Whoever said that dancers can’t talk well in public? These days, shutting up and just dancing is often not in the cards (there are some particulars that movement alone can’t reveal). This struck me when five of the seven performances that I managed to take in during four days of the annual event-crammed conference of the Association of Performing Arts Presenters (APAP) involved speech.

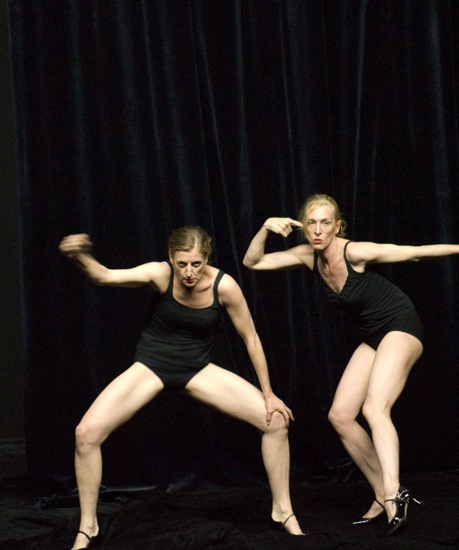

L to R: La Ribot and Mathilde Monnier in their Gustavia. Photo: © Marc Coudrais

Thursday, 1/10, 6PM, Florence Gould Hall at the French Institute/Alliance Française: Gustavia. In this collaborative duet, the noted French choreographer Mathilde Monnier and the Spanish choreographer and visual artist La Ribot talk to us insistently and mostly at the same time—offering varying information, yet backing each other up. These two beautiful women, just past their forties and limber in every way, constitute Gustavia—a woman who’s aware of her seductiveness and her vulnerability, but also affirms her power. A cooled-down burlesque-show ambiance both frames and ironically undercuts their views on life and art. Although they wear black tops, skimpy black trunks or short tights, and either high-heeled shoes or knee-high black boots, they perform on a floor covered with rumpled black fabric (set by Annie Tolleter) and are often dimly lit by Éric Wurtz.

A burlesque queen would never get away with the amount of repetition they offer. Eyeing each other competitively, they grimly assume many ineptly sexy positions, all the while mechanically pulling a pantleg up and down to give us a glimpse of knee; they end up exhausted and disheveled. They begin Gustavia by gasping and whimpering into a standing mic, their distress gradually escalating into full-scale sobbing and eye-mopping. Side by side, staring at us, they offer in rapid-fire French many, many variegated characterizations of a woman (they may be improvising these). Monnier gestures vigorously, La Ribot poses defiantly. In the end, they stand on high stools and offer further random information in English (e.g.“a woman fucks with her neighbor,” a woman is a terrorist,” “God is a woman, a sexual woman”).

Both are marvelous performers, and their well-timed rivalry makes us laugh. However, although the repetitiveness is surely a considered choice, it’s also wearing for the audience. In one episode, La Ribot marches in various directions across the stage with a long, lightweight plank over her shoulder; she doesn’t seem to know or care where she’s going and gets tireder and tireder. Monnier stumbles around, too confused to get out of her colleague’s way. Whap! The plank hits her and she falls. Over and over and over. I want to scream, “Pay attention you dope!” Two aspects of the eponymous Gustavia simultaneously striving and being knocked around in a brutal, endless vaudeville routine: a brilliant idea, infuriating to watch.

Jack Ferver in his Mon Ma Mes. Photo: © Marc Coudrais

Thursday, 1/10, 7:30, upstairs in the small Sky Room: Jack Ferver’s Mon Ma Mes. (FIAF, the presenter, considerately offers a reception with wine and hors d’oeuvres along the way.) Ferver talks a lot. About himself. He’s wittily self-deprecating, savvily informal, engagingly ironic, occasionally poignant. After the gray shades covering the immense slanted windows lift, Ferver walks into the intimate space and tells us that he just got here, that he’s not really prepared. He’ll have the Q & A first, rather than afterward. That process itself is subverted; the audience’s supposed questions have been written in advance on large cards, which an assistant hands out to be read by whichever spectators Ferver designates.

Much of what Ferver says during the performance concerns what is not going to happen. He’s not going to read a story he wrote about a boy enthralled by a fellow track-team member with a very large package (and, no, he is not the boy in the story); instead, he listens while audience member Megan Le Crone of the New York City Ballet sits in his onstage chair and reads it in a clear, mostly unembarrassed voice. Ferver has also decided not to perform a dance that had to do with pushups and being raped; instead, he lounges in the chair and listens while performer and designer Reid Bartelme, summoned from the audience, stands beside him and sings a pause-filled litany of “ah”s in a firm voice—now high now low, the lights glinting off his spectacles.

