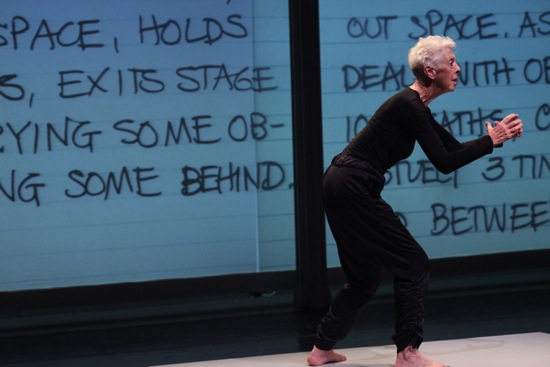

Valda Setterfield duplicating an Eadweard Muybridge photo in David Gordon’s THE MATTER/2012: Art & Archive. Photo: Paula Court

David Gordon is the King of Repetition, and I don’t want to hear any back talk. He manages dance material like someone holding an object up to direct sun, then to a candle flame, setting it against different backgrounds, turning it sideways. “Look at it now. Now look again.” He’s also a master re-arranger—juxtaposing past to present, rehearsal to performance, new to old, life to art.

Gordon was one of the original members of Judson Dance Theater, so it’s fitting that his THE MATTER/2012 Art & Archive be shown as part of Danspace Project’s ongoing Platform 2012: Judson Now, which honors the 50th anniversary of that gloriously, crazily, brainily obstreperous bunch of artists, who put on their first show at Judson Church in 1962. The performances at St, Mark’s Church constitute a highly selective retrospective of Gordon’s own early career, focusing on his solo Mannequin (1962), three versions of The Matter (1971, 1972, 1979), Chair (1975), and The Photographer (1983). He has woven together in ingeniously theatrical ways photographs, film and video clips, live-feed video, props, and text that scrolls continuously along the base of St. Mark’s Church’s balcony.

Entering the church is like walking into an installation, except that we’re confined to seats along one of the side walls. Here’s what we see bathed in Jennifer Tipton’s splendid lighting. Blue metal folding chairs, neatly set in place within taped lines; a small central platform; five medium-sized portable screens, each bearing six panels of archival black-and-white photographs; one-largish, photograph-studded cube; two panels each bearing a looped video—an overhead shot of three people (one of them Gordon’s son, Ain) moving dishes around on a table, another of the 1972 The Matter performance.

Three hanging panels at the back initially show (many times, in several poses) ten people important in Gordon’s history (including three who performed in The Matter in the 1970s). Also included: Laurie Uprichard, former director of Danspace; Brenda Way, head of the dance department at Oberlin College when The Matter premiered there; lighting designer Philip Sandstrom; Bill T. Jones; and Elizabeth Streb. This stylish and handsome museum also includes music (I can identify the voice of David Vaughan, as one of the many heard singing the 1910 hit “Every Little Movement Has a Meaning All Its Own”).

The poses of these “guests” evoke Eadweard Muybridge, the late 19th-century photographer whose stop-action images of athletes, dancers, horses, etc. implied—like a film strip—the motion between positions. Muybridge was the subject of The Photographer, an opera by Philip Glass that Gordon choreographed for its performances on BAM’s 1983 Next Wave season. But Muybridge’s images were also the guiding structure behind a solo, One Part of the Matter, that Gordon made with his wife, Valda Setterfield. It is the poses from that solo that the marvelous Setterfield carefully assumes (appropriate facial expressions and all) on the platform in the middle of St. Mark’s. At the same time, we hear Gordon kibitzing and Setterfield arguing (and both of them laughing) during an early rehearsal of the solo, while the text of their dialogue runs along above the action.

THE MATTER/2012 Art & Archive begins and ends with a procession. I choke up during both. The first is an iteration of a parade that Gordon presented on the Dance in America program, Beyond the Mainstream. The accompaniment is Ludwig Minkus’s repetitive melody for Act III of Petipa’s 1877 La Bayadère. Only instead of a ghostly corps de ballet of 32 women repeating the same four-measure phrase over and over, as they fill the stage with a zig-zag pattern, Gordon’s 32 people simply walk.

Setterfield leads the long line of seven featured dancers and 24 students from the Department of Drama at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts. Dressed in assorted, everyday black clothes, they walk at a measured, leisurely pace; some have their hands in their pockets or hold them clasped behind them. Tall, short, skinny, voluptuous, glamