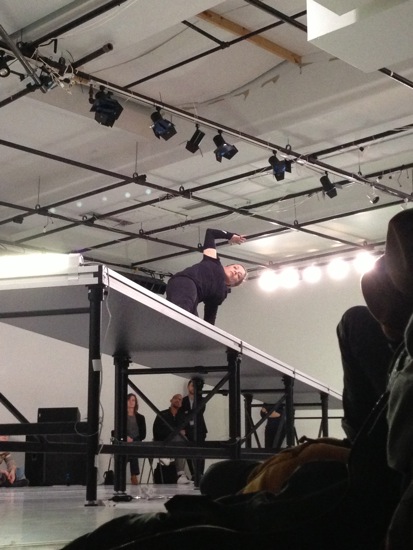

Myriam Gourfink in her Breathing Monster at the Center for Performance Research. Photo: Damien Valette

You’re informed by program material that the compellingly idiosyncratic French choreographer Myriam Gourfink works with scores, sometimes with computers, in devising her dances, and that the breathing techniques of yoga are fundamental to her process. You learn that she is concerned with the “micro-movements” affiliated with breath and how these infinitesimal inner adjustments conspire to move her through space. All this projects to the spectator as uncannily extreme slowness on the part of the performer, as well as a pungent duality. In her Breathing Monster, Gourfink seems to be nearly weightless as she moves her body and limbs fluidly through complex trajectories. At the same time (say, when you watch her support herself on one foot and one hand and slowly, slowly move her other leg from behind her to the front and place it down on a surface), you’re aware of the enormous effort and control her journey demands.

Breathing Monster constitutes one of two programs of Gourfink’s choreography presented by Chez Bushwick on January 11 and 12). The piece’s combination of austerity and sensuality is set off by the whiteness of the Center for Performance Research in Brooklyn. White walls, ceiling, floor. For Breathing Monster, some of the usual seating is pushed back, and the limited audience that surrounds the performing area makes do with scattered chairs or the floor. Near one corner, composer Kasper T. Toeplitz is situated on a low platform—his laptop open, his electric bass at hand. When we enter, Gourfink is already in place. Wearing dark brown tights and top (each decorated with a single snaking white line), she sits at one end of a trail of long, narrow, white-topped tables joined together. Fluorescent tubes attached to the first and last tables denote the beginning and ending of a path about three feet off the floor. Although she sits perfectly still, her legs hangings over the edge of the first table, the long, empty stretch at her left suggests a vacuum to be filled, a road to be taken.

And she begins. Toeplitz starts softly massaging the strings of his bass, creating a distant rumble that gradually gets louder and begins to pulse. That Gourfink is traveling along the tables is clear, yet her forward momentum is barely perceptible. She’s attentive to her body. Her inaudible breathing gradually impels it to bend, causes one arm to reach up and over to touch the table, her weight to shift. By the time a number of seconds—maybe minutes?— have gone by, she has twisted and inverted herself so that her cheek is on the table and her rump is in the air. And she’s still evolving. Breathing Monster lasts for 46 minutes.

Breathing Monster in a performance in another site. Photo: Nicolas Chaussy

Close to Gourfink in the small space, you have time to focus on details, such as the way she sometimes braces herself on a tent of fingers, rather than on her palm. When she pauses for a second, her weight supported on both hands and feet, her body facing the ceiling, you can watch her belly swell and subside with her breath. As one of her legs gropes through the air, her toes separate and wiggle slightly, as if sensing the climate surrounding her foot’s destination. And, of course, you can wonder what that immediate destination will be. For all her calm, unstressed flow, the performer generates a kind of suspense. Once, when she has finally placed a hand on the next table, I’m sure she will move onto it, but, no, in order to assemble herself correctly, she has to backtrack a bit.

She never stands. Rarely does she linger in a position. Seldom do we see her face, so complex are her convolutions, so minimal the adjustment in her flow. Sometimes she gazes upward, and it’s tempting to imagine her a torpid monster emerging from its winter burrow, with a force above her causing her to stay close to her “ground.” Once, at the boundary between the third and fourth table, she rotates and re-settles with comparative swiftness. It’s almost shocking.

Toeplitz gives her an environment that changes subtly. Little percussive tickings, pockets of silence, the sound of a bow on strings, a squeaking like that of a rubbed balloon. At the end of the allotted time span, he reverts to the rumble he began with and makes it gradually diminish. At the exact moment that she reaches her destination, the sound finds silence.

