The Martha Graham Company, aged 87, is a determined survivor. It has soldiered on past the death of its sole choreographer in 1991, the sale of its 63rd Street building, and a lawsuit over its rights to Graham’s dances. Then, not long after the company took over the Merce Cunningham Dance Company’s studios in Westbeth, hurricane Sandy caused flooding in the basement storage space and damaged sets, costumes, and archival materials.

Graham might not have approved of all the company’s survival strategies—certainly not of cuts to her masterwork Deaths and Entrances for its 2011 revival, or perhaps the “streamlining” of her 1962 Phaedra for the company’s just-ended season at the Joyce (although she would probably have approved a return to the original costumes). The grouping of her works in any given season under an overall theme, such as “Myth and Transformation” for the Joyce? She might have seen that as a shrewd marketing strategy. Times change. Graham didn’t usually provide lengthy program notes, but artistic director Janet Eilber’s very charming, laid-back spoken introductions are popular with audiences the company encounters on tour.

It’s impossible to predict what Graham’s reaction would have been to the new works by others that Eilber and executive director LaRue Allen have commissioned (with an eye to what these additions to the repertory might have in common with Graham’s oeuvre). Would she have been jealous of museum-style showcases in which her works are displayed alongside lesser ones by her contemporaries? Would she have been flattered or appalled at the thought of the company building a collection of other choreographers’ variations on her 1930 solo Lamentation?

In the end, the important thing is that Graham’s work stays in the public eye, and that her masterworks be staged and performed as scrupulously and meaningfully as possible. The greatest pleasure of the Joyce season for many of us was seeing three of her greatest works—Cave of the Heart (1946), Errand into the Maze (1947), and Night Journey (1947)—presented together on one program, and Cave returning on another that ended with the 1948 Diversion of Angels— this last effectively purging away all the mythic hatred, dark urges, and desperate searching, and, in a golden high noon, hymning the transformative power of love.

Looking at these dances, you wonder how Graham came up with some of her visionary, often heart-stopping devices, and movements more gut-wrenching than anything previously seen in a dance. Cave of the Heart explores the corrosive power of jealousy through the story of Medea and her perfidious mate, Jason. You see the root of it in the opening image. The sorceress Medea stands in front of the shimmering, golden “tree” and/or garment designed by Isamu Noguchi (it also evokes both fire and the golden fleece of the legend); close behind her, kneeling or crouching, are Jason and the young princess with whom he is making an auspicious marriage; the girl, doomed by Medea’s jealousy, is sandwiched between them. Four arms reach out and around Medea as she quivers —echoing the sculpture’s branches and bringing to mind many-armed goddesses. That image then shifts into another resonant one: Jason walks along carrying the princess pressed up against him and breasting the wind like a ship’s figurehead; Medea, backing away, pulls them toward the shoals of their destiny.

The brilliant duet for Jocasta and Oedipus in Night Journey interweaves images of him as conqueror of the city and her as his plunder, of her as mother and him as son, of them as lovers. And who but Graham would think to turn the myth of Theseus entering a labyrinth to slay the Minotaur into a woman’s arduous journey into her own heart and psyche to battle an anonymous “Creature of Fear?”

I saw two casts of Cave. In both, Tadej Brdnik played Jason —a character as initially arrogant as Oedipus in Night Journey (and, like Oedipus, a role created on Graham’s much younger lover, Erick Hawkins). Stiff-legged and erect, he plants his feet on Isamu Noguchi’s little stepping stones, until Medea’s murder of his bride melts his bravado. Brdnik makes his descent into horror and despair fully believable. Xiaochuan Xie, the Princess on opening night, is charming in her innocent, flirty solo (although, as is sometimes the case, a mannerism with her mouth turns a smile into a sneer). In the same role, Iris Florentini—tilting her chin up, gazing down at the world— looks as if she interpreted the word “princess” to mean proud and self-assured and nothing more.

Natasha Diamond-Walker presents an arresting figure as the Chorus. She wears one of Graham’s most original costumes, with its wide-sleeved over-blouse in red and brown horizontal stripes. The almost tangling flurry of that and the full skirt help her to look like a tornado swirling around in her impotence to stop the tragedy. Katherine Crockett, one of the company’s three most impressive women dancers, of course, probes deeper into the role, more alarmed by what has been set in motion.

Blakely White-McGuire, who is part of that triad of splendid women, attacks the role of Medea with a fiery grimness. You wouldn’t want to meet her in a dark street. Indecision or lingering passion for Jason only make her fiercer, although I don’t mean to imply her powerful performance is without nuances. One thing that I found distracting, however, is that she often seems to be looking at the audience, rather than through or beyond us— creating the illusion that she is telling us her story even as she re-enacts it.

Miki Orihara, who during the company’s March, 2012, New York season celebrated her 25th year as a Martha Graham dancer, is the season’s other Medea. I was shaking by the end of Cave—not just because Graham’s choreography knocks you out, but because of Orihara’s performance. Her focus is almost inward; you feel what’s seething up inside her and making her body contract and quiver almost before she moves. The climatic, terrifying solo to Samuel Barber’s ferocious, juddering music comes after Medea has murdered the princess with a poisoned crown and undone Jason. In it, the dancer both devours and vomits the strip of red fabric that she draws from the bosom of her gown (Graham’s original choice of a title for the dance was Serpent Heart). When, after that animalistic fit, Orihara slowly circles her wrist to unwind the ribbon, coils it neatly onto her other palm, and tucks it back into her breast, you feel a web of emotions—relief, maybe, sorrow, resolution, acceptance of the inevitable. Unlike Euripedes, Graham ends her play equivocally; Medea is left swinging, enmeshed in the golden branches, the costume of her fury.

Orihara plays the leading role in Errand into the Maze. Only this time, the duet is called simply Errand, and it has been stripped of more than its title. The Noguchi set, with its crotch-like portal into the emotional maze, could not, apparently, be repaired in time, so choreographer Luca Veggetti, assisted by Orihara, directed an adjusted, stripped-down version. Thanks to Orihara’s profoundly sensitive performance and imaginative lighting by Beverly Emmons, the essence of the work comes across. The costumes are simple and neutral in color. The brick wall at the back of the stage is unadorned. The path into the maze is a beam of light, and a square patch on the floor indicates the entrance. The “Creature of Fear” doesn’t wear the Minotaur’s horned mask; instead his entire head is covered by a tightly fitting, flesh-colored net hood that blots out his features. Nor does he ever leave the stage, but lurks in the corners, waiting to be summoned up by the fearful thoughts inside the quaking heroine’s head.

As her imagined adversary, the formidable Ben Schultz doesn’t have the Noguchi mask to de-humanize him, so he has to work hard to avoid tilting his head or doing anything that could suggest a motive on his part. Without the set piece to barricade herself into and release herself from in the end, Orihara must show us that, in conquering her fear, she has freed herself to go on with her life. That she is able, with amazing simplicity, to manage this is a testament to her tremendous gifts. I nevertheless hope that the set, with all that it implied, will eventually be restored to the piece.

Katherine Crockett has matured wonderfully as a performer since joining the Graham company twenty years ago, and her performance as the unhappy Jocasta in Night Journey is a moving one. Her Oedipus is Schultz—appropriately muscular and demanding, although perhaps a touch too coarse with her. Some of the finest choreography in this masterly dance is for the six members of the chorus (led by Mariya Dashkina Maddux). Known as “Daughters of the Night,” they flock onto the stage like ravens—their bodies fiercely pumping, their gazes aghast, their black skirts swirling as they turn.

Humbled Jason (Tadej Brdnik) with proud Phaedra (Blakely White-McGuire in the title role). Photo: Costas

Compared with the above three masterpieces, the 1962 Phaedra falls short. It’s engrossing, though, as well as a bit lurid. The two U.S. senators who saw it abroad in 1963 hastened to complain to Congress about sending out such a shocking work on a tour sponsored by the State Department. They could have been objecting to Phaedra’s opening and closing moments. Lying on her “bed,” dreaming of her hot stepson Hippolytus, she shoots a leg into the air like a fantasized erection. Committing suicide, she stabs herself in the vagina. Hippolytus first appears behind a wall of tiny doors that can swing open to reveal a manly thigh or bulging crotch. Perhaps the senators were bothered by the lustful duet—an enactment of Phaedra’s lie to her husband Theseus about how Hippolytus raped her. She’s angry that, dedicated to the virgin goddess Artemis, the boy spurned her advances (she, however, was urged on by Aphrodite, who opens her legs explicitly to indicate where she stands.) White-McGuire and Maurizio Nardi give their duet the avid eroticism that Phaedra is denouncing to her husband, while Brdnik, as Theseus, humanizes yet another arrogant hunk.

Excerpts from a 1941 film of Graham performing Lamentation, encased in the stretch jersey tube against which she strains, precede three variations of the solo (unfortunately the film—like Peter Sparling’s montage of various Diversion of Angels casts—has been stretched to fit the back of the stage, so that the dancer appears wide and squat). An eloquent new Lamentation variation by Doug Varone joins ones by Bulareyaung Pagarlava (2009) and Yvonne Rainer (2012). In Pagarlava’s variation, to music by Gustav Mahler, Dashkina Maddux dances with, and in counterpoint to, three men, who intermittently copy Graham’s wide-legged seated position on her bench, but without the bench. Rainer has Eilber herself onstage, periodically consulting a watch, while Crockett enters trailing a skimpy piece of fabric, climbs onto a box, squats down, and shoves her limbs inside her tee shirt until she resembles a watchful, broody hen guarding her eggs. From time to time, Eilber marches across the stage and feeds papers into a very noisy shredder. (Is this about destroying your heritage? About rebirth?)

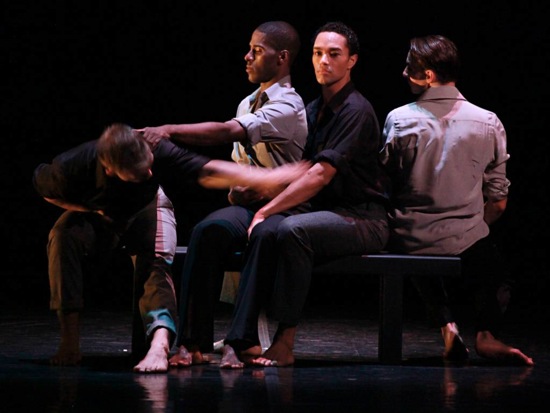

Doug Varone’s Lamentation variation. L to R: Tadej Brdnik, Lloyd Knight, Abdel Jacobsen, Maurizio Nardi. Photo: Paula Kajar

Varone has set four men (Brdnik, Abdiel Jacobsen, Lloyd Knight, and Maurizio Nardi) upon a bench longer than Graham’s and, to a section of Maurice Ravel’s Gaspard de la Nuit, builds tender images of grief and consolation. The performers lean toward, pull away from, and nestle against one another in shifting patterns that, despite their fluidity, are weighted by sorrow.

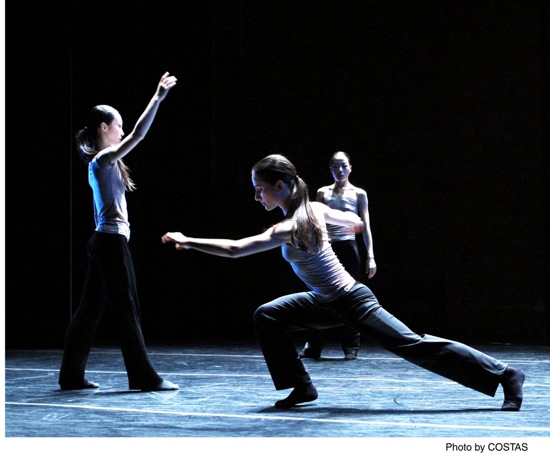

Xiaochuan Xie (L), Mariya Dashkina Maddux (foreground), and Ying Xin in Luca Veggetti’s From The Grammar of Dreams