Ferver is an interesting dancer-choreographer. Clearly expert, yet not refined. Flow isn’t his long suit. In his two solos, he looks as if he’s making decisions—repeating one movement until he’s tired of it, then moving onto something that may be completely different. Perhaps he’ll strike a big, lunge, arms reaching, chest lifted heroically. Perhaps he’ll sashay around in a circle or march or execute a Martha Graham exercise. Some of what he does looks very original, and everything is shrewdly organized.

To demonstrate a possible choreographic process, he opts for another audience member, his friend David, who’s recovering from an injury, to join him for a brief structured improvisation. Up comes David Hallberg of American Ballet Theatre and the Bolshoi Ballet. He is told to keep his palms down, but that he may move his arms wherever he chooses. At each change by Hallberg, Ferver raises his index fingers to touch gently the underside of his recruit’s hands. Hallberg is very tall; Ferver is shortish. It’s a quiet, deliberate, strangely wistful duet.

In the end, Ferver and Bartelme sing together words that are patently not true: “I am the only person here.” The end comes when the gray shades slowly roll down and cover the night sky.

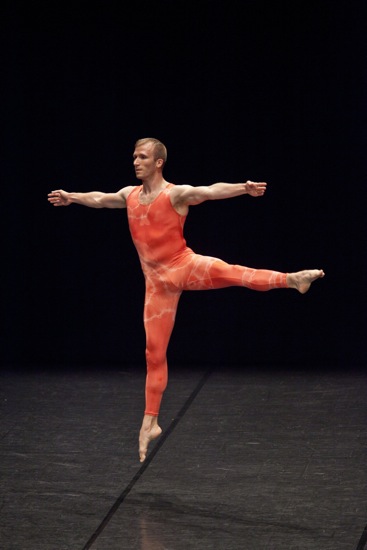

Cédric Andrieux dancing Merce Cunningham in Jérôme Bel’s Cédric Andrieux

Thursday, 1/10, 9 PM, back down in Florence Gould Hall: Jérôme Bel’s Cédric Andrieux. This is one of four solos Bel has made by, with, and about dancers he admires. It is, quite simply, wonderful—both because Andrieux is wonderful and because Bel has shaped his subject’s autobiographical material wonderfully.

In words and movement, Andrieux relives high points of his life and career. When he talks, he stands almost completely still (his left hand performs a minimal dance). His face remains quiet and his voice un-emphatic at all times. This clear, understated quality leaves us free to grasp for ourselves the distress or joy his words unlock. When he holds up and identifies a tie-dyed unitard and a dance belt of the sort he wore onstage during his eight years in Merce Cunningham’s dance company, you sense his discomfort with this attire, although he makes no complaint and goes offstage to put it on.

He tells of his family and of how he, as a boy growing up in Brest, France perceived dance (the show Fame loomed large). Along the way, his narrative sets us up for what he will perform, beginning with the solo, Nuit Fragile, for which he won first prize in his ballet academy’s recital, although his teachers had made him imagine he hadn’t a chance of placing. He runs through the unchanging first minutes of a Cunningham class, mentioning which exercise he hates the most. He demonstrates the laborious process that the aged Cunningham employed to translate his computer-generated movements to a dancer’s body—first educating the feet, then adding the torso’s actions, then those of the arms. We see Andrieux perform a intricate and demanding solo from Biped (1999, his first year in the company) and, later, the one he loved best (with good reason): Cunningham’s own solo in the 1956 Suite for Five. When he tells of having left Cunningham and New York for France and the Lyon Opera Ballet, he transforms himself into a more fluid and impulsive-looking person in an excerpt from Trisha Brown’s Newark.

Throughout Cédric Andrieux, complex passages of dancing are contrasted with stillness. After one bout, Andrieux stands and waits until his breathing steadies before he speaks again. Telling us about a job modeling for an art class, he assumes a pose and holds it until we feel in our own bodies just how painful those minutes could become. To end, he shows us his favorite part in Bel’s the show must go on (restaged for the Lyon company in 2007). The song is the Police’s “I’ll Be Watching You.” And that’s all Andrieux does. Standing at the edge of the stage, he scans the audience. Interested in us. Receiving our gaze without pretension. We can’t take our eyes off him. I may weep.

