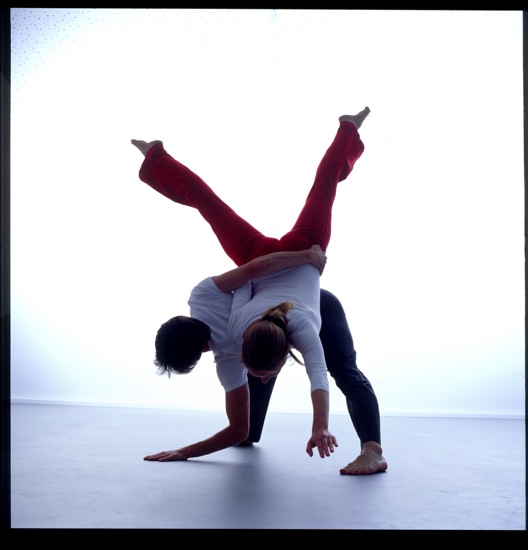

L to R: Silas Riener, Cori Kresge, Rashaun Mitchell, and Melissa Toogood in Mitchell’s Interface. Photo: Stephanie Berger

I remember years ago attending a evening of solos by an Indian dancer; it could have been Balasaraswati or Ritha Devi, and shortly after that, going to a performance by (maybe) American Ballet Theatre’s Bayadère. My friend and colleague, Marcia B. Siegel also saw both performances. When we spoke later, we both remembered how the familiar classical arm and hand movements of ballet had suddenly seemed so simple and the faces of the dancers so expressionless, compared to the precise complexity of the Indian performer’s fingers and hands, and the multitude of emotions that appeared on her face.

We got over it, of course. But I still occasionally think about the role of the face in western theatrical dance, especially in works that purport to tell no stories (I’m not counting the numbers by show-biz chorus dancers whose smiles sparkle on demand). Two back-to-back performances I attended this past weekend raised the issue of the face in very different ways.

Friday, March 15, Rashaun Mitchell’s new Interface at the Barshnikov Center. His facial expressions and those of his splendid collaborating dancers—Silas Riener, Melissa Toogood, and Cori Kresge—are vital to the concept driving the piece. Mitchell, a relative newcomer to choreography, danced in Merce Cunningham’s company for its last eight years of life. Riener and Toogood are also company alumni, and Kresge was a member of Cunningham’s Repertory Understudy Group, as well as a teacher in his school. Mitchell is in the process of coming to terms with and breaking away from his heritage, so while the dancers sometimes move with serene, elongated bodies and stretched, articulate legs, they also crouch and crawl, shudder, jiggle, and contort themselves in ways that set one part of the body against another.

In addition, for no apparent reason, they will smile or look anxiously in one direction with a furrowed brow or squeeze their features together as if they’ve smelled something disgusting. Part of the rehearsal process for Interface involved the performers looking into mirrors to investigate what could be done with their faces. An interesting thing happens in the performance. Although the facial expressions rarely coordinate with what the rest of the body is doing and aren’t meant to enhance its actions, a grin, say, or a grimace gives the performer unavoidable feedback, which then subtly alters the movements of the rest of the body. Try this for yourself: screw your nose up toward your eyes, lower your brows, open your mouth wide, and snarl or hiss. Don’t you feel a further impulse to hunch your shoulders? Don’t you feel, for a fraction of a second, enraged?

Facial expressions—especially extreme examples of them—have been taboo in most post-sixties contemporary dance and in the work of masters like Cunningham. The thinking is that the body will do all the expressing that’s needed (although most of us appreciate a dancer whose face looks alert to life and what’s going on around him or her). Mitchell has carefully choreographed the expressions in Interface with a postmodernist’s appetite for disjunction, and he uses them sparingly but fervently. Hot material employed coolly.

