Dancing Cunningham in Philadelphia, October 26. Front (L to R): Melissa Toogood, John Hinrichs, Emma Desjardins. Rear: Marcie Munnerlyn, Brandon Collwes. Photo: Constance Mensh

“May I have the next dance, Marcel?” “But of course, John!” “Thank you. By the way, Bob and Jap hope to have a chance too. Merce, of course, is already leaping about somewhere.” Dancing around the Bride: Cage, Cunningham, Johns, Rauschenberg and Duchamp, the stunning exhibit at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (through January 21), affirms the close artistic and personal connections among John Cage (1912-1992), Merce Cunningham (1919-2009), Jasper Johns (b. 1930), and Robert Rauschenberg (1925-2008); Cage was Cunningham’s partner and musical advisor to his dance company, Rauschenberg was its resident designer from 1954 to 1964 (and sometimes toured with it), Johns succeeded him at the job (1967 to 1980). Dancing around the Bride, brilliantly curated by Carlos Basualdo, also reveals that these four artists did indeed dance around Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968)—inspired by the obstreperous older artist, friends with him, and, like him, desirous of smudging the boundaries between art and life.

In 1938, Cunningham and Cage met at the Cornish School in Seattle, where the former was a student and the latter an accompanist for dance classes. Cage met Duchamp in 1942, the year Duchamp fled Europe for New York. Cage and Cunningham met Rauschenberg in the summer of 1953, when teaching at Black Mountain College, where the three collaborated on Theater Piece No. 1 (retrospectively considered the first Happening). Johns met Rauschenberg in 1953 and, Cage and Cunningham the following year. Also in 1954, Duchamp, whose work and ideas were to feed into the interests of all four of the younger men, attended Rauschenberg’s show at the Stable Gallery and met the artist. Here and there throughout the Philadelphia show, you find works they made in homage to one another (Duchamp referred to Johns as “the sybil of targets.”)

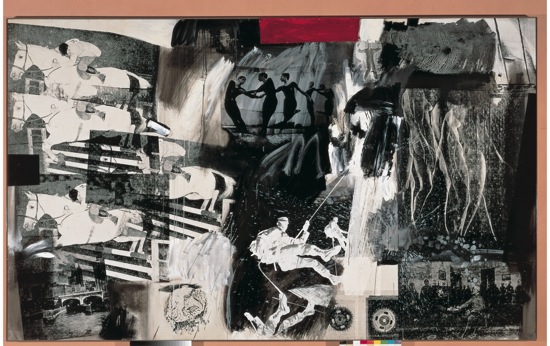

Robert Rauschenberg: Express (1963). ©The Robert Rauschenberg Foundation/Licensed by VAGA, NY, NY

There’s another kind of dance going on in Dancing around the Bride, and I don’t mean just the snippets from Cunningham’s choreography organized by Daniel Squire, which Squire and other former Cunningham dancers perform intermittently on a low white platform in the main exhibit hall. Nor do I refer only to the recorded sounds of dancers’ feet on the miked platform that can be heard when no dancers are around. You, the viewer, may execute mental jetés as you contemplate the bicycle wheels in Rauschenberg’s Tantric Geography, the set for Cunningham’s 1977 dance, Travelogue, and remember Duchamp’s bicycle structure in the museum’s gallery devoted to that artist’s work. Pondering doors—photographed, painted, built—is also good exercise.

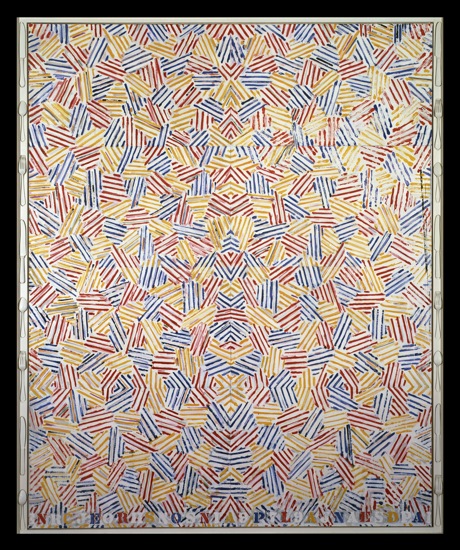

If you sit on the handsome white bleachers watching Squire, Melissa Toogood, and Holly Farmer dance (as I did on January 6), you may recall the photographic images of Steve Paxton, Carolyn Brown, and Judith Dunn that Rauschenberg silk-screened into his 1963 painting Express—a work you gazed at minutes earlier. Their straight-armed gestures and busy, angled parallel paths may resonate for you with Johns’s 1979 painting Dancers on a Plane (the last word referring both to the flat surface and the Cunningham company’s many airplane trips). As the fine, meaty catalogue of the exhibit reveals, these are only a few of the provocatively analogous structures and echoings that jostled together over at least four decades.