Two dances by other choreographers grace the season. Veggetti created From The Grammar of Dreams, set to a recorded score of the same name by Kaija Saariaho. (Veggetti, the composer, and lighting designer Beverly Emmons all donated their work in the costly aftermath of Sandy.) The score is a rich one; a soprano and an alto weave or intersperse their voices through silences, their fragmented words drawn from Sylvia Plath’s poem “Paralytic” and her novel, The Bell Jar. Emmons creates pockets of light that appear, linger briefly to illuminate moments in the dance, and then go out. Five women (White-McGuire, Dashkina Maddux, Xie, Peiju Chien-Pott, and Ying Xin) often make sudden moves—sometimes in unison, sometimes all different from one another—then freeze. The sudden blackouts are like interruptions in their lives; when the lights come on again, they’re somewhere else—now two dancing in their own ways, some standing still, one sitting watching. They wear simple costumes and white socks, which means they often travel smoothly, almost skidding, but always in control. The atmosphere is one of absolute visual clarity embedded in mystery.

The other work new to the company is Richard Move’s The Show (Achilles Heels). The piece was commissioned in 2002 for Mikhail Baryshnikov’s White Oak Dance Project and starred Baryshnikov. Remounting the piece for the Graham company seems both appropriate and audacious. Move, of course, is the great Graham impersonator and scholar, whose scrupulously designed, high-caliber variety shows (beginning in 1995 as Martha@Mother) both satirized and honored Graham. Numerous New York theatergoers might never have become interested in her without him.

The Show is also appropriate in that it fits nicely into the “Myth and Transformation” theme. The hero, Achilles, inhabits Graham’s favorite mythic territory, as does his moral dilemma. In The Iliad, when the Greek army badly needed his skills, he stayed in his tent, nursing his rage over an insult his commander, Agamemnon, had meted out. His lover, Patroclus, donned Achilles’s armor, went in his stead, and was slain. The hero’s grief and shame finally roused him to fight.

Quiz-show hostess Athena (Blakely White-McGuire) and contestant Achilles (Lloyd Mayor). Photo: Paula Court

What’s audacious about The Show (Achilles Heels) in terms of the Graham repertory is Move’s delight in gender-bending, fashion, and camp. Achilles’s vulnerable heel becomes plural—a pair of golden stilettos that he chooses over the blood-red pair Patroclus offers him. Stalking proudly in these, he evokes both runway models and the tragic actors of ancient Greece, who made themselves taller than life with platform shoes.

To inform us about the plot, Move’s hero (Lloyd Mayor) answers questions to do with the Trojan War (correctly, of course), posed by an exuberant quiz-show hostess (Mayor and White-McGuire, channeling Athena, lip-synch Baryshnikov and Deborah Harry of Blondie, who appeared live in a 2006 revival of Move’s piece at the Kitchen). This Achilles knows the work of Constantine Cavafy, and his uncollected winnings are in euros. The score by Arto Lindsay is augmented by Harry’s voice singing Blondie gems, such as “Beautiful Creature,” “War Child,” and “No Exit,” that create their own strange alliances with the plot.

Like most Graham’s heroes, this one (Lloyd Mayor as Richard Move’s Achilles) marches forth. And dies. Photo: Paula Court

Amid the muscular goings-on of a trio of men and a softer trio of women, Helen of Troy (Crockett) parades her beauty and her quandary in homage-to-Graham steps. Diamond-Walker, bare-breasted, appears briefly as Achilles’s loving horse, Xanthus. The Show does have some dead-air moments and judicious editing wouldn’t be amiss, but there are many pungently theatrical moments, as well as poignant ones. After Patroclus (Jacobsen) has toweled off Achilles, he rubs his own face against the towel, and the two, cheek-to-cheek, hold up a golden mirror to share a reflection the way modern lovers pose for a cell-phone memory. A white paper bird flaps its wings on the dead Patroclus’s chest (the performer invisibly manipulates it), as if his spirit were calling out to the grieving Achilles, who dance around the corpse, then lies on top of Patroclus and transfers the bird to his own breast to join them both. The show however, must go on, and heroes never really die. Mayor, a handsome, boyish newcomer to the company, moves into a center spotlight, and glittering confetti rains down on him.

