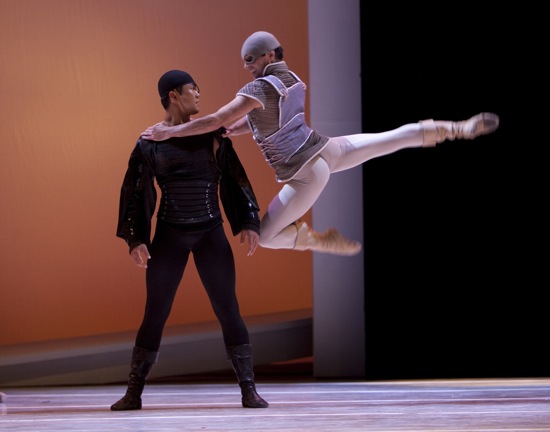

Carla Körbes and Seth Orza of Pacific Northwest Ballet in Jean-Christophe Maillot’s Roméo et Juliette. Photo: Angela Sterling

Lincoln Kirstein has written that while the New York State Theater (now the Koch) was under construction, George Balanchine wandered in and saw that the pit would hold no more than 35 musicians. He immediately threatened to withdraw the New York City Ballet as the principal designated tenant. The pit was redesigned to accommodate 70 players.

Had Balanchine, to whom music was so important, visited City Center during the Pacific Northwest Ballet’s recent season, he would, I’m sure, have been overjoyed to hear the scores for three of his greatest ballets, Concerto Barocco (1941), Apollo (1928, and Agon (1957), played so superbly by the company’s orchestra, under the accomplished and dance-sensitive baton of Emil de Cou.

Bach and Stravinsky, had they strolled from the spirit world with Balanchine, might have been equally entranced.

PNB’s women in Balanchine’s Concerto Barocco, Front: Laura Gilbreath (L) and Lindsi Dec. Photo: Lindsay Thomas

As you might expect, the dancers in Concerto Barocco and Agon (staged by the company’s Founding Artistic Director) and in Apollo (staged by PNB’s current Artistic Director, Peter Boal) perform with musical aplomb and accuracy. In Barocco, the eight women of the ensemble bring a breezy crispness to the opening vivace movement of J.S. Bach’s Double Violin Concerto in D minor, and they calm themselves sweetly down into the sisterhood that forms bowers and arbors for the female soloist and her partner (who has fortuitously arrived just in time to replace the second leading woman and make the largo movement into a blissful courtship). From the front row of the loges, you have the heady experience of seeing both the two dancers weaving through the corps de ballet and the two solo violinists (Michael Jinsoo Lim and Brittany Boulding) doing the same with the Bach’s string ensemble.

It’s possible that Lindsi Dec, Laura Gilbreath, and Batkhurel Bold were experiencing a slight case of opening-night nerves in the New York City Ballet’s hometown, where Concerto Barocco has had a long history. They danced finely, even expansively, but seemed slightly reined-in. At that pungent moment in the duet when the woman, grasping the man’s right hand in hers, pulls slightly away from him and then toward him again, I missed the intensity of the connection between Galbreath and Bold, and when she traveled around him while he stood facing front, he was as implacable as a pillar, not seeming to sense the woman whose hand he held. Yet the clarity and gentleness of all the dancers in this movement was lovely to see.

Seth Orza as Balanchine’s Apollo with (front to back) Carla Körbes, Maria Chapman, and Lesley Rausch. Photo: Lindsay Thomas

Let me now switch to the present tense. I owe it to Carla Körbes, who dances in Apollo as if unconcerned with yesterday and unafraid of tomorrow—that is, without a trace of mannerism, she fills each passing moment and shapes each phrase as if she understood and cherished it. She is the Terpsichore to Seth Orza’s fine, boyish Apollo, and you could see why he chose her as his principal muse over the handsome Calliope of Maria Chapman and the charming Polyhymnia of Lesley Rausch. Balanchine, of course, weighted the competition in favor of Terpsichore, but that’s not what I mean.