Jasper Johns: Dancers on a Plane (1979). ©2012 Jasper Johns/Licensed by VAGA, NY, NY

Then there’s the Yamaha Disklavier that sits near the entrance of the main gallery. Even when its (randomly?) timed recordings of Margaret Leng Tang playing selected Cage works for piano are drowned out— by, for example, the recorded feet on gravel and slowed-down voice in David Behrman’s score for Cunningham’s Walkaround Time and/or Lee Ranaldo (of Sonic Youth) performing assorted Cage works on electric guitar to accompany the live dancing—you can see in the distance the subtle dance of the piano’s keys, lighting up as they’re played by the unseen musician. Ranaldo’s own more flamboyant dance sometimes involves suspending his instrument and swinging it around or scraping a bow over the strings to alter the sound. Here and there in the galleries, as part of the mis-en-scène designed by artist Philip Parreno, small plaques with information light up to indicate what you might be hearing at the time.

Basualdo organized the exhibit around several themes. One is the chance procedures that the artists used to undermine their own habitual practices, as well as the found objects or sounds they sometimes incorporated into their work (Duchamp’s 1913 Erratum Musical preceded Cage’s Music of Changes—his first use of chance—by 38 years). Also explored are their collaborations (direct or indirect) on stage productions. Chess serves as a shared artistic motif (Duchamp was an expert and gave Cage lessons), and also as a symbol of the artists’ exchanges and their playfulness; Johns’s Painted Bronze (Ale Cans) of 1960 stands close to a 1950 replica of Duchamps’ notorious 1917 Fountain (a urinal).

Marcel Duchamp: The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass), 1915-23. Philadelphia Museum of Art

One artwork, Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass), provided the show with its title and most resonant connections. The artist made it between 1916 and 1923, and supervised its installation in the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1954. Accidentally broken in 1926 and mended by Duchamp, its two glass panels, one atop the other, bear the “bride,” a contraption hanging off a high-floating, windowed framework of emptiness, and the nine puny “bachelors” who cluster below, along with other shapes, including a flimsy little bicycle wheel and what vaguely calls to mind a drum set in disarray. Originally, accumulated dust became part of the design. The Large Glass is powerful in its sparseness and its transparency, the latter of which is in no way hindered by the spiderweb of cracks from the early breakage. The Large Glass is placed about six feet from an alcove with a floor-to-ceiling window, so if you stand on one side of it, you see through it to the city below (the museum is on a hill), and if you stand with your back to the window, you see more Duchamp constructions behind his masterwork.

Merce Cunningham’s Walkaround Time (1968), Carolyn Brown, foreground, Set and costumes by Jasper Johns. Photo: ©1972 by James Klosty

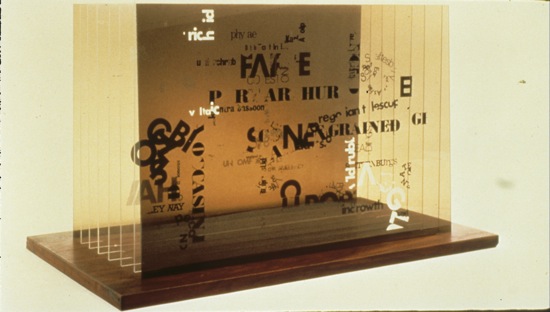

Johns recreated some of The Large Glass’s designs in his set for Cunningham’s 1968 Walkaround Time, transferring Duchamp’s images to five variously sized boxes made of clear plastic. These command the exhibit’s stage when no live performers inhabit it and are raised overhead whenever there’s dancing to look at. Rauschenberg references Duchamp’s piece in his combine Bride’s Folly (1959); the “bride” appears as a waterfall of white paint with a fork glued to it. In 1964, Rauschenberg created Shades, a more transparent homage: a small box of lightly silk-screened panes of glass set on end. Cage (with Calvin Sumsion) designed his beautiful little Plexigram 1 (from the portfolio Not Wanting to Say Anything about Marcel) in 1969, the year after Duchamp’s death. Its eight panels bear printed letters of all sizes, falling down and floating up from words that may once have been complete. (I never knew Cage was such a gifted visual artist. And only a mushroom forager as attuned to nature as he was could have created his lacy 1990 Wild Edible #3, whose pressed materials are kudzu, hibiscus stems, cattails, yellow dock, and more.)

