Can one refer to someone as a perpetual dark horse, or is that a contradiction? If not, I’d like to apply it to Paul Taylor. You can never predict what he’ll come up with, or what thumbscrews he’ll apply to his essentially buoyant vocabulary of steps. Among the 21 works on view during the Paul Taylor Dance Company’s three-week season at Lincoln Center, some, such as Speaking in Tongues, are big and tormented; others are nightmarish, e.g. Last Look. Some are ineffably tender and mellow like Eventide; others are tart and joke-filled like Offenbach Overtures. And that’s just a hint of what this master can do in the way of twining the beautiful with the ugly, sunshine with shadows, the rich with the austere, the enigmatic with the crystal clear.

Several dances are celebrating birthdays. 2013 marks the 25th anniversary of Brandenburgs and Speaking in Tongues, the 50th anniversary of Scudorama, and the 100th anniversary of the Stravinsky-Nijinsky ballet that lent its name—and more—to Le Sacre du Printemps (The Rehearsal). Two are just being baptized.

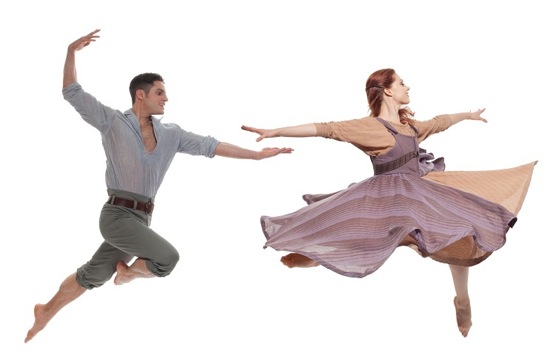

The new Perpetual Dawn explains its title by offering lines by Emily Dickinson as a program note: “No seasons were to us—/It was not night nor noon,/For sunrise stopped upon the place/And fastened it in dawn.” Taylor must have fixed on the notion of dawn as an endless wooing between the time love starts to bloom and its consummation. James F. Ingalls lights Santo Loquasto’s painted backdrop of fields and hills in a rosy haze, then turns the clock back to a pre-dawn bluishness, and finally intensifies the original sunrise. Through this landscape, would-be lovers pursue one another to recorded music drawn from the Dresden Concerti of J.S. Bach’s contemporary Johann David Heinichen. The tempi are almost all brisk, the mood spirited.

Loquasto’ costumes suggest a dressed-up version of peasant attire—not just what country folk would be wearing after the haying’s done. The dresses and overdresses worn by the five women look as if they were made of silk and billow charmingly in the wake of their chases and flights. Taylor’s bucolic romp rarely calms down. In the stillest moment, the women look around expectantly and try out some poses; they put their hands on their hips, but don’t appear exasperated by the momentary absence of the men. There’s a pantomimed argument (or guessing game?) between Amy Young and Heather McGinley (I detected an allusion to a fish). One shoves the other, but they’re still friends. When no women are around, Francisco Graciano dances with the shyer Michael Novak; they take hands when they’ve finished. Michael Trusnovec and Young move around happily in ¾ time and throw in some rambunctious somersaults.

No one is alone for long, and there is much changing of partners. All the dancers (including James Samson, Michelle Fleet, Sean Mahoney, Eran Bugge, Laura Halzack, and Michael Apuzzo) fly past—running, leaping, spinning—in continuous motion, with the occasional kiss or capture or rest before they dash away again in pursuit of whoever lures them on. At the end of Perpetual Dawn, the dancers gather in a circle for a mazy folk dance; they’re still going round and round when the curtain falls. There are no snakes in this Arcadia. Neither are there shadows.