In this ravishing and stirring little ballet (a quartet in Balanchine’s shortened version), the god and the muses are young and frisky—teenagers perhaps—and the ballet takes place in those threshold moments when Apollo and his companions are readying themselves to take their places on Mount Olympus (when the summons comes, you can hear it in the music and see it in his demeanor). He’s been testing his own powers and his ability to master these three fillies as if he were yoking them to his artistic chariot. But when he tires or loses confidence, they’re ready to play the big sisters and let him lay his head in their hands.

What Körbes brings to her performance as Terpsichore beyond musicality and beautiful line is her sense of wonder and discovery. This has partly to do with her focus. When she lies on her belly on Orza’s bent-over back as he kneels for the sequence that aficionados know as the “swimming lesson,” she looks far beyond her gently breast-stroking arms as if taking in the seas beyond. At the end, Apollo and the three muses walk around the stage to arrive at their final sunburst pose, while Stravinsky’s music is climbing the stairs they used to mount in the earlier version of the ballet. Chapman and Rausch, of course, look where they’re going, but Körbes’s gaze takes in the space she’s traveling through on this great adventure, and what might be stars just above the horizon. This isn’t just a matter of where her eyes are focusing. It’s an act of really seeing—with the entire being.

(L to R) Kylee Kitchens, Jonathan Poretta, and Elizabeth Murphy in Balanchine’s Agon. Photo: Lindsay Thomas.

It was musically exciting on the part of PNB to follow Stravinsky’s neo-classical score for Apollo with the denser, more astringent music that he wrote for Agon almost 30 years later. You return from intermission to find the pit stuffed to overflowing; winds, brass, and percussion instruments, harp, piano, and mandolin have joined the string players.

The controlled brashness of the four athletic males who open the piece acts as a fanfare for Stravinsky’s made-in-America hymn. Not that the two ensuing trios, the pas de deux, and the sections performed by the twelve who make up Agon’s cast aren’t mannerly. The composer named the sections after baroque court-dance forms, such as the branle, the galliard, and the sarabande, and Balanchine honored that formality, even as he skewed it off balance.

Kylee Kitchens and Elizabeth Murphy aid lively Jonathan Porretta in the first pas de trois (I appreciated Murphy’s forthright enthusiasm). Andrew Bartee and Jerome Tisserand ace the fiendishly close canon in their duet in the second pas de trois and as partners for Chapman. Rausch comes alive in a pas de deux that necessitates extreme flexibility on the woman’s part and excellent timing on the man’s, and steady nerves for both. “Hmm,” you imagine Balanchine thinking as he choreographed, “what if he’s supporting her in arabesque on pointe and suddenly he falls to the floor without releasing her hand or knocking her down?” Watching this moment, you still hold your breath.

In PNB’s too-short season at City Center, the Balanchine program was given only once; the remaining three performances were devoted to the company’s production of Jean-Christophe Maillot’s 1996) Roméo et Juliette, which was seen in New York in 1999 when the Ballet de Monte Carlo brought it here. I can understand why Boal chose to add it to PNB’s repertory. It suits the performers, it doesn’t stand on ceremony, it’s full of dancing, and its Romeo and Juliet behave like lusty teenagers—healthy young animals at play, with shyness and boldness tugging them this way and that. And Prokofiev’s score is a great one.

Friar Laurence (Karel Cruz) with his acolytes, Jerome Tisserand (L) and Andrew Bartee in Maillot’s Roméo et Juliette. Photo: Angela Sterling

I can’t decide whether it’s better to know Shakespeare’s story well enough to fill in the blanks or not to have read it and make up the details from what you see. Who can be sure at first whether that tall, reserved fellow is Paris (Joshua Grant), the Capulet’s chosen suitor for their daughter, or a wimpy version of Capulet himself? But no, Lady Capulet (I saw Gilbreath in the role) wears widow’s weeds, albeit slit up the side; it’s just that she seems to have the hots for Paris herself, as well as for her nephew, Tybalt (Bold).

