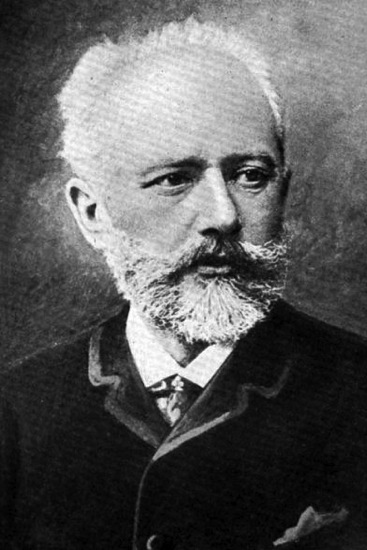

George Balanchine once said that during his grueling years as a pupil in the Imperial St. Petersburg Theatrical School, he didn’t fall in love with ballet until he was twelve. The change occurred the first time he appeared onstage in Marius Petipa’s Sleeping Beauty, set to Peter Ilyitch Tchaikovsky’s ravishing score, and young Georgi Melitonovitch was cast as a Cupid. His arrows, so to speak, boomeranged back, and he was smitten.

Tchaikovsky remained Balanchine’s favorite Russian composer (barring Stravinsky, of course), and the works that he choreographed for the company we know as New York City Ballet introduced audiences to aspects of Tchaikovsky’s music they mightn’t otherwise have discovered. What better reason for the company to devote the first two weeks of its season to ballets set to Tchaikovsky’s music? Of the ten ballets on view, nine were Balanchine’s and the other, Bal de Couture, a premiere by Ballet Master in Chief Peter Martins.

You could think of Serenade, Mozartiana, and Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 2 (the ballets on the opening program) as commemorating different stages in Balanchine’s relationship to Tchaikovsky. Balanchine began to choreograph Serenade less than six months after he arrived in New York, at Lincoln Kirstein’s behest, to found a school and company. Although, he had always loved Tchaikovsky’s Serenade for Strings and gave no deep reasons for his choice of music, it’s tempting to note that his first ballet on American soil was set to a piece by the very composer whose music had accompanied his first appearance onstage decades earlier.

Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 2, in its early incarnation as Ballet Imperial (1941—an homage to Petipa and Russian classicism, with its backdrop of the Neva River) established New York City Ballet’s presence in the just-opened New York State Theater in 1964. Balanchine made his first Mozartiana, set to Tchaikovsky’s Suite No. 4, Mozartiana, Op. 61, in 1933 and the current one for NYCB’s Tchaikovsky Festival in 1981. It was one of the last ballets he choreographed before he died, and its images—which had always implied a death—issued from a different perspective and acquired a different resonance.

January 16, the second night of the season, featured the debuts of several dancers in new roles. In Serenade, Sara Mearns and Megan LeCrone appeared for the first time. The performance also marked Mearns’s return to the stage after spending eight months recovering from a serious back injury. When she entered at the reprise of the opening ensemble passage (reenacting a dancer’s late arrival at a 1934 rehearsal) and struck the other women’s gesture of warding off imagined sunlight, the tears usually summoned up in me by the swell of the music and the poignancy of the image came close to flowing.

Watching this splendid performance of Serenade, I marvel again at how, for instance, Balanchine uses running in this ballet. The romanticism of Tchaikovsky’s Serenade for Strings in C major, Op. 48, inspires a patterned rushing about by cadres of women. Their long blue dresses flutter like a storm of leaves as they tear on, off, and around the stage, and those moments when they calm down or coalesce into sisterly groups seem almost miraculous. Mearns’s composure on this night is truly miraculous, considering that her comeback is also a debut. As always, she dances with a voluptuous fullness, surrendering herself to the moment. You’d never guess her pliant spine had known a moment of pain. Luring her noble partner, Jared Angle, around the stage in a darting passage, she doesn’t just look behind her to see if he’s following; her whole being seems to yearn back toward him even as her steps propel her forward. I’m sure Mearns will become even finer the more she dances in Serenade (the only moment when she betrayed nervousness at her first performance had to do with her timing in letting down her hair for the last section).

