On Thursday, January 31, the second day of the Trisha Brown Dance Company’s season at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, it was announced that Brown, because of health problems, had retired as artistic director of the company she founded over forty years ago, and would choreograph no more dances. Consider these words bordered in black—mourning for the works she might have continued to give us.

Although many in the BAM audience that night had been expecting just such an announcement, most did not yet know of it. The occasion was festive. The superb performers were cheered over and over. A revival of the 1983 Set and Reset was being presented this night only, and members of the original cast and others who had performed the marvelous dance were invited to rise from their seats and be applauded. Brown is seventy-seven now, and quite a number of the spectators who filled the house to overflowing had followed her career since her rambunctious days in the 1960s as a founding member of Judson Dance Theater.

Over the decades, her intellect, her delight in movement, her wit, her originality, her novel structures, her appetite for exploration have challenged and thrilled us. The BAM programs reveal not only what is consistent about her style, but also how differently she approached each new project.

All but one of the programs opened with Les Yeux et l’âme, a work she created in 2010 as part of a production of Jean-Philippe Rameau’s opera, Pygmalion. At festivals in Europe, her company performed it with Les Arts Florissants, conducted by William Christie. I didn’t see Les Yeux et l’âme at BAM, but at Jacob’s Pillow in the summer of 2011 (performed, as at BAM, to the recording by Les Arts Florissants). As in all the dances that Brown—beginning in the mid-1990s—composed to music of the past, her choreography doesn’t cling to the beat or swoon along the melodic line; it captures something about the musical structure and ambiance. Collaborating, so to speak, with Rameau (1683-1764), she created with her dancers the allées and vine-wrapped trellises and formal gardens that Rameau’s baroque traceries invoke. Brown’s own slim, black, line drawings dart and whorl and dart again across the backdrop.

Set and Reset is one of a series of 1980s works that she dubbed “unstable molecular structures.” Forget formal gardens; a comparable metaphor might be birds fluttering and flocking in an urban landscape. There’s always something moving onstage—not just the seven dancers. Their filmy costumes, silk-screened with black-and-white photos by the piece’s designer, Robert Rauschenberg, stir in the wind of the performers’ motion. So do the translucent curtains that edge the space and make the border between onstage and offstage porous. Black-and-white film montages flicker on Rauschenberg’s set—two pyramids flanking a four-sided shape. The three structures, standing onstage as Laurie Anderson’s music begins, gradually rise to hang above the dancers.

Anderson’s splendid score is also full of changes, despite its ongoing, ringing pulse. Woodblocks, or a sudden screeching, may sound out above deep bass tones. Anderson’s voice—after its first introduction into the texture with a chanted, repeated, and varied “long time no see”— interjects varied enigmatic syllables and tones, as if she were dissecting a phone conversation—dial tones, ringers, and all. The lighting that Beverly Emmons designed with Rauschenberg is beautifully subtle and clear.

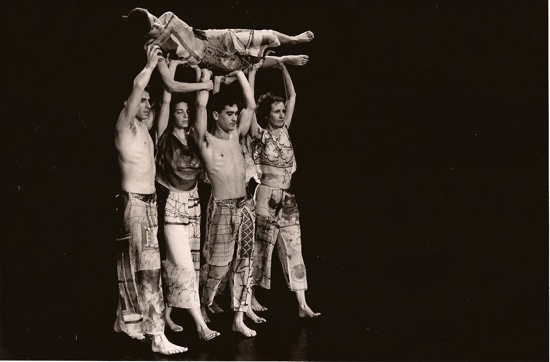

Set and Reset, the original cast: (L to R) Stephen Petronio, Vicky Shick, Randy Warshaw, and Trisha Brown “walk” Diane Madden. Photo: John Waite

The original performers contributed a lot to the choreography. Some of the more unexpected and perilous moments may have crystalized from those improvisations. In every way, Set and Reset is one of the most deliriously slippery pieces in Brown’s oeuvre. The dancers’ joints move as if recently oiled. Their straight arms appear to swing and circle of their own accord. The movement takes simultaneous circuitous courses through their bodies; performers may begin by gently kicking one leg up; when the foot touches ground again, it sets off a current that travels up their spines, rolls into their shoulders, and makes their heads toss, before it snakes down one arm and spills from their fingers. Processes like these are far more fluid and complex that I can make them seem. And all the time, the dancers are stepping, swiveling, springing, and leaping with a nonchalant ease that rarely gives “up” more attention than “down.”

