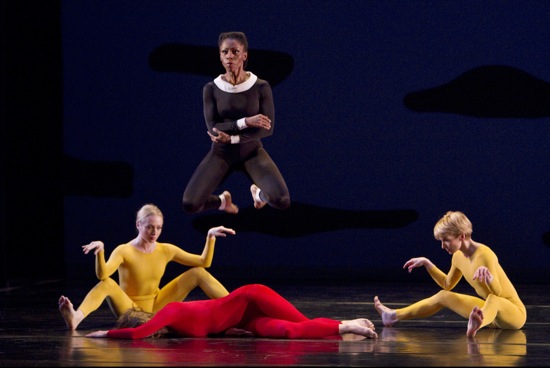

Paul Taylor’s Scudorama. Laura Halzak (prone), Michelle Fleet (in air), Jamie Rae Walker (L), Julie Tice (in an earlier cast). Photo: Paul B. Goode

Wishing Happy 50th birthday to a dance like Paul Taylor’s Scudorama mightn’t be a good idea. The cake could blow up in your face. You have to be a bit crazy to love this dance. Made the year after Aureole, which lives on in an indestructible springtime, Scudorama cringes and crawls and hides from view. The current revival dates from 2009.

Scudorama’s 1963 premiere at the American Dance Festival in New London, Connecticut, was, by all accounts, disastrous. The score by Clarence Jackson didn’t arrive in time. Neither did the set by Alex Katz: three hanging rows of dark plywood clouds. The eight dancers, including Taylor, performed in silence. Make that seven-and-a-half. Dan Wagoner had torn a muscle in his calf and could manage only the crawling and limping parts. The purgatory that Taylor had intended to suggest became rather too real.

The presence of this weird, grim, at times comical early work on the Paul Taylor Company’s Lincoln Center season may not be coincidental. Scudorama has shadowy links to the big-news birthday kid of 2013, the ballet created one hundred years ago by Igor Stravinsky and Vaslav Nijinsky. Because Jackson’s music was extremely slow in coming, writes Taylor in his devilishly readable memoir, Private Domain, the music that the dancers worked to throughout rehearsals was Le Sacre du Printemps.

The program particulars are prefaced by a quote from Canto III of Dante’s Inferno. Virgil, his guide, tells him that the denizens of this purgatory “are the nearly soulless/ Whose lives concluded neither praise nor blame.” They relive degradation and flabby morality. That’s about it. There’s a moment in which Laura Halzack has fallen after a long solo bout of dancing and lies crumpled on the floor; Jamie Rae Walker and Aileen Roehl, two small blondes in bright yellow leotards and tights, sit beside her like two damaged angels, legs apart, hands drooping. They remind me of women who can’t do serious work until their nail polish dries. They’re commiserating with her in their own way. Or perhaps they’re guarding her, because three prim women in black with little white collars (Michelle Fleet, Parisa Khobdeh, and Heather McGinley) come to stand over Halzack and make fierce, jabbing gestures down at her.

The dancers spend a lot of time slithering along on their bellies—entering, exiting, going nowhere. What’s interesting is that they seem hapless, not fully aware that they’re doomed. When Sean Mahoney arrives in a jacket and trousers he’s surrounded by a litter of bodies and a mysterious heap of something covered with brightly patterned fabric (beach towels cum shrouds). The people begin to stir and scrabble along; one grabs at his ankle. One of the two under the shroud drags the other away on it. He shows no fear. Before long, he has shed his coat and begun to crawl too.

This is not a happy place. At the beginning of Jackson’s score, you hear what could be insects (like those that torment Dante’s morally destitute souls), later there are bird-like sounds. Light piano notes give way to drunken carnival music. Sometimes the “sky” turns lavender (Jennifer Tipton recreated Tom Skelton’s original design), sometimes yellow. At one point, Michael Trusnovec (or was it Mahoney?) enters with Walker, crouched over, squatting on his right shoulder with one leg; she has the other wrapped around his neck. He seems to be wearing a padded yellow mask.

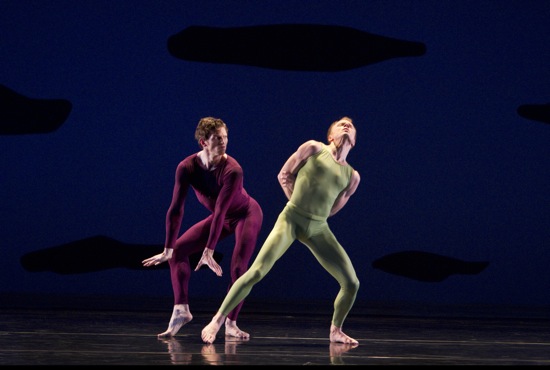

Trusnovec is another recent arrival, but soon he too has stripped to leotard and tights and is getting around like an alligator. Amid the collapsing, the lying in heaps like bodies in the gas chambers of Auschwitz, the lashing and swatting the bright towels around, the dancers exhibit both simian behavior and courtly manners. They’re precise in their distortions except when they panic, as Trusnovec briefly does. When the three women in black hold their hands, limp-wristed, in front of them, they could be secretaries remembering their typewriter keys or poodles trained to walk on two legs. These women are almost always in unison— prancing or walking with springy steps or whipping off quick, tricky footwork; sometimes there’s a trace of minstrel-show strutting in their steps (and in the music).