Megan LeCrone also made an auspicious debut in the role of the guiding angel who covers the eyes of the mysterious traveler (Adrian Danchig-Waring) in one of the enigmatic traces of narrative that seep into in this “storyless” (Balanchine’s term) ballet. Ashley Bouder is an old hand at the erupting jumps and leaps of the more ebullient woman. Her full, sheer skirt, which has a disconcerting life of its own, does its best to tangle around her; she triumphs.

Sterling Hyltin is making her debut in the ballerina role in Mozartiana. This is also Chase Finlay’s first time in the work. Hyltin projects a lovely delicacy but her dancing also has amplitude and force, and Finlay is an elegant prince to her princess (I sometimes feel a slight stiffness in his neck). In Mozartiana, Tchaikovsky alluded to several works by Mozart and one by Gluck, and although the music is clearly of the 19th-century, Balanchine’s “Gigue,” wittily danced by Anthony Huxley, has the manner and the nimble footwork of 18th-century dance (the bows on his shoes are a nice touch).

For Serenade, Balanchine switched the order of Tchaikovsky’s three movements to end his ballet with a stunning apotheosis. For the 1981 Mozartiana, he put the “Preghiera” (Tchaikovsky’s response to Mozart’s motet Ave Verum Corpus) first. In this prayerful sequence, the woman (Hyltin) does almost nothing but bourrée. Her tiny twinkling steps on pointe carry her here and there as if she were born on a current. But there’s nothing simple about the brilliant solos with which she and her partner challenge each other. My memory of the 1981 premiere is that this woman (originally Suzanne Farrell) first appeared surrounded by four tiny girl attendants (students at the affiliated School of American Ballet) in black dresses. In this production, the very adroit children appear later, and it’s four similarly clad full-grown women who are onstage after the curtain rises. I liked the shock of the earlier version; Farrell looked like a distraught court lady amid Lilliputians. Either way, you can imagine the two sizes of females as representing the transition from SAB students to NYCB dancers—a process that began with Balanchine’s first years in New York and continues today.

A fine letter that Simon Volkov wrote to Balanchine is quoted in the NYCB program. In it, he says that Mozartiana “does not follow the music, mirroring its meter and rhythm. It draws the music into a complex counterpoint.” Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 2 is much more exact in its relationship to the music and in its decorum. Still, the music wasn’t written for ballet, and the interaction between the orchestra (led by guest conductor Roberto Minczuk) and the piano (excellently played by Susan Walters) can seem like a bold and florid conversation.

The opening movement suggests a grand party. How ingeniously eight men take charge of helping 16 women! But the behavior is less ceremonious than that in a Petipa ballet. The leading dancers, Teresa Reichlen, Tyler Angle, and Ana Sophia Scheller (the latter two performing these roles for the first time) don’t exactly barge into solos and a duet, but neither do they introduce these with a watch-me hauteur. Some of the passages are as ripplingly tricky as the piano’s cadenzas; Reichlen dances her intricate solo with aplomb, and Angle executes his with the natural princeliness that often marks his dancing. Brisés volés become a pleasantly exacting pastime instead of an exertion. When the orchestra kicks in as the two leave the stage together, it sounds as if the instruments were applauding them. Scheller is charmingly piquant as the second leading woman, frolicking amid the two demi-soloist couples and the woman-dominated corps de ballet. She has a beautiful line—clear and open.

My own favorite part is the Andante. The ballerina, as if temporarily tiring of the duet, leaves the stage. Her bereft partner is immediately consoled by chains of women who take his hands on either side. He pulls them forward and back (they bouréeing as they go), as if he’s wielding giant wings made of women. His lady returns, and they dance together some more, but she can’t stay. He raises his arms, and his attendants return.

Balanchine makes you listen to music in ways you’ve never heard it in a concert hall or lounging with an iPod.

hallo – as always i read with great appreciation your so sensitive reviews and points of view….

however…..

if you say TCHAIKOVSKY was Balachine’s favorite russian composer

– where does that leave Stravinsky who was a world traveler but kept russia as very much a part of his musical background and whom Balanchine worked extensively. maybe they would both win a tie as balanchine/s favorite russian composer(s)

I had the same thought, actually.

