I regret not having been able to see Carte Blanche, the Norwegian National Dance Company, perform Corps de Walk at the Joyce Theater. In this piece by Sharon Eyal and Gai Behar, the dancers, I read, have whitened hair and wear blue contact lenses. What better illustration of the Nordic mini-festival’s name: Ice Hot?

The other participants were the Tero Saarinen Company and Danish Dance Theatre. If Saarinen’s Scheme of Things tells us something about his Finnish homeland, that may because of his fascination with light, which in far North countries is an all-or-nothing affair for much of the year. His 2002 solo Hunt, programmed with Scheme of Things at the Joyce, and his miraculous Borrowed Light ( seen at Jacob’s Pillow in 2006 and 2012 and at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in 2007) are both, in some sense, dialogues between light and darkness. The superb lighting designer Mikki Kunttu creates the landscapes that express those opposites, whether interior or exterior.

Jarkko Lehmus (foreground), Pekka Louhio, and Mikko Lampinen in Scheme of Things. Photo: Sakari Viiko

In Scheme of Things (created for Nederlands Dans Teater 1 in 2009, and transferred to Saarinen’s company two years later), the stage is a place of shadows and glare, of beams piercing darkness. Rows of amber lights intermittently blaze on a tall narrow wall, behind which the six dancers disappear from time to time. These people seem to be caught in a trap of their own making—perhaps just the snares of modern living. At the beginning of the piece, they’re upstage with their backs to us, jerking themselves about in various ways or racing here and there. They wear everyday clothes by Erika Turunen, unless you count the severe, long-sleeved black gown worn by tall Annika Hyvärinen. The music collage (featuring Biosphere, Jeff Buckley, Trey Gunn, Higher Intelligence Agency, and Jarmo Saari) does little to calm them down, although they occasionally freeze in their tracks, as if the temperature has plummeted or their inner circuit boards have shorted out.

Two standing follow spots in the near corners of the stage (manned by clearly visible crew members) lure these people. As a group, they sneak up on one of the lamps and snatch at the moving beam as it slants to the floor. They cluster around Jarkko Lehmus and pluck at the air around him, as if they’re catching stuff that emanates from him (a sound like that of a train clatters by). When Maria Nurmela approaches the other light and stands staring into the distance, the others watch her closely.

But no one is truly at ease for long. The dancers thrash and slash about. They caress their own bodies with slippery unease. A crash of sound sends them toppling to the floor. Hyvärinen and the much smaller Natasha Lomi wrangle. Mikko Lampinen dances as if possessed. Lehmus staggers and twitches; you can imagine a storm of tiny insects stinging him. Strange events ensue. Hyvärinen yanks a shirt off Lampinen; he’s wearing an identical one underneath it. She pulls that off too. And another. Her own long gown is made of some immensely stretchy material. The others (including Pekka Louhio) surround her and start pulling at the fabric, their shadows looming on the back wall. A sleeve stretches a yard beyond her hand; eventually she’s caged within her own garment.

As the dance progresses, the amber lights on the rear panel go out intermittently, come on again, decrease in numbers. What message are they sending? Scheme of Things is fascinating, troubling, enigmatic. The characters that the splendid performers embody move violently but without apparent malice. They understand order and community but seethe within it.

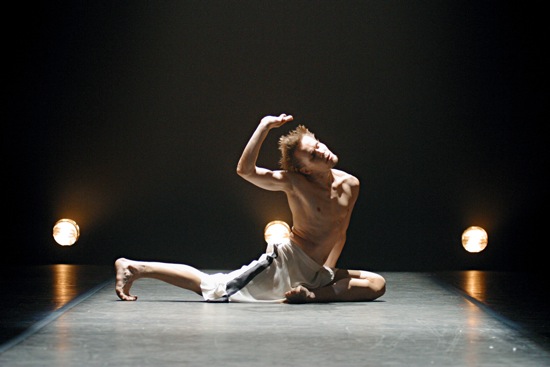

I’ve seen Saarinen perform his Hunt several times, and I can understand why he says he may soon stop dancing the piece that he choreographed over a dozen years ago. He faces the score of Igor Stravinsky’s formidable Sacre du Printemps alone—as both the hunted and the hunter. The weapons may be memories and the depredations of time. Or anything we struggle against or hide from.

He begins moving slowly and deliberately in Kunttu’s hazy light. He’s bare-chested above a filmy white skirt. When the music’s deep pulsing begins, he bends to touch the floor, to smooth it (erasing his tracks? following another’s?). A semi-circle of lamps placed on the floor adds to the impression that the stage is a liminal arena, a place where transformations happen. Saarinen arches his body, opening himself to a ray from above; he bathes in a pool of light.