Mahoney and Trusnovec also hold up paws when they confront each other, before whipping themselves into tantrums of desperation. Mahoney yanks Halzack up from where she lies and pulls her through a disheartening duet—bowing to her, slinging her around, jumping over her. They all dance as if their limbs were being torn out of their sockets of their own volition. Mahoney is especially fine in roles that Taylor made for himself early on (the one in Junction as well as in Scudorama); he understands possession.

Those of us who saw Scudorama when it was new wondered what the hell it was and whether this brilliant, disturbing, unpredictable choreographer would destroy himself. We needn’t have worried, of course, but, confronting the dance again, I understand our fears.

Twyla Tharp made her debut in Taylor’s company dancing in Scudorama. I wonder if she ever has nightmares about it.

Deborah, I’m glad to read that you also, and still, find Scudorama mysterious and puzzling. This was my first viewing, and I found it fascinating, but totally undecipherable.

I’ve always admired your mind, and your generosity and empathy and insight into dances that sometimes left me clueless — but I think this wonderful piece outdoes anything else I recall for verve and gusto and energy in writing. What did you have to say about “Phlegmatic”? cuz you’re GREAT on this subject….

I’m taken aback (read: thrilled) by your generous words. “Phlegmatic” huh? I’ll have to cast my mind back to what may be my favorite part of Balanchine’s 1946 “Four Temperaments.” A few years before Todd Bolender died in 2006 at 92, I had the great, if frustrating, pleasure of attending one of the Guggenheim’s Works & Process events and watching him coach Arch Higgins of the New York City Ballet in the role that was made on Bolender. This was frustrating because Bolender was so consummately loose and yet precise in an understatedly jazzy fashion, and Higgins seemed to think that Bolender was performing the steps the way he did because he was old, and therefore he (Higgins) shouldn’t try to copy him closely.

I received the following from Marcia B. Siegel via e-mail and post it with her permission.

Just read your review of Scudorama. Many things I don’t remember—but I didn’t see the 2009 revival, maybe it just got changed.

What I do remember is: I have no sense of a “disastrous premiere.” It was ugly and intimidating, but it didn’t seem scandalous to me. I thought the piece incomprehensible, but I liked it. My sense is there was no program note at first—you were left to infer hell and damnation yourself, or whatever else came to mind.

True, Jack Jackson didn’t finish the score in time—supposedly they rehearsed it to the Rite of Spring—but by the premiere they at least must have had a piano reduction by Jack, I certainly don’t remember them performing in silence. Angela Kane’s chronology quotes Allen Hughes talking about the score in the NY Times, 19 August of ’63, which was probably the Sunday after the premiere.

I don’t remember that Dan could only crawl, I have a pretty clear image of Twyla sitting on his shoulders as he stomped around, maybe in place. But maybe that’s something I conjured up when I was writing about her, or maybe it’s from some rehearsal photo. Dan would remember ALL of this. By the way, Kane says Dan didn’t perform at all in the premiere! Maybe what I’m visualizing was the second performance. If there was one.

I do remember the lashing about of the big beach towels. And Paul, in a grey suit that he probably took off, with leotard underneath. The women began in short trench coats, I think. The combination of street clothes and dance clothes was disturbing at the time. Not to mention the towels.

Also, both the contemporary pictures and your description seem to be of a much less menacing dance—could be Paul smoothed it out, or the dancers can’t now achieve the denseness and grotesqueness there was in the beginning. I do remember thinking, in 1963, how can they be doing these bizarre things and having no expression on their faces? I wonder, now, how much of it came right out of Junction.

I used the word “disastrous” in relation to Scudorama’s premiere to indicate all the things that went wrong for the company, not to imply that the audience perceived the dance as scandalous, or received it badly.

Dan Wagoner, according to Taylor, did not dance in Aureole or Piece Period (his solo was cut in the latter), but he did do what he could in Scudorama.

About the music. I ran into former Taylor dancer Senta Driver today in front of the neighborhood supermarket. She remembers the premiere being danced in silence and wonders if perhaps there was more than one performance, by which time another score was obtained. (Taylor writes in his book Private Domain that the score that was fintended to arrive before the premiere was discovered ten years later in the New London post office.)

Scudorama is plenty menacing still.

Correction to my earlier post:

Marcia Siegel reminded me that the lost score for Scudorama was, according to Taylor found in the New London bus station years later, not at the post office. Siegel, incidentally, was backstage at the premiere, having volunteered for crew duty.