Gus Solomons jr in Tina Croll and James Cunningham’s The Men Dancers: From the Horse’s Mouth. Photo: Christopher Duggan

Friday, January 11, 8PM, The Theater at the 14th Street Y: The Men Dancers: From the Horse’s Mouth. I know this piece, conceived and directed by Tina Croll and James Cunningham, from the inside out and the outside in. In it, not just one but many performers tell their stories—hilarious, embarrassing, touching, inspiring. This version, unspooling in the wide, shallow space of the Y’s black-box theater, reprises the one that premiered at Jacob’s Pillow this past summer in celebration of that establishment’s 80th anniversary and the all-male company of its founder, Ted Shawn.

Audiences love The Horse’s Mouth. The two-minutes-max stories that the men tell us are embedded in a structured improvisation, so that you always see three others dancing—one in place, one traveling, and the third improvising in ways that may derail the others. Behind them, still photos of major male dancers and film clips of Shawn’s ensemble in action flash onto the wall. The unlikely combinations of people you’d never hope to see onstage together can be intoxicating. Gus Solomons jr, majestic and with a cane, has a little rhythmic exchange with tap artist Jason Samuels Smith. A little later Smith performs his own version of an assemblé, while Steven Melendez of New York Theatre Ballet soars into his more classical one (meanwhile John Mario Sevilla is telling of his Hawaiian childhood experience with the show Oliver!).

Because the stage picture is so vivid, I came to realize the importance of moments of rest or the occasional simple action, like Miguel Anaya gravely walking the boundaries of the space or Pascal Rekoert taking off his jacket and putting it on again. I watch with pleasure John Heginbotham (ex-Mark Morris) build and enlarge a single module of movement through repetition. It’s nice, too (not to say amusing), when Christopher Caines—on hearing Jack Anderson and his partner George Dorris (non-dancing-writer participants) mention Swan Lake— begins to flap his hands delicately; Heginbotham picks up the motif and runs with it. Some guys literally sweep others off their feet. Two tall men as diverse as ex-New York City principal dancer Charles Askegard and Rekoert, formerly of Jennifer Muller/The Works, echoing each other’s moves? Fascinating.

L to R: Jason Samuels Smith (in the dark), Don Redlich, Norton Owen, Miguel Anaya, and Alberto Del Saz. Photo: Whitney Browne

Croll and Cunningham are fine with those who’re not dancing these days; others sub for them. Choreographer Lar Lubovitch talks while behind him the very young self he’s talking about performs his first solo on film. And surprises crop up. In one of the “B” section’s favorite-costumes parade, Jacob’s Pillow archivist Norton Owen vivaciously shakes pompoms in a letterman’s sweater from a 1930s dance by Shawn. Caines, who has told us he studied Celtic languages in college, chants in one of them to accompany 17-year-old Trent Kowalik (one of the original Billy Elliots in London and on Broadway), who began as an Irish step dancer and crosses the stage with erect spine and fine scissoring feet. A crotchety, endearingly shaggy gray monster has spats with a smaller one (Rekoert and the irrepressible Arthur Aviles concealed in costumes by mask-maker and puppeteer Ralph Lee, who participated). In the piece’s opening solo, Chad Hall (later crossing the stage in Marvel comics attire) moves as too few superheroes do and more should.

So many stories, so much experience, such splendidly collegial dancing. All inform one another.

Emily Johnson (L) and Aretha Aoki in Johnson’s Niicugni. Photo: © Chris Cameron

Saturday, January 12, 7:30 PM, The Baryshnikov Arts Center: Emily Johnson/Catalyst. Niicugni is the second part of a projected trilogy by Johnson that began with her Bessie-Award-winning The Thank-You Bar (which I, unfortunately, didn’t see). Johnson’s company is based in Minneapolis, but she grew up in Alaska among the Yu’pik people. Her mission in Niicugni is a large one: to help us “listen to our bodies, histories, impulses and environments,” whether these environments are rural Alaska, with its salmon, bears, foxes, and seals or city streets and what lies beneath them.

The set, which is also a part of Heidi Eckwall’s elegant, atmospheric lighting, consists of 47 lanterns hung at different heights. They were sewn from individual salmon skins by volunteers in five states. The principal performer-collaborators are Johnson herself and Aretha Aoki. Composer-musicians James Everest and Rachel Golub also participate in the action at times, and their spare score evokes chill landscapes and warm gatherings.