Rarely, too, are more than two people doing anything at the same time. As performers race on and off the stage, they sometimes collide or snag on one another in ways that alter their courses. No one seems deliberately to lift another; momentum results in a hoist that simply augments a jump already in progress. The performers (Tara Lorenzen, Megan Madorin, Leah Morrison, Tamara Riewe, Stuart Shugg, Nicholas Strafaccia, and Samuel Wentz) are wonderfully supple in this soft stew of impulsive-looking activities—tall, slender Morrison (in Brown’s role) in particular. Near the beginning, she races across the stage and is upended, half out of sight, in a running position, by a catcher (Strafaccia, I think) in the wings; at the end, Strafaccia runs to the opposite side of the stage and somehow reverses the same move. Who knows the rules of the game that happens in between?

Actually, that dive isn’t the first thing that happens in Set and Reset. Four people, shoulder to shoulder, hold Lorenzen above their heads. She’s lying on her side, stiff as a board. As they travel along the back of the space, she “walks” on the back wall. The reference is to Brown’s Walking on the Walls, which her dancers first performed at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1971 (they did the job via slings suspended from ropes attached to pulleys and ceiling tracks, and, in the process, turned the laws of gravity into questions). This came out of a period during which the Judson vanguard considered everyday movement a choreographic resource, and structured their dances as tasks.

That Brown would define tasks with more imagination than most of us do was inevitable. At BAM, choreographer-performer Vicky Shick (a member of Brown’s company from 1980-86) re-created Brown’s Homemade (1966). The artist Robert Whitman filmed Brown dancing this solo; she then performed it while a projector (strapped to her back by a brown velvet baby carrier) ran Whitman’s black-and-white, 16-millimeter movie. Shick performs it to a film by Babette Mangolte, based on the original.

The title and the onetime baby carrier are giveaways. The movement suggests a housebound woman doing all manner of little chores and dreaming a bit along the way. These tasks (except maybe the imaginary balloon blowing-up) aren’t literal renditions of anything, but Shick—moving about an area that’s limited by the span of a long electric cord—pats this invisible surface, smooths that one, bends down to scoop something up, talks silently, smiles, points, breaks into an idle soft-shoe bit. Behind her, her tiny film image copies her gestures, sometimes in perfect synch, sometimes not. That little dancer has no spatial restrictions; as Shick turns, her doppelganger tilts, flies around the back wall, leaps out over the spectators’ heads, coasts along the balcony, disappears, then returns. Shick performs the solo wonderfully. The only disappointment is that when a computer was substituted for the mechanism of the projector, no one thought to provide an audio track of the clicking reels. I missed that homey sound.

Newark (Niweweorce) came four years after Set and Reset, bearing different priorities. Its subtitle is the Anglo-Saxon name for Newark, England, but slur the title and you get “new work.” What’s new about it besides its status? Gender and stillness. Brown once said that during a difficult period in her life, she’d begun moving furniture around. That muscular effort and the search for new positions fed into Newark. For those who found her “molecular structures” confusing, Newark, one of the Valiant Series (her term), was easier to parse. Much of the time, the eight dancers put periods and commas at the end of movement phrases. Your eye can grasp designs before they dissolve.

Also, for the first time, Brown distinguished men from women in terms of movement. Against a violently red backdrop, made luminous by Ken Tabachnik’s lighting, Strafaccia and Shugg execute in unison a series of blocky, muscular moves on the floor. They balance on various combinations of feet and hands, upend, turn. Usually in profile, they could be Greek athletes in a frieze. The women (the four from Set and Reset plus Jamie Scott and Cecily Campbell) are softer and more sinuous, except that Riewe seems to function as an artistic mediator—sometimes as straight-forwardly athletic as the men, sometimes more equivocal.

I don’t mean to imply that the women don’t display strength. Strafaccia launches himself and Scott wraps her arms around his legs and holds him airborne, his arms spread, for several seconds. Some of the two-person designs the women create with the men involve difficult cantilevered balances and braced stances.

Donald Judd’s “visual presentation” is a crucial part of the work. Before long, a red drop-cloth falls in front of the dancers. When it lifts, a new yellow wall of fabric has appeared behind them. Over the course of Newark, others will descend and rise—all except a lavender one—in brilliant red, blue, or yellow. The sound concept, too, was Judd’s. Long stretches of silence are punctuated by clunks or buzzes or a blaring somewhat like that of a foghorn. In this changeable climate, the dancers in their gray unitards enter and leave and go about their marvelous work.

Brown’s most recent piece premiered in October, 2011. The BAM performance marked its New York debut (and that of Les Yeux et l’ame). The title is a long one: I’m going to toss my arms—if you catch them they’re yours. (It could even be a satirical reference to dance writing in which body parts sometimes acquire a life of their own.) In Toss, the setting is also crucial. For a woman who began choreographing with no décor except what she found and/or could climb on, Brown has collaborated with a number of major figures in the visual arts. For this last piece of the evening, and of her career, her colleague is artist Burt Barr (also her husband).