To Make Crops Grow, the other new work in this bountiful season, is single-minded in a different way, and much scarier. It was sly of Taylor to schedule its debut on the same program—and just before—his strange and fascinating Le Sacre du Printemps (The Rehearsal) from 1980. In terms of theme, this new dance, too, refers to the controversial masterpiece that Igor Stravinsky and Vaslav Nijinsky created for Diaghilev’s Les Ballets Russes in 1913. Like Taylor’s House of Joy last season, To Make Crops Grow relies more on behavior and pantomime than on dancing to get its story across. Perhaps to fool us, Taylor establishes a small-town community of people who might have stepped out of Thornton Wilder’s Our Town, but doesn’t develop them in much depth. A couple identified as “needy” (McGinley and Samson) have a spunky little son and daughter (Jamie Rae Walker and Graciano); the boy mischievously yanks at one of the red hair ribbons worn by their playmate (Aileen Roehl). Her parents are clearly better off. Parisa Khobdeh wears a silky dress and a cloche and acts uppity; Apuzzo, his stomach padded, sports a white summer suit and straw hat. Bugge and Mahoney play newlyweds.

But those objects lying about the stage aren’t melons waiting to be picked. They are big stones, and when the kids have done with their horseplay (to excerpts from that American classic, Ferde Grofé’s Grand Canyon Suite), they lug them with difficulty and arrange them in a corner.

Grofé’s music was written during the early days of the Depression, and it’s that period that Loquasto’s costumes, Ingall’s prairie-sky lighting, and the mood suggest. The church supper we might be expecting isn’t what’s coming, however. In walk Robert Kleinendorst and an assistant (George Smallwood), bearing a black box that they set on a stool. Everyone gathers expectantly. Kleinendorst dons an extraordinary headpiece. From the front, it looks like a loose-fitting, gilded Prussian helmet; seen from the rear, a black mane, somewhat like that of an Indian Kathakali dancer, hangs down. Is this man perhaps a snake-oil salesman visiting the village? He reaches into the box, pulls out a piece of paper and shows it to them (this is a demonstration). Oh. A lottery.

It gradually becomes clear from the folks’ behavior that this is not a lottery in which one person wins, and everyone else loses. The fear of picking the crucial paper, the smiles of joy or relief reveal that the opposite is true. So does the loving duet that McGinley and Samson have after they’ve both taken their turns. Remember Shirley Jackson’s short story “The Lottery?” Taylor must have read that chilling tale of how apparently “nice” people can conform to the unthinkable and make vicious murder a desirable ritual, even if it may require husbands to turn against wives and children against parents.

Think back to the title: To Make Crops Grow. In this dance of Taylor’s, as in the original Le Sacre du Printemps, someone must be sacrificed, or spring and prosperity will not return. The elegant young woman draws the fatal piece of paper. Her husband turns his back on her. Almost instantly, Khobdeh is running for her life. Off come her shoes, down comes her hair; the mob chases her, the men drag her, writhing, to where the children have cheerfully placed the stones. Crumpled papers suggesting a history of such rites blow along the floor. The entire community pens her in; everyone lifts a rock overhead, and just before the curtain falls, the stones are pressed forcefully, silently, down.

At the first performance, the ending wasn’t as fiercely dramatic as it could have been, although the very haste with which this very small group turns on its chosen victim makes the whole business seem even more ghastly. Here’s a terrible footnote to Taylor’s work. When Jackson’s story was published in the New Yorker in 1948, it elicited a barrage of questions and criticism in the form of letters and phone calls to the magazine. She later recalled that “People at first were not so much concerned with what the story meant; what they wanted to know was where these lotteries were held, and whether they could go there and watch.”

Taylor’s dancers are marvels at animating everything they do—whether that’s juicy dancing or the acting that’s called for in pieces like To Make Crops Grow. After the nasty clarity of the new work, Sacre is a veritable grab-bag of puzzling, thought-provoking complexities. Interestingly, the people in Crops seem like real apple-pie-on-the-windowsill folks, yet don’t become fully three-dimensional. The cast members of Sacre, on the other hand, maintain the kind of flattened, two-dimensional body positions that Nijinsky favored in his Afternoon of a Faun and behave with stylized single-mindedness, yet you feel complicated emotions hovering.