Niicugni is one of those pieces in which you sense—and can honor—what its creators are trying to say, yet just because they know their subjects and how the pieces of them fit together doesn’t mean that the audience can always grasp what’s happening. Johnson uses a great deal of language—always poetic, sometimes mythic, sometimes down-to-earth—because storytelling is part of her traditions. Never has the rape of the Alaskan landscape by loggers and builders sounded so terrible and magical as it does in a folk tale told by a tree. Eloquent as it is on the page, Johnson’s story of her unusual blue eyes, inherited perhaps from the very salmon she fishes for and eats is more puzzling than illuminating when she tells it. Other stories allude to curious events that we’re to believe happened today (a duck fell off the roof to avoid a hawk, and is even now wrapped in Aoki’s sweater in the dressing room). At some point, the words that thread beneath, around, and above the actions become hard to focus on and hence distracting—more part of the environment than revelatory.

To remind us how much our lives depend on community, Johnson has minimally-rehearsed volunteers appear from time to time. Sometimes they simply walk on, look around, and go away. Some are mothers carrying infants. Some are toddlers, lured by toy trucks. Adorable, of course, but the whole use of these people is so neutral that their comings and goings don’t register in any depth.

The two compelling women remind us fitfully of animals. When Niicugni begins, they’re lying on their sides, inching toward us by pushing their butts, then their ribcages ahead. A single string is plucked, and other sounds sneak in. Dressed in Angie Vo’s black pants and silver or black tops that are ruched to suggest scales, Johnson and Aoki could be salmon laboriously making their way upstream. Except that they wear flat paper masks of their own faces. At other times, the two creep on all fours or waddle like bears. Once, their faces are obscured by blank white masks, another time by massive, white-feathered owl masks. They also huddle together like little animals, nuzzle each other, whisper secrets we can’t hear. They may speak singly or as one.

Aoki (L) and Johnson turn creaturely. Photo: © Chris Cameron

At some point it becomes clear that Johnson can make movement sequences so original and compelling and elusively creature-like that a stray semi-arabesque looks like an enemy invader. The very fact that the Johnson and Aoki are so interesting to watch further obscures the spoken texts. Johnson in particular confides the words to us with a charming, faintly disturbing manner, as if to reassure us that she is benevolent. That’s not necessary; even the tears she sheds at one point and Aoki’s ferocious snarling grimaces are contained and somehow distanced.

Johnson often shows us something that we’re sure must have depth, but whose surface we can’t get beneath. For instance, she and Aoki connect together and hold up big sheets of white paper (skin?), hiding behind them. Onto these are projected images of their faces at such close range that only half of each visage (brow to neck) fits on the paper and we parse with difficulty the changes of emotion. What does this mean? That the two represent one, their halves making a whole? If that’s all it is, the method of showing it seems both elaborate and redundant. What’s at stake here?

The words are like snowstorms, cold and lovely, that have to be slogged through. Johnson has so much to offer. I’d like to be able to receive it.

Speaking of words, I’ve just written a lot of them. Think I’ll quit.

I hope I win the prize you “might offer” for getting through whole review. Questions:

1. I thought Horse’s mouth was for older established dancers. Does Jason Samuels Smith qualify in that arena. Did I get the definition of Horse’s Mouth wrong?

2. if i’m able to read my handwriting, I liked: “clearly expert, but not refined.”

3. You sound “negatively critical enough to make it back to the Voice. Each piece seems to engage in some form of a knock, though I wish I could have seen them all. did you purposely pick dancers who talk or was that random?

4. Perhaps this would have been the right APAP for my “Rhythm & Schmooze.” I talk and tap and talk and tap.

In answer to Jane Goldberg’s first question, the cast for the first performances of “From the Horse’s Mouth” was composed of mature (and beyond) modern dancers, but quite soon, dancers of all ages working in a variety of styles from hoofing to Bharata Natyam to ballet became the usual mix. This now-famous improvisational structure devised by James Cunningham and Tina Croll can also been adapted for very close-knit groups, such as members of a college faculty and student body. In answer to question 3. I didn’t purposely choose dancers talking as a theme; it just happened that all the pieces I saw over a period of several days featured dancing and talking.

Dear Deborah Jowitt, I am professor of Music Therapy at Wilfrid Laurier University. I am researching the art music of Paul Nordoff. I saw that the Ballet ‘Every Soul is a Circus’ was performed last year (2012) and saw your review. Do you have any contacts for Paul Nordoff the composer. I have written to the Martha Graham company. I also saw a piece by Ada Miranda and wonder if you have a contact for her. With thank,s, Colin

That is a great pic of Gus! Thank you for your review. I wasn’t able to see anything this year 🙁

great to see Don Redlich.

Deborah — I was not able to go to APAP. Your palpable review puts me there.Your words are so descriptive that I can see the performance. Thank you for your wonderful words and your way of seeing. Liz