Neal Beasely and Leah Morrison in I’m going to toss my arms—if you catch them they’re yours. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

Barr has banked the audience-right side of the stage with fans—all of them mounted in circles (like shallow drum bodies of various sizes) that are set on their sides. These “wheels” vary in their dimensions and color. The largest looks to be about four feet in diameter. They are silver or gold-hued, wood or metal. They gleam in John Torres’s lighting. The dancers sometimes move within this curious forest, and they must pass through it to leave that side of the area. Except for the fans, the stage is stripped to its walls. Anyone needing to cross the stage for an entrance from the other side must walk along the back in plain sight.

On the other side of the stage, in the far corner, Alvin Curran, who composed the music, sits at a grand piano. Part of his evocative score (titled Toss and Find) is pre-recorded, but he begins dropping single notes—later, sweet melodies— into what becomes an increasingly complex texture. From beneath the whir of the fans, continuous and intermittent sounds surface—rumbling, children’s voices, a faint horn call, a harmonica tune.

The dancers begin by swaying, as if undecided as to which way the wind is blowing. At first, they move in unison—leaning, tilting. But soon, various ones of them dash away or break into new patterns. The movement has the Brownian softness and springiness and fluidity, but it’s decisive. The dancers spread space with their arms, cover it with big steps; without violence, they slash and cut the air—their arms and legs swinging straight and pulling them into twists and turns. Often various of them—Beasely and Morrison, say, or Lorenzen and Riewe— move in synchrony; sometimes they all do.

Kaye Voyce has costumed them in white blouses and pants—some cut trimly, others full; occasionally you can glimpse bright colors under the outfits. The reason for this attire soon becomes part of the plot. Neal Beasely, half-hidden behind a large drum, takes off his shirt and comes back into view bare-chested; the fans blow the shirt across the stage. While the dancers ride the wind, their garments do not. As Toss progresses, blouses and pants are gradually shed and drift away. By the end, the men wear only bright-colored trunks and women are clad in what could be bathing suits.

The BAM season inaugurates the company’s new life without Brown at the helm. A three-year international tour titled “Proscenium Works, 1979-2011” will showcase Brown’s major works for the proscenium stage. There are also plans for this period and after it that involve exhibitions, events in museums, and more. Diane Madden and Carolyn Lucas, former company dancers who have been assisting Brown over the past several years, will become associate artistic directors of the Trisha Brown Dance Company, with Barbara Dufty continuing as executive director.

The title for Les Yeux et l’âme came from a line in Rameau’s Pygmalion, when the brought-to-life statue says to the amazed sculptor who created her, “I can see in your eyes what I feel in my soul.” I wished that night at BAM that Trisha Brown could have seen in my eyes what I feel in my soul about her astonishing works—could have seen it in a multitude of eyes, a multitude of souls.

While I was watching Brown’s gorgeous I’m going to toss my arms—if you catch them they’re yours —and minding terribly that it was to be her last—I saw that Riewe seemed to be having a lot of difficulty getting her wide-sleeved, billowy blouse off. In the midst of wishing that the costume designer hadn’t made the garment so unwieldy, I suddenly started to think of the dancers gradually divesting themselves of their clothing as a metaphor for Brown divesting herself of her dances. Let them go, dear Trisha. They will be honored. They will be cherished.

“I’m going to toss my arms” was performed here in Portland, minus the grand piano I’m sorry to say. The shedding of clothing that Deborah describes as a “metaphor for Brown divesting herself of her dances” brought tears to my eyes, and I will now never be able to watch the “birds flocking and fluttering in an urban landscape” that occurs every afternoon outside my living room windows (usually crows, lots of crows, and seagulls) without thinking of “Set and Reset.” Thank you Deborah, from my heart to yours.

Trisha Brown’s work and her bevy of talented dancers throughout the years have shaped the perceptions of generations of choreographers and dancers that have followed. The tools choreographers and performers use to create dances and their perceptions of relating to space have forever been changed by TB’s dance experiments. I’m quite sure there is a brand new generation of dancers using those same tools that are mostly unaware of the origins of their craft.

In my formative years, TB’s work and her dancers [via countless workshops] inspired me to become both a dancer and choreographer. And although I left the dance world 5 years ago, I am reminded of this and why I love crafting space so damn much, each time I have the opportunity to see her company perform.

When the curtain came up on “I’m going to toss my arms….” I was completely drawn in. The deconstruction of the space combined with the exquisite dancing and music made me feel as if I was home again. Her last piece [and goodbye] was a perfect synthesis of where she’s come form and where she’s heading. Thank you Trisha Brown.