Glitter brings me to a quibble. I can tolerate (barely) the sequins that, at some point were added to Medea’s costume in Cave of the Heart (Graham in her later years had exceedingly poor eyesight). The gleaming particles in the “snake” are less bearable. And the glitter that Diamond-Walker appeared to have stuck to her eyelashes for Diversion of Angels? Definitely out of place.

If you’ve seen a lot of Graham works many times, you develop a jealous eye. I’m open to performer’s varying interpretations, although bothered by, say, a leg extension so high that it detracts from the important message sent out by the dancer’s contracting torso, and by additions to, or subtractions from, crucial passages in the choreography. In the gorgeous Diversion of Angels (Graham’s paean to her dancers), there’s a strange, enigmatic moment when the woman of the Couple in White (seen as the most serene of the three leading pairs) steps—almost unseeingly—onto the thighs of her partner who is lying face down; he bends his knees, and, for a few seconds, she sits enthroned on the upraised soles of his feet. Diamond-Walker simply placed her feet beside Jacobsen and then bent her knees to appear to sit on air. In a charitable mood, I might wonder if Jacobsen had a injured leg to which Diamond-Walker was accommodating, or whether she was covering a misstep, but if what she did (or didn’t do) represents an option, I’m distressed.

At the very end of Diversion, the passionate woman of the Couple in Red streaks across the stage on a diagonal, giving a physical presence to the exultant cries in Norman Dello Joio’s score before her trajectory takes her into the wings. Her passage is just a fleet, wide-striding run, her arms and upper body swinging from side to side. It’s like seeing a cardinal flash past your bird feeder. At the Joyce, White-McGuire broke the pattern by inserting a couple of moderately-scaled leaps. Was this a delaying tactic because the stage is relatively small? Whatever the reason, the change isn’t a minor matter akin to that of a ballet star doing an extra pirouette in Le Corsaire; that run, as Graham conceived it, makes a powerful emotional and musical climax seconds before the lights go out.

I’ll now cycle back to sentence that I wrote at the beginning of this long review: “In the end, the important thing is that Graham’s choreography stays in the public eye, and that her masterworks be staged and performed as scrupulously and meaningfully as possible.” I’m grateful that during the company’s 2013 New York season, the directors, guest choreographers, collaborators, and dancers, by and large, succeeded in that mission.

My oh my Ms. Jowitt, how you do go on, and please, please continue to do so. I do take issue with you (and many others) about the real subject of Cave of the Heart–I think it is not about jealousy, although that’s part of it, but about betrayal, a terrible betrayal. I came to that conclusion while watching I forget who perform the role of Medea here in Portland, at a time when I was myself feeling acutely betrayed, though fortunately not murderously so.

Thank you, for the umpteenth time, for putting me into the theater with you.

I think the simple answer is that Graham was inherently theatrical in her thinking, and that made her a great dramatist, which made her dances great. Her peers also understood the importance of the dramatic context, as well as the importance of music and scenic as well as costume art. You may well attribute that to the influence or example of Diaghilev. The lack of these elements is why dance has suffered such a devolution since the founding generation, with few exceptions. Even Paul Taylor slips in that the footwear of the dancers is not parcel of the costuming, ie. always the same casual flat jazz shoes or barefoot, as I recall.

Jazz choreographers inherited the mantle of theatrical greatness far more than post-moderns, who are stuck in the artistic egocentricity of conceptualism, etc. But, they too have lost their integrity, with the abandonment of core movement vocabulary, be it ethnic, modern or urban street dance/folk dance.

Would that funding were not always the issue in providing a balanced approach. But some choreographers, with as little as one dancer, will still achieve synthesis.