the sound for a few seconds more. When Badolo turns and begins backing up in a curving path, he directs a sweet grin in the direction of the spectators who were so caught up in his rhythm. Somewhat later, he approaches a few people in the front row and walks part way up one aisle—rippling his arms for one spectator, shaking another’s hand, swinging his hips at another.

In both Barack and Buudou, BADOO, BADOLO, this wonderfully compelling dancer-choreographer performs for the most part introspectively—listening to his body, consulting his memories. But he never seems entirely alone; a virtual village surrounds him. Perhaps one in his native Burkina Faso, perhaps the community he’s part of in New York, where he moved in 2009. Barack is not about our president, NYLA’s press release informs me; the word means something like “gratitude” in Gurunsi, the language spoken by members of Badolo’s ethnic group in southern Burkina Faso. I also learn that the dance expresses his thanks to those who have helped him in his new home here.

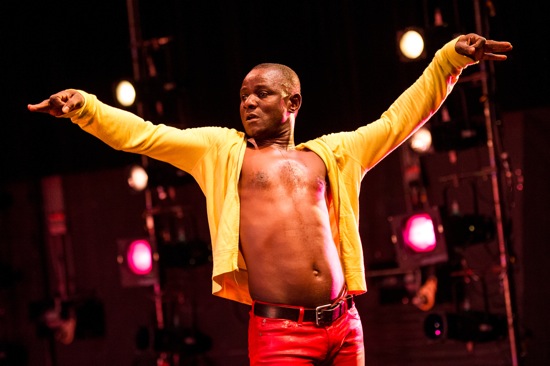

I didn’t read that information before seeing the dance, so I had nothing to peruse but his movements and rhythms. Only now can I link to its theme his proud bearing and the slightly stiff, ceremonious bows he makes in different directions. These formal acknowledgments are in interesting opposition to his attire: belted red pants and a yellow hoodie, unzipped to show his bare chest (costume: Nora Chipaumire). The music is a surprise too, unless you recall that Burkina Faso was a French colony until 1960. While Badolo tests his joints—rippling his arms until his shoulders and elbows move like freshly oiled mechanisms—the inimitable recorded voice of Edith Piaf begins to sing “Non, je ne regrette rien.” Maybe Badolo chose the song (which plays twice during the dance) less for its language than for its meaning. Piaf has no further use for her sorrows or her pleasures; she has swept them away and “I begin again at zero.” Her life starts today “with you.”

Badolo stays in one spot, while his arms churn his body and his planted feet into complex motion. He doesn’t escalate in intensity as Piaf does, but he seems to expand in space—his feet edging farther apart, his knees bending more deeply. The solo is full of pauses and new ideas. Sometimes, Badolo rounds his arms as if embracing air; sometimes a pressure from above bends him backward. His balances on one leg seem precarious, uneasy. When Piaf sings again, he moves more slowly, rubbing his hands over his body, wiping something away. “Can I try this?” he seems to be asking himself. “Does this fit?” New music accompanies him; this time it’s by Tabu Ley Rochereau, the Congolese singer-composer (and politician), who mixes musical elements from other cultures into his native music. The lighting, designed by Bill Schaffner and Badolo becomes a veritable rainbow of colors.

I don’t mean to make the action sound static. Badolo draws on African styles. He moves with elegance and great resilience. His feet skate over the floor; his pelvis undulates; his knees lift high; his shoulders circle. When he spreads his arms, he resembles a hovering bird. When he explodes into the air suddenly, as he does at times during Buudou, BADOU, BADOLO, his limbs seem to flash out from his body, and you wonder if he can collect them again before his feet have to hit the ground.

In BBB, Badolo channels his great-great-grandfather and the roads he traveled in search of help in fathering children. By extension, the piece expresses not only the ineradicable tapestry of ancestry, but Badolo’s own artistic searches; he has likened his throwing of the little cowrie shells, which traditionally divines future life strategies, to John Cage’s tossing coins to derive compositional structure from the hexagrams of the I-Ching.