John Cage (with collaborator Calvin Sumsion): Plexigram 1 from Not Wanting to Say Anything about Marcel (1969). ©2012 John Cage Trust

It’s fitting, too, that some relevant works on paper—notes, scores, letters— are filed in a stack of big, shallow, glass-bottomed drawers. You have to ask a guard if you wish one pulled out, but it’s provocative to look down through the layers past corners of this and single lines of that. “Dear Bob. . . .” The rest is a mystery.

Cage once described Rauschenberg’s smooth-surfaced, all-white paintings of the 1950s as “airports for the lights, shadows, and particles.” In the same way, his own 4’33”, in which the pianist sits before the instrument but never touches its keys, could alert listeners’ ears to the world-sounds around them (those listeners, that is, who didn’t object and walk out). I wonder if Parreno was thinking of those works when he placed the white platform and seating in the gallery. The stage catches and records the dancers’ busy footsteps, their pauses, their congruences, their shadows. The fact that they walk onto an island that can be surrounded by watchers, instead of onto a proscenium stage, gives them the purity of marks on a sheet of paper, of particles clustering and separating according to laws we may not understand.

Lee Ranaldo playing, Holly Farmer dancing Cunningham choreography, Jasper John’s set for Walkaround Time suspended, January 2013. Photo: John Vettese

We are provided with lists of the excerpts from Cunningham dances that tell us what will be performed at exactly what moment in time. Spectators come and go in the pauses between their appearances. As always, the dancers do not perform to whatever music or sounds accompany them. While Ranaldo whips his guitar toward chaos, Squire slowly raises one bent leg to the side, angling his body carefully (this is Interscape). The musician is still reading some of Cage’s rigorously timed, often hilarious anecdotes while Farmer balances on one leg in a duet from Fractions, and Squire rushes from one side of her to the other— in order, perhaps, to be at the ready in case she topples.

For all the choreography’s islanded purity, the overall picture is colorful. Through the dancing—both present and transparent—we see people wandering to look at the artwork, children being settled and shushed, friends beckoning friends to come sit by them, rapt watchers. The dancers’ focus never wavers. Squire in Landrover prowls the space with the alert gaze that Cunningham himself always maintained—a watchful animal in an invisible jungle. Toogood, wonderfully precise and complete in her dancing, slices the air in the brief, intricate, physically ebullient solo that begins a segment from Cunningham’s final work, Nearly Ninety (and he was). In a Suite for Five excerpt, she stands, seemingly composed, while her left leg, raised behind her, swings to and fro like a weathervane in a shifting wind.

Andrea Weber and Rashaun Mitchell performing at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, December 21, 2012. At rear: Rauschnberg’s Tantric Geography. Photo: Constance Mensh

As always, Cunningham’s choreography plays unexpected games with time, space, and motion. Actions performed at high speed suddenly pause or are succeeded by completely different, much slower ones. Cause and effect make deceptive appearances and then imply they were only kidding. What causes Farmer to erupt into rapid backward hops or smack a foot against the floor? Only her body knows. When either of the women moves her hips smoothly and speculatively, she’s not out to seduce anyone; she’s checking out the way it feels to edge into the air around her. Images of tenderness, helpfulness, argument, and game-playing surface. You can imagine what you like (including insect mating behavior); the dancing is that down-to-earth, that transparent.

It’s tempting to fantasize the museum at night, with the ghosts of the four geniuses no longer with us in body calling out to one another and setting up some chess pieces from the museum store for a game. Chance and skill pull together once more, and a fine time is had by all.

Even more lovely than usual, if that’s possible. Makes me want to see it again. I’m speaking not of the dancing but of the show itself.

Oh the title was beguiling, thought I was going to read about a Jewish bride circling her groom 7 times, funny enough, but Wham What a SPLENDID celebration you wrote about anyway! It makes me want to hop onto a plane to Philadelphia immediately. Thanks, Judith

FANTASTIC!

Hello Judith! It was wonderful to come across your post here.

“a watchful animal in an invisible jungle…”, just one of many phrases, sentences, paragraphs that sing a song of celebration only Ms. Jowitt could have written. I too want to jump on the next plane to see this show, but as some advertising flack said about some product, this post “is the next best thing to being there.”