Audience members as Bradley Teal Ellis’s family in his (american) guilt (Mom’s bouquet missing). Photo: Ian Douglas

Neal Beasley and Bradley Teal Ellis staged their joint appearance on one of Dance New Amsterdam’s SPLICE series more intimately than other choreographers sharing a SPLICE program have done. They took the word “splice” seriously—dividing Ellis’s (american) guilt and Beasley’s every adam belonging to me into three parts, and splicing them into each other in alternating segments. They evidently saw, too, the kinship of their pieces—the way both examine in very personal, oblique, and fragmented ways the business of growing up gay in America.

To make the boundaries between their works more porous, the two have blocked off the usual seating area in DNA’s black-box theater; a few chairs and a sofa are scattered around; a scene may be performed in front of you in one part of the evening and necessitate your turning around or closing in for the next one. You can sit on the floor, stand, or wander like medieval spectators trekking between the wagons lined up to show miracle plays. You may end up as a performer’s backdrop.

I begin, for instance, with a side view of Ellis’s spoken introduction of three selected-in-advance spectators (all women the night I attended). When he has done talking about his lack of family photographs and getting another viewer to snap his portrait with those he has designated as his mother, father, and brother, he arranges them for a grimmer family image. The parents he crowns with tall black hoods shaped like the ones Klansmen wear and puts a wrestler’s mask on the kid. He gives “Dad” a flag to hold and “Mom” a bouquet. He centers “Brother” in an empty frame. Then, stripped to jockey shorts and zipped into a sequined, gauze-fronted hood, Ellis dances—wilting but determined—on the floor in front of the tableau. (If I were one of the volunteers, I’d be panicking now.) I walk around to view the scene head on. From that angle, Amanda K. Ringger’s most powerful light is behind the three, and you see them as dark, looming, haloed figures.

Beasley, too, begins with cultural (and maybe family) history and explanatory clothing. Tossing garments from a bag, he opts for half-on overalls and boots and—to the faintly heard, immediately ironic sweetness of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto in D—corrals himself by wrapping clothesline around a ladder and one of the room’s pillars. Disguising himself with a curly gray beard and toupee (his inner grandpa?), he moves slowly around, bracing himself against the ropes, caressing himself, while a recorded voice (his), speaking with the drawl of his native Missouri, fulminates about the vanished frontier and the disappeared wilderness-bred American, and about the mythic figures of manhood like Pecos Bill that are held up to growing boys.

Ellis has ropes too, but thicker ones, and—in front of a hanging flag-cum-quilt made of plastic bath mats—he and Rafael Botana (also wearing jockey shorts and a dressed-for-the-party s & m hood) gravely take turns aiding each other in winding rope around themselves. Sometimes the designs are ingeniously tricky, sometimes more obviously bondage (a bit too obvious when a rope end becomes both a penis and a whip). Another volunteer spectator watches their ritual. They’ve draped her in a long cloak and a collar with balloons floating from it. She plays her role with endearing dignity, occasionally yielding to small, embarrassed smiles and questioning glances and endeavoring not to wince when the men pop the balloons with lances to shower her with glitter.

Beasley’s experience is darker. Wearing a hoodie and holey jockeys, he pushes the stepladder to face the room’s wall-to-wall mirror so we see both him and his image. His stuttering, mumbling, cursing, dead-drunk voice accompanies his futile attempts to. . .what? Climb the steps? Stay on his feet? Splayed, hanging off the ladder, his voice shatters into gibberish. Something very bad is happening to him.

Compared with him, Ellis and Botana blaze with louche self-confidence, which their hoods reinforce. They saunter and pose as if a Hustler photographer might happen by at any moment. They lounge on a couch together, but watch each other dance appraisingly. When John Hoobyar joins them, they unhood for a three-way bout of contact improvisation. Now we see them, and the posing is done. Three relaxed, comradely men dancing sensually together. Cue up the sunset.

No such unequivocally happy ending for Beasley. He too takes off his disguise. In jeans, a white tee-shirt, and a baseball cap, he pulls a tiny red wagon under the ladder and sets a potted hyancinth beside it. His voice mutters barely intelligible, sexually-charged phrases (“sucking red-neck cock. . . .” Did I hear that?), but also, “I won’t let you love me the way you want me to.” Gradually—manifesting all the subtle skills that make him such a fine performer in Trisha Brown’s work—he disintegrates, as if things under his skin were making him itch, eating at him, bite by infinitesimal bite. His fingers wiggle, his feet stagger. What is he sloughing off? Finally he uproots the plant and hurls all the accumulated clothing into the fallen ladder. The room goes silent and dark.

This is the kind of very particular, small-scale, experimental performance that you walk out of saying, “What was that about?” Then you sort of know. Then maybe you don’t. Anyway. . . .

Igor Stravinsky’s monumental Le Sacre du Printemps celebrates its 100th birthday this year. Few works choreographed to it since have generated the excitement and derision that the music and Vaslav Nijinsky’s ballet incited in 1913. Many virgins have danced themselves to death over the years, and the public’s aversion to dissonance in both music and dancing bodies has waned.