The setting and music add to the impression of things taken apart and reassembled. The visual design (by Fraser Taylor, Davison Scandrett, and Mitchell) consists a white floor in the middle of the larger black one and tall screens that cover some of the Howard Gilman Space’s two windowed walls and/or the areas between them. The screens are composed of large patches of black-and-white designs (maybe on fabric). Some show reedy vertical lines, some a ragged weave, others scribbles; they’re diverse enough in the black-white ratios and the patterns for you to notice that all designs are repeated two or three times. A few areas can also hold small videos. The original music that Thomas Arsenault (Mas Ysa) creates and plays at a console (I didn’t get a close look at his equipment) is highly variegated in timbre and texture. It may sound like a faint scratching, wind, growls, balls rolling over a floor, footsteps, men talking, and more—all rising and sinking in an abrasive storm of sound that occasionally calms down, even falls silent.

Scandrett’s lighting and Mary Jo Mecca’s understated, individualized costumes also have an impact on the arrestingly enigmatic dance. The lighting, for instance, can make the windows reflect the dancers. You know what you see; but pondering all that it can mean, means not to mean, and does mean keeps you watchful. Could this dance bite?

The four dancers begin at the corners of the white square, and at first you’re not sure they’re moving at all, so slowly and subtly do they begin to lean and crank their bodies; they look almost doll-like in their attention to joints. It’s only after they’ve reached the center of the room and stand looking around that you notice the changes in their faces: a tongues pushing out a cheek, a mouth pushed poutily forward, lips parting. At one point, as the four back up to the corners, they keep their eyes on the person opposite, but avert their faces slightly, as if fearful and retreating.

Riener on Mitchell, Toogood and Kresge at back; Mitchell onscreen keeps watch. Photo: Stephanie Berger

Curious moments stay with me. Mitchell striding around the black border with Riener, bent over, his cheek glued to Mitchell’s hip, struggling to keep the pace. Riener balancing on the ball of one foot for a very long time. Mitchell fallen face down on the floor and Riener standing on his back for an even longer time. Toogood releasing her hair while the others watch. Her hair becomes a part of her solo—a mask, as well as something she can lash around or use to sweep her feet with once she sits down. Her face is neither expressive nor inexpressive; it’s invisible. Without animosity, Mitchell grabs her ankles and spins her until you hurt for her, then slings her away. She lies still until Kresge sits her up and carefully braids her hair. Toogood looks almost as if she might cry. Is this arbitrary choreography or expression fomented in the moment?

Interface is a weave of everyday movements (like walking over to look out a window), ones that challenge the body in dancerly ways, and ones that put it in jeopardy. The facial expressions, pruned away from movement that might corroborate them, remind us of how often we suppress or modify what our faces could reveal.

Interestingly, one of the first dances that Merce Cunningham made by chance procedures, Sixteen Dances for Soloist and Company of Three (1951) based its sections on the nine permanent emotions of Indian dance—mostly in abstract ways, but his interpretation of hatred (or, the odious) was a warrior yelling at his foe. In one photo, Cunningham’s mouth is wide open.

Saturday, March 16. In John Scott’s The White Piece at La MaMa’s Ellen Stewart, its fourteen dancers always look engaged, but at times the individual contributions that they make or copy, suggest extreme situations. Then their faces reflect what their bodies and words are telling us—showing elation, lasciviousness, desire, fear, disgust, anger, pride, and more.

In 2011, when Scott brought his Fall and Recover from Ireland—where his company is based— to La MaMa, ten of the twelve performers were people whom he had met through the Centre for the Care of Survivors of Torture (CCST), where he first taught a workshop in 2003. They had come to Ireland for asylum and were able to become citizens. We didn’t see in the dance the violence that had caused them to flee. The theme of Fall and Recover was survival against all odds and the power of community to heal.

The White Piece explores related issues: The struggle to achieve identity in a new land, the threat of deportation, the Kafkaesque bureaucracy that manages immigration, the courts, the language problems. Its title refers to the belief among some Cubans and the Yoruba people of Africa that a piece of white cloth has the power to heal and purify. For beleaguered asylum seekers that Scott has known (some of whom perform in The White Piece), dance is that healing magic. In The White Piece, Scott has created a potent piece of theater. If it’s not moving in the same way that Fall and Recover was, it’s because the two main topics, love of others and a sense of self, are shown through game structures that can be entertaining as well as thought-provoking. If you hadn’t read the program note, you might not fully sense its dark underpinnings.