Maillot had the fanciful idea of making Friar Laurence (William Lin-Yee, substituting for Karel Cruz on opening night), a kind of Greek chorus. He has to fulfill his role in the plot (marry the pair, give Juliet something to make her appear dead), but he also slinks around suffering, because he knows what’s going to happen but can’t stop it. He even masterminds a puppet show with obvious Capulet and Montague protagonists, but the families watching it in the public square don’t get his point. He travels with two “acolytes” (the estimable Bartee and Tisserand). Does he feel an anguished backbend coming on? They’re there for him.

This Verona, designed by Ernest Pignon-Ernest, is a handsome Frank-Gehry-manqué affair of curved and straight and slanting white surfaces, with panels that move to convey different locales. Romeo (Orza) strangles Tybalt (in a mighty struggle) on the same ramp that Juliet slides down to meet her lover for what we know as the Balcony Scene. Dominique Drillot’s lighting turns the stage sunny or ominous or moonlit. Jérome Kaplan’s costumes fit the modernist look of the stage; they’re relatively plain (except for Juliet’s shimmering gold party skirt), very becoming, and muted in color.

There are some nice dramatic touches. Rosaline (Chapman), far from being the girlfriend who spurns Romeo and disappears in the first scene, is a party girl who sees no difference between Montague men and Capulet men; they all have tights. The fateful scene in which Tybalt kills Mercutio (Poretta) and Romeo kills him in return starts out with the rival gangs moderately amicable, mingling in the village piazza until a chance word or gesture acts as a spark to the abundant underlying tinder of hostility. Juliet, on learning of Tybalt’s death at Romeo’s hands, opens her mouth wide, like an infant, in two silent howls. Although Friar Laurence doesn’t give her a sleeping potion (his touch seems to be enough to daze her), Romeo, in the moment when he tries to see if any “poison” remains for him on Juliet’s lips, draws her whole inert upper body up with a kiss, as if he’s trying to suck her soul into life or himself into death. When he lets her go, she drops back onto the “bed” (another slanted platform), and he falls away from her, huddled into his grief.

Prokofiev’s glorious music, eloquently played, tells us much of what we need to know about this society, these characters, and their feelings. Maillot’s choreography follows its lead, but not always its ambiance. In his effort to emphasize the vigor of its townsfolk (almost everyone in this town seems to be under 21), he has the ensemble dancing almost constantly. They leap and pirouette; the men throw the women high in the air. These are Capulets and Montagues on speed; they don’t spend much time sneering and spitting and making rude gestures—or wrestling, for that matter. And they rarely take stock. The choreography rolls on with almost an aerobic zest.

The heart of the ballet is the dancing for Romeo and/or Juliet. Körbes and Orza play a couple of teenagers so full of inexplicable lust and delight in one another that they flirt and tease until shy abandon gradually matures into love. They’re not proper at all. She stands, feet planted, and he dives onto his belly and slides between her legs and past her. She backs away from his attempts to kiss her, but quickly learns the strange feelings that a caress can stir up now that she’s—what?— 14. A curiously significant but awkward motif in which the two join their palms and make them undulate together seems to indicate both the flame of their passion and the precariousness of their future.

I regret not seeing the other cast (Kaori Nakamura and James Moore), but Körbes and Orza (both former NYCB dancers) perform with endearing frankness and ardor, nuzzling like puppies. In the end, it is their dancing and acting that moves you the way Shakespeare’s words do. Maillot made some of the roles less nuanced. Lady Capulet is more a slinky bitch with a low boiling point than a stern parent. And the nurse (Rachel Foster), conceived of as young, is almost a caricature of zealous bustle in the early scenes. Mercutio might have been made to order for Poretta. What a devilish imp he is! And Benjamin Griffith’s Benvolio is more mischievous than this character usually seems in other R & J ballets. Bold isn’t the sly, snaky Tybalt we often see, or the haughty one. He’s strong and solid and he knows what he wants. Because Bold comes across as earthy, it’s an especial pleasure to see how nimbly and incisively he flashes his legs in the air and what a fine, soaring leap he has.

Having seen these New York performances, as well as Pacific Northwest’s Ballet’s Giselle in its home city, I hope the company doesn’t wait too long to pay us another visit.

Wow, great article post.Thanks Again. Fantastic.