The music is his territory too. He doesn’t dance to it in the narrowest sense of that term, but it marks his path and informs his decisions. He’s still moving smoothly, close to the ground, when the music emits a huge crash, but shortly thereafter, he’s jumping forward on his knees. The solo is an ordeal, but not a mindless one. Saarinen runs and leaps, turns and falls, but you see him thinking, wondering.

The only living being onstage, he becomes a canvas for a flood of images. The object resembling a cloud that slowly descends above him is a full, white skirt of many panels (designed by Erika Turunen) Once he has fastened it about him, Maria Liulia’s images are projected onto it and onto his face and body.

When he stands facing us, moving his arms, the montages flash on and off in time to the second part of Stravinsky’s relentlessly building music. They crawl up and down his body, depending on how he moves. Multiple pinwheels feather him; they seem to contain his tiny image, seen from above, at their coiled centers. As the music for the sacrificial dance pushes toward its violent end, he rushes, collapses, rushes on. The flashes of a strobe light capture him in the air.

The lights, the music, the projections have bombarded him; he’s exhausted, but he’s flying. That’s a dancer for you.

The Danish Dance Theatre doesn’t proclaim its Danishness. Tim Rushton, who has directed it since 2001, is British. The current members of the excellent troupe he has built hail from Greece, Italy, Sweden, Portugal, the United States, Brazil, and Russia; only one, Maxim-Jo Beck McGosh, was born and raised in Denmark. But as dancers, they have, inevitably, become a community, and, in Love Songs, Rushton wants us to know that. Privacy isn’t an issue. Whoever’s not dancing may sit on one of the chairs in a row at the back of the stage—lounging, chatting, taking in the scene. Another option is standing around, watching one another with interest. While Fabio Liberti is showing off his mobile hips, Beck McGosh strolls around him, inspecting him.

The dancers’ casual behavior and informal, variegated attire (by Charlotte Østergaard) contrast to Thomas Bek and Jacob Bjerregaard’s lighting, which is sometimes gaudy (four overhead lamps spill purple light at one point early on). Classic songs (such as “My Funny Valentine,” “Come Rain or Come Shine,” “All of Me” ) suit the rehearsal room, the iPod, and the nightclub equally well, and the Danish jazz singer Caroline Henderson (in recordings) delivers them marvelously.

There’s also a contrast between the informal behavior and the more formal passages. Rushton is good at getting his cast of twelve into, say, three lines, facing front, doing big, earthy, strenuous, things in counterpoint or unison. But for me, the best parts of Love Songs are those in which he shows us the individuality of the performers. I like watching Luca Marazia, jitter along—a small cheery fellow, very pleased with himself, but mostly alone. There’s an appealing scene in which Alessandro Sousa Pereira and Emily Nikolaou dance lavishly together, until he brings her a chair to sit on, and— after a bit more togetherness—grins and goes. Björn Nilsson walks in and gives Nikolaou a big smacking kiss on the cheek; she slaps him. Oof! Ana Sendas orders him to sit and watch while she and Stefanos Bizas comply with a recorded voice that’s giving advice on the dos and don’ts of courtship. This sets off a scene in which two people–many pairs of them— rush toward each other from opposite sides of the stage, kiss or hug, and race away again.

Love Songs. Ani Amit (foreground), Nassim Beki (former company members), and Erik Nyberg. Photo Björn Orsted

Rushton is so good at encounters that it’s disappointing when his finely designed and rhythmically smart group passages of dancing don’t tell you much about the people you’re beginning to love. And midway through the piece, after the performers have gone back to the chairs and, in dim light, changed into slightly dressier outfits, he begins to insert a few familiar virtuosic lifts into duets. Is he being ironic? Or because now the workday is done and these people are ready to party, can happiness justify propelling women into the air? When Bizas hoists Sendas high—even into one of those Russian-style lifts in which the man straight-arms the woman up to lie decoratively on her side over his head—it’s a shock.

That’s because many of the duets that occur in both parts of Love Songs are so interesting choreographically and so believably sensuous. The encounter between Milou Nuyens and Erik Nyberg is one of those that make you feel the heat of body against body as the intimacy grows between them. However, even though Rushton veers momentarily into a cliché, he directs his terrific dancers astutely. They perform every step as if they understood its possible nuances, as if kicking a leg up or feeling the pressure of another’s hand expresses something important about this day in their lives.

I like the valuable info you provide in your articles. I’ll bookmark your weblog and check again here frequently. I’m quite sure I’ll learn lots of new stuff right here! Best of luck for the next!