This piece centers on four objects set upon the floor; they represent methods of divination. Alleyways of light lead to the zones they control (Badolo and Schaffner credit the original lighting design to Rick Martin). The first object is a mound of what appears to be dirt. Badolo gropes his way to it and kneels. As with the other “shrines,” he begins by bending over to lay the back of his hand and then his palm on the floor. His actions at each station are forthright and functional. In this rite, he fills his mouth with water from a cup and sprays it with great force over the mound; by the time he has finished, he has uncovered something, although I can’t tell what it is. Periodically he bursts into the air.

He jitters expansively while approaching the second ritual object—a flat, square containing what could be sand, but which I believe is rice. This is no easy process, whatever he hopes to gain from it. He stabs his index finger into the substance, as if writing something, rubs it out, starts again, stands up and staggers backward, returns to his task. He jabs the surface with both fingers. Only now does Mamadou Konate, the musician seated in dim light at the back of the stage, begin to play—quietly— his collection of percussion instruments.

Badolo drops to his knees in one swift move when he reaches the tray containing the small white shells. He gathers them up and tosses them out, then scans them, pointing, saying something in his native tongue. Konate responds with a word or two. The terse conversation continues as Badolo throws again. Once, a single shell lands outside the tray; that seems important and conclusive. Konate, shouldering a small drum, follows Badolo around the now brightly lit stage; recorded guitar music (by Ben Broderick Phillips) and the sounds of excited voices and other city noises accompany this last dancing journey.

Another object becomes visible, off to the side and closer to the audience. After executing an enormous jump, Badolo inverts a small metal basin onto his head; this “helmet” oozes a white substance that he spreads over his face and hands. He’s standing there thus transformed as the lights fade. I have no sure idea about the meaning of this, but I’ve seen photographs of rituals in various African countries that use white face paint in ritual performances. Perhaps this was the final rite of his ancestor’s quest. Perhaps it’s only another beginning. If the lights hadn’t gone out, I might never have been able to take my eyes off him.

It’s not crystal clear why Cynthia Oliver’s 17-minute BOOM! was presented as a kind of curtain raiser for Badolo’s two solos (it’s part of a longer work to come). Perhaps it was chosen because Oliver (performer, choreographer, teacher, and scholar) is dealing in her own way with personal and cultural history. The piece is intriguing from the outset. The argumentative voices of two women come from behind the audience; they sound like irate grandmothers. Neither of them pauses to let the other speak, as they squabble their way down the steps and into the performing area and Amanda Ringger’s lighting. They turn out to be Oliver and Leslie Cuyjet, both wearing loosely-cut white tops and colorful pants. The first thing these two fascinating women do is strike poses and check, in words and gestures, their physical dimensions and what parts of their bodies they don’t like so much. Again, they talk over each other. Drums start galloping in Jason Finkelman’s recorded score.

Although over the course of the duet, Oliver and Cuyjet occasionally talk in a relaxed way or walk matter-of-factly to a new area, that may be just postmodern trimming. I’m coming to sense something that’s corroborated by the press release: much of the time, the two dancers are expressing aspects of a single person. This is easy to do in movies, harder to convey in dance. How does one perform an “aspect,” when the audience clearly sees two people?

Nonetheless, Oliver’s strategies yield some engaging, humorous, and highly theatrical events that support her theme in various ways. She shows us the two women in near perfect synchrony—covering a lot of territory, swiping gestures onto the air, pumping their butts energetically. They also have their divergent moments. Sometimes they wander about, gazing here and there, as if they’ve lost track of each other, or of whatever they’re after. They may separate and dance on opposite sides of the stage and then be pulled together by some unseen bond. For some time, they stand in a close embrace, changing positions or grips to become even more of a single entity. The fact that they don’t look alike and that each is beautiful in her own way adds to the power of their relationship. Finkelman’s music molds excellently to their changes of mood.

At the end, their joint self-image comes in for some serious pummeling. Crawling into a seated position, side by side and close to the audience, they start to talk. Their vocal unison is as impressive as their dancing one. “I’m a punish you!” starts a string of insults, including “I’m a turn you inside out!” that could have come from deep inside a childhood memory. Since they’re staring at the spectators and spitting the words at us, we might at first think we’re the enemy. But no. This is self-hatred, followed by self-love, followed by more threats and insults. The litany suggests it’s trailing a history we don’t yet comprehend. Finally, temporary harmony ensues between these conflicting selves. The two finish with “I’m going to embrace you, grace you, and set you free.” I’m crossing my fingers. And looking forward to the expanded work.