I love the description of this performance of Serenade, a ballet that played a huge role in the lives of Todd Bolender and Janet Reed–the former, who had been studying with Hanya Holm and was far more interested in modern dance than ballet in the early Thirties, wanted to work with Balanchine after he saw it the first time. While he never as far as I know danced in Serenade, he did understudy William Dollar in what was then called Ballet Imperial on the 1941 South American tour, and said many times that nobody ever matched Marie Jeanne in the ballerina role. Reed, however, danced the “searching girl” many times after she made the shift from Ballet Theatre to City Ballet in 1949, at Balanchine’s invitation.

Joel and Martha were right to bring up Stravinsky, and I’ve since added a parenthetical reference to him in my post. However, Balanchine told Simon Volkov in one of the interviews published in Volkov’s “Balanchine’s Tchaikovsky”: “Tchaikovsky is the greatest Russian composer.” I wonder if, since Tchaikovsky’s music was the principal subject of the work, Balanchine was comparing him to Russian composers of Tchaikovsky’s own generation, as well as somewhat later ones, like those dubbed “The Mighty Five.” Or maybe, by the 1980s, he considered Stravinsky, like himself, to be American, or maybe a citiizen-artist of the world.

This may be a question of semantics, but I think there is a difference between saying Tchaikowsky was the greatest Russian composer, as Balanchine indeed told Volkov in what may be the best book on Balanchine ever written, and calling him Balanchine’s favorite. But I don’t really think it matters, since Mr. B. “collaborated” with both men–literally with Stravinsky, spiritually if you will with Tchaikowsky, to make some truly magnificent ballets.

Deborah,

Thank you so much for mentioning the pianist, Susan Walters, in your See The Music post on Tchaikovsky and PC2. All too often in recent seasons of NYCB, the piano soloists are not even mentioned let alone praised for concertos or ballets set to solo piano scores. After spending countless hours over countless years practicing so very hard not only for the musical integrity of the score, but also to “practice in” the specific rubati and tempi required to fit the dancers needs, it is depressing and disheartening to not even be acknowledged in the reviews. Thank you for your intelligent and generous writing.

Sincerely,

Cameron Grant

I’m astonished to hear that the Prighiera in Mozartiana is being danced with four adult women (presumably the women who later dance the Minuet?) accompanying the ballerina rather than the four girls (who have usually been teenagers, more advanced students). If that’s so, it seems a shocking distortion of Balanchine’s original design, in which the girls are somewhere between acolytes and family–just as the ballet hovers between the sacred and the secular. Thank you for another strong account, Deborah.

Best,

Jay

One more quick thought, on Serenade. The moment where the fated girl lets her hair down I’m sure was designed to be invisible–we can’t be intended to see her release it; rather, the illusion must be that in the hurtle of the corps’s exit, her hair comes down of its own accord as she collapses: its an emblem of her vulnerability & an augury of her impending sacrifice. But in most recent performances I’ve seen, the ballerina struggles with the clip so the hair business becomes its own little distracting agon. Can’t wardrobe devise some quick-release that would do the trick so fate appears to undo her hair, rather than having it look like a conscious fashion decision?

Jay

I was at Saturday afternoon’s performance. The Prighiera was danced (and gloriously) by the principal ballerina (Maria K) with the young girls, just as always. Deborah I am confused therefore–did I miss something?

Thank you, Rhona. Another person sent me a similar query. I saw the performance on Wednesday and am sure I saw the opening as described. My husband agrees with me. But who knows? Having just read Oliver Sacks’s essay on faulty memories in the New York Review of Books, I’m willing to believe I might have been hallucinating. Clearly, more research on my part is called for.

Chiming in very late on the Stravinsky/Tchaikovsky comments, I saw all the programs in the Tchaikovsky Celebration back in January and loved seeing the Balanchine masterpieces. I was especially glad to read what Deborah had to say about Serenade which may well be my favorite ballet. However the highlight of the celebration for me was seeing Tiler Peck and Robert Fairchild in Divertimento from “Le Baiser de la Fee” with music by Stravinsky. I understand Balanchine called this piece “Stravinsky’s Tchaikovskiana” which I assume is the reason the ballet made it into the Tchaikovsky Celebration. Balanchine’s two favorite Russian composers in one piece and in the performance I saw, Tiler Peck was enthralling.

thank you