The performers begin by walking around the Ellen Stewart Theater, where the seating has been arranged along one of the rectangular space’s long sides. They vary in age, girth, color, country of origin; some are professional dancers, some are not. They hold sheets of white paper, from which, one at a time—maybe in random order, maybe not—each reads a sentence about the forms love may take. Some are universal: “Love as an agent in transformation.” Some summon up specific images: “Love as a fan in a stuffy room.” Some are quirky: “Love as a happy tractor” or “Love as a horny seagull.” The reader then expresses that thought briefly in movements that the others copy as best they can; sometimes vocal noises are involved. Theme and variations become an instant world of similarities and difference.

A number of these shared recipes are simple and visually pleasing, e.g. everyone slowly spinning, arms spread wide. Others are violently energetic, and it’s permissible for some performers to abstain occasionally. All are okay for rolling on the floor or making suggestive hip motions, if that’s what’s called for, but not necessarily for yanking and hurling themselves around when Philip Connaughton defines love as “a battle with yourself.”

Some of the images in The White Piece suggest people lining up to pass through customs or treading a border warily or finding refuge in enigmatic ways. At one point, Connaughton lies on his back, and Cheryl Therrien (a former Merce Cunningham dancer) lies face down on top of him; both turn their heads to stare toward us. Ashley Chen bends over, hinging his body at the hips, and Connaughton lies atop that human peak and swims in space.When the performers all line up facing us, trying to follow James Hosty’s directions, a cacophony of gibberish emerges.

Everyone is involved in some way almost all the time. While Hosty, Chen, and Daniel Squire (the latter two also former members of Cunningham’s company) call out and demonstrate the various likes and dislikes and habits that define them, Scott provides momentary counterpoint by leading a parade of other cast members along the back of the space. Then Therrien follows Joanna Banks along another path. The three men are tirelessly inventive. In a metaphor for community, if one of them calls out “Me: cherry pie” as Squire does, and follows it with an energetic danced equivalent of what that means to him, then the other two have to acknowledge— by repeating his words and movement— that these matter to them as well, however alien they feel. By the end, all the dancers are wearing white clothes, standing in a line that leads away from us, and moving in a determined community of “me”s.

Throughout the piece, Ivan Birdwhistle’s score provides an unobtrusive medley of evocative sounds, and Eric Würtz’s lighting warms and cools the space subtly. Philip Sandstrom realized the lighting at La MaMa, because, in an ironic coincidence, Würtz could not come with the company because of visa problems. I puzzled afterward about the orderly montage of photos behind the dancers, with various images of radical artists and political activists and articles about them repeated ever few feet. These had been used during rehearsals to inspire the performers and were there during the show to remind them of their power to speak out.

In retrospect, I appreciate the quiet moments in The White Piece—say, Banks kneeling at the head of Mutufau (Junior) Kehinde Yusuf, who’s lying supine, and gently patting him and gesturing as if casting a healing spell. And the stillnesses: Rebecca Reilly just standing with her arms held out. Also the wilder ones: Hosty stamping out a dance while swinging his arms and emitting shrieks and calls, like a furiously protective mother bird. All the individuals are interesting to watch and listen to; that includes Crinela with her calm demeanor and faint Eastern European accent; Kiribu of the powerful singing voice; slim, contained, unexpectedly strong Sarah Patience; Florence Welalo Poudima of the intent gaze.

This brings me back to facial expressions. They’re an intrinsic part of everything in The White Piece that involves speech or particularly explosive or straining movements. Yet sometimes the performers’ faces are expressive in a more transparent way. At one moment, Welalo Poudima catches my eye. Her beautiful face is still, but she’s seeing an imagined something—seeing it with her whole being.

bella lewitzsky once said in class

that the face is also a muscle.

this set the wheels turning in my thoughts……

so often once goes to performances today and see beautifully trained dancers,

but they seem in large amount faceless.

i think this is a fault of much of the teaching today, where it is often said everything is in the body.\

one forgets that the face is also part of that body

I think the face has a lot to do with how the audience interacts with a piece – great thoughts here Deborah.