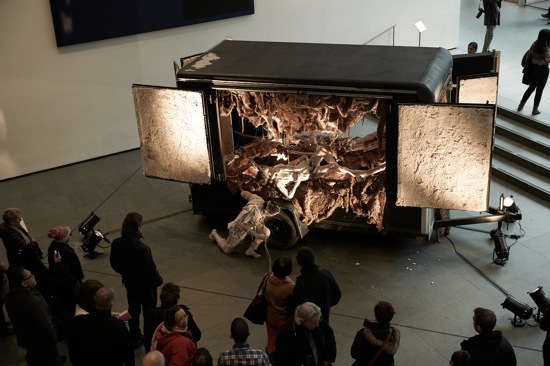

Koma of Eiko and Koma in The Caravan Project at the Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Anna Lee Campbell

Slowness and endurance are integral to the work of Eiko and Koma, but their creeping pace is occasionally interrupted by occasional tiny, quick adjustments or a sudden minimal shift of weight in deference to gravity. They sometimes seem to be erupting from the earth, where they’ve been buried for centuries. Earth, piles of leaves, tree trunks, water—they can inhabit them all, become one with them.

These remarkable artists of the body have been revolutionaries for years. During the 1960s in their native Japan, when students and artists made rebellion a way of life, they might ride into their performances on a motorcycle and race away afterward. In 1999, they figured out a way to expand that idea and reach an audience that mightn’t be able to afford theater tickets: The Caravan Project. Inspired by Joseph Cornell’s small boxes with magical worlds inside, they drove to appointed parks or other sites in a Jeep Grand Cherokee, pulling a trailer that could be opened on all sides to create a small performance space. No one paid to see them; you could happen upon them the way you’d happen upon an interesting tree or flower.

The Caravan Project at MOMA. Photo: Anna Lee Campbell

In connection with the Museum of Modern Art’s current exhibition Tokyo 1955-1970: A New Avant-Garde, Eiko and Koma parked their trailer in the museum’s front lobby and during museum hours between January 16 and January 21, they perform in it for seven hours a day (longer on Saturday). If one of them needs to leave for a short rest, museum attendants are on hand to drape blankets over him or her, but the trailer is never uninhabited. You have to pay the museum fee if you want to get close to them, but they can be seen from a distance for free.

I make it to their last performance on Martin Luther King Day. It has attracted a larger crowd than usual, but there’s still room to move around the trailer and get new perspectives, to sit on the floor for a while, or go up into the galleries and look down at the scene. You can go away and come back. In fact, you have to pass the trailer in order to get your coat and leave the building. Some people watch for hours at a stretch.

Eiko rising. Photo: Anna Lee Campbell

The trailer’s interior is draped with—stuffed with—a fuzzy, loamy, brown substance that hangs like Spanish moss or puddles around a rear tire; small dead leaves and twigs and grass stems adhere to it and to the two performers. Eiko and Koma look as if they’ve been dug out of a bog. Their garments are ragged, and their heads and faces are covered with what might be ripped cheesecloth; it mashes their features. Lights—including a buried one that Koma uncovers—cast an amber glow over this nest.

These elemental creatures move by increments. What are they trying to accomplish? Perhaps simply to exist. Individually, they worm their way onto the edge of the trailer or sink into its central well and disappear. They grasp tree limbs shorn of bark and hang precariously out of their refuge, gazing into a distance they seem not to see. Once, Koma leans out so far that he falls to the floor with a thump pronounced enough to make nearby spectators wince. Once, he stands on his toes on the trailer’s hitch platform, reaches to the vehicle’s roof and jiggles futilely on his toes, struggling, apparently, to climb up there. Several times during the hours that I watch them, Koma laboriously crawls to Eiko and nuzzles his face into her neck or burrows his head into her spine. Sometimes she seeks him out. Occasionally one of them gropes for and grasps the other’s hand. But no act can be interpreted for sure as premeditated or conclusive.

Eiko and Koma. Together. Photo: Anna Lee Campbell

Guards will stop you if you step over the taped lines, but you can still see the pair at close range, whether through the wide doors open on either side or the narrower, half-open end ones. And you can be moved by this strange, numb drama that seems to go on forever; although one moment is never identical to any other, all fundamentally convey an inevitable and never-ending struggle to find comfort, succor, and rest—or perhaps just to survive. Watching Eiko’s preternaturally long toes reaching to touch the floor or seeing her drowse, draped along the trailer’s edge, you think she could be a hundred years old. “Who are they?” people ask. “No,” a man says to his wife, “they’re not mechanical, they’re real.” Some viewers are mesmerized, others puzzled, others disturbed. A small tide of people swirls randomly around the trailer, ebbs, swells again.

In the last five minutes of the last day of this extraordinary performance installation, Koma, walking slowly and with difficulty, closes all the openings, gently pushing Eiko’s head back inside. Then he clambers arduously onto the trailer’s roof. No jeep comes to drive it away.

I have been browsing online more than 4 hours today, yet I never found any interesting article like yours.

It’s pretty worth enough for me. Personally, if all website owners and bloggers made good content as you did, the web will be much more useful than ever before.|