The sacrificial virgin had no control over her fate, but several choreographers since Nijinsky have chosen the role for themselves and danced not just to the final solo as it appears in the original scenario, but to the score’s entire 32 or so minutes. Molissa Fenley presented herself in a heroic ordeal in State of Darkness (1988). Tero Saarinen in his 2006 The Hunt danced as prey, camouflaging his body with projected images. The noted Australian choreographer Meryl Tankard, whom Americans probably know best as a remarkable member of Pina Bausch’s Tanztheater Wuppertal for ten years, has entered the lists with The Oracle. She doesn’t perform the solo herself but conceived and directed it, leaving the dancing to her co-choreographer, Paul White.

White, who (perhaps coincidentally) joined Tanztheater Wuppertal last November, is a stunning dancer, and the choreography spares him nothing. The Oracle, a powerful piece of theater, traffics in ritual, mystery, and ordeal. Yet sometimes its coherence founders in the immensity of its self-proclaimed vision. An interview with White and descriptions in the press material mention a struggle between man and the forces of nature, between strength and vulnerability, and between masculinity and femininity. White also mentioned foreseeing the future, and it’s the title of the piece that influences my perception as I watch him leap and writhe. The Pythoness at Delphi and other sacred oracular beings of ancient Greece often suffered as they dragged their visions and predictions into the light.

Tankard sets up Stravinsky’s ordeal with a media presentation by Régis Lansac. To part of a Magnificat by Joao Rodriguez Esteves and a selection from Jean Christophe Frisch’s Musique des Lumières, Lansac floods the backdrop with troubling projected images of White. Fragmented symmetrically, as if in a kaleidoscope, his twin faces merge and crumple into what could be a malevolent gnome; his hands and arms multiply; he becomes a mandala.

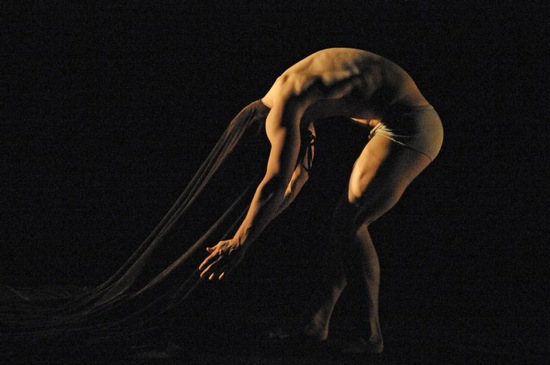

When Stravinsky’s music begins, White embarks on one of The Oracle’s most potent sections. He draws over his head a piece of black cloth. The fabric is strangely supple, inky in the light (lighting by Damien Cooper and Matt Cox). It conceals White’s face and hangs forward from his head like long, long hair that he can drag and swing about. He ripples along the floor, humping his back like an inchworm. The fabric becomes, briefly, a headdress, then a skirt.

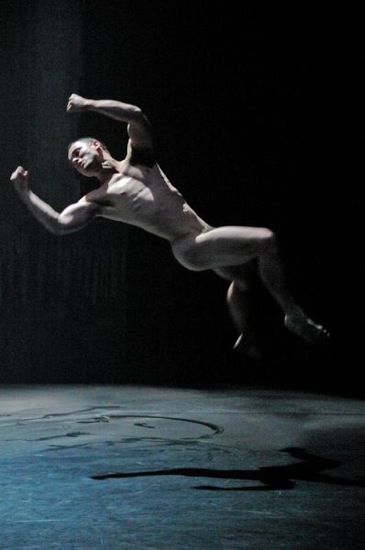

Various projected images continue (for a bit too long) as White dances—once in a ragged, golden skirt, eventually naked—always in extreme ways. Blackouts separate sections. The music that Stravinsky wrote for the dance of the “Chosen Maiden” culminates White’s ordeal. No more ceremonious ritual. He’s running, staggering, jerking, lunging. He’s leaping—flying. He’s spinning and cartwheeling, the full skirt that he’s donned forming circles in the air. When he pauses, bent over, breathing hard, the light pours down on his muscled back. Sometimes he’s almost too good—still in control of his pirouettes. Still, we’re watching a dancer kill himself for us; our blood is up. That, I guess, is the point. During White’s final explosion into the air, he disappears into a flash of brilliant white light followed by darkness and silence. Then applause. Sober, exhausted, White re-materializes to bow to a cheering crowd.

One of the things I’ve always liked about the ending of Paul Taylor’s version of Sacre is the ambiguity. As he flips between the Chosen One as a grieving woman, a singular sacrifice and just another member of the corps, he reminds me of all the roles that the music has played in our culture since its premiere. I’ve seen as many versions of the dancework as have come my way, and am always curious to know about others. Many thanks for reporting back on Tankard’s work.

I cannot think of many critics – Dance or other – that can so vividly evoke with their prose and their passion for the art the excitement of a performance. Thanks, Ms. Jowitt.