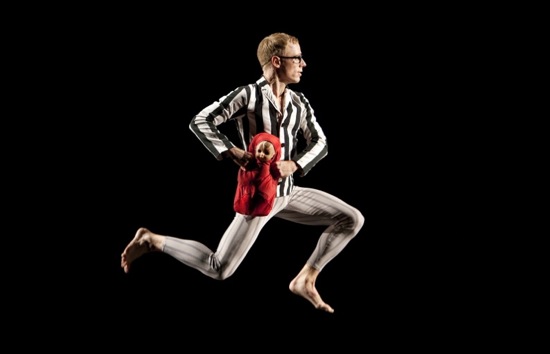

The choreographer interweaves three layers: a rehearsal of gray-clad dancers led by a severe woman in Cossack attire (McGinley); a crime story styled like a silent, black-and-white Hollywood two-reeler (set and costumes by John Rawlings); and, somewhere underneath, the sacrificial-victim rite that Stravinsky depicted in his music. The tremendous score, heard in the four-handed piano version to which Nijinsky and the Ballets Russes dancers rehearsed, reinforces all three layers.

Confined by their two-dimensionality, the performers hop or prance or march or strut across the stage in horizontal slots, occasionally doubling or shadowing one another, until you can’t be sure what the rehearsal is for—the comically presented crime story, the dark rite behind it, or both. The plot moves along with frequent freezes and occasional blackouts. The nice, bespectacled Private Eye (Trusnovec) is somehow framed for the theft of a handbag full of jewels and jailed just after his Girl (Halzack) has presented him with a baby (a red bundle—the handbag and the baby are the only colored items onstage). The real Crook (Kleinendorst) has a Mistress (Young in a black wig as an Asian) who works in a bar; she steals the baby. When she turns down the jewels the Crook offers her from the bag and sits at her dressing table dandling the infant, he sees red in another more dangerous way and orders his Stooge (played by Walker, one of the smallest women in the company) to kill the baby.

The layers intersect in mysterious ways. When the Rehearsal Mistress, perched on a tall ladder, is tipped from side to side to dole out pay to the rehearsing dancers, Mahoney steals Halzack’s money . Her fight with him is duplicated behind a scrim by the gangsters and girls. The Mistress’s dressing table has a see-through mirror, and her gestures are copied (or vice versa) by the Rehearsal Mistress. I spoke of silent movies, but at times, the characters move more like clockwork figures. Sometimes the men whirl the women in the air in front of them as if they were manning big wheels.

There are more roles than dancers to fill them. Fleet, Khobdeh, and Bugge play Bar Girls, while Mahoney, Apuzzo, and Novak have to double as Policmen and Henchmen (all it takes to transform them is a change of hats). Still, in the final cartoonish struggle with large cardboard knives, the pileup of bodies seems very large. The Private Eye has saved the stolen infant, but when the Stooge, too nice to kill it, stabs herself instead, her arm flies up in a reflex action, and bye-bye Baby. So the bereft Girl, surrounded by Stravinsky’s urgent music for the Sacrificial Dance, is, for a few minutes, the only one left alive, mourning amid a sea of gray bodies that perhaps represents the dancers, who sacrifice themselves to art on a daily basis. Did I say the only one alive? The Rehearsal Mistress is still there, holding up the red-bundle, as if to offer the choreographer a newborn idea that he’d better get working on.

Both the new pieces premiered on programs that included Three Epitaphs (1956) and Junction (1961). These show the young Paul Taylor at his most wildly inventive. What choreographer but he could have come up with a dance like the first, in which five performers slump along with dispirited precision to a recording of early New Orleans funeral music? They stand up straight and whirl their forearms; the tallest man in the bunch (Taylor in 1956) shuffles along, knees bent, chest and butt out. But the whining and blaring of the proto-jazz band, along with its heavy, thudding rhythms, inevitably causes them to slouch and sometimes to fling both forearms down to one side, as if emitting a big, resigned sigh. The costumes that Robert Rauschenberg designed are as imaginative as the dance. Completely covered in brownish mauve outfits with mirrors sparkling on them here and there, the dancers resemble members of some prehistoric tribe with fully recognizable habits. The smallest one (Eran Bugge) tags along behind the tallest (James Samson); he doesn’t always appreciate this. The others (Graciano, Halzack, and McGinley) perform moves that suggest two friends comforting a widow—repeating the pattern over and over until it takes them across the stage and out of sight.

Junction also has wonderful costumes (by Alex Katz); they turn the dancers into latter-day harlequins, their unitards elegantly divided into patches of brilliant color (made even brighter by Jennifer Tipton’s exemplary lighting). In 1961, two lengths of red cloth formed an x on the floor during part of the dance; that “junction” is gone now, leaving the junction—or disjunction—as the one between the choreography and excerpts from two of J.S. Bach’s Solo Suites for Cello. The eight dancers sometimes move rapidly to slow music and vice versa, and their dignified walks—suitable for entering and leaving an 18th-century court—connect with crazed, sometimes animalistic or clownish behavior.

Taylor’s Junction. L to R: Parisa Khobdeh, Robert Kleinendorst, Jamie Rae Walker on Michael Novak, Sean Mahoney. Photo: Paul B. Goode

Many images in Junction suggest the animal kingdom, beginning with the opening picture: Walker squats froglike and immobile for a very long time on a human mound (Novak, kneeling and bent over, is unidentifiable at first). Mahoney bursts into fits of dancing as if he’s swatting away a swarm of insects (or ideas). At one time or another, performers hunker down and wheel their straight arms from the shoulders like bees inspecting a tasty plant; they shoot up in bent-legged jumps and curve their arms in ways that also call up images of predatory birds settling over their prey. They squabble too; one person’s aggressive gesture can affect someone standing a foot away.

You may think you’re watching a bunch of zany acrobats or a colony of bright-colored tropical creatures, but after Walker has finally arisen from her opening pose, Mahoney lifts her up and sets her on his shoulder. Enthroned there, she gazes into the distance—serious, calm, ready for anything. At a measured pace, he carries her offstage. For a moment, the craziness drains away.

Taylor is a master of animal behavior (think of Cloven Kingdom, Book of Beasts, and more). He’s also expert at turning it into comedy. As soon as you hear the thudding drum-rolls that usher in Jacques Offenbach’s La Grande-Duchesse de Gerolstein Overture and before the curtain rises, you can anticipate with joy what Taylor heard in the composer’s roistering music: parading soldiers with an eye for the women, can-can girls, mysterious lovers in black (Halzack and Smallwood). In the 1995 Offenbach Overtures, everyone (except the two mentioned) is dressed in red with black trim; every man wears a shako of some kind and a black mustache; every woman has red boots (costumes by Loquasto). Tipton’s lighting keeps the backdrop red.

How absurdly the men march and drill and romp with their partners! How flirtatiously the women play down their strength! The two in black search for each other periodically, finally meet, unmask, and, voilà! There are two comedic highlights. In the role designed for Lisa Viola, Khobdeh proves herself expert at a gawkiness that’s unencumbered by modesty. Unwise of her to compete with the accomplished and assured Fleet. Khobdeh’s repeated wilting pliés are a marvel; she looks as if she’s sinking into the earth but is too happily tipsy to notice.

The other hilarious passage is more prolonged. And even sillier. Trusnovec and Mahoney prepare to duel. They’re not too keen; their seconds (Kleinendorst and Graciano) fix them up and position them. The joke lies partly in the contrast between the half-hearted encounter of the dueling officers in the foreground and the squabbling and fighting of the seconds in the background. The duel turns into a competitive and extravagant display of semi-balletic feats. Meanwhile, Kleinendorst and Graciano are so busy roughing each other up that they don’t notice that the other two (shhh!) are falling in love. The four men perform this brilliantly, like seasoned vaudevillians, but with real heart.

What gusto and inventiveness Taylor’s dancers display. They are far more than virtuosic pawns for the choreographer to move around; they animate the steps without distorting them. They create characters onstage or reveal their own individuality, although they may move in immaculate unison if that’s called for. Separately and together, they are the life’s blood of his work.

If I have to miss these performances, at least I get to read your commentary.

I’m sorriest to miss the Stravinsky — I love the ending, where the “will she or won’t she” dance herself to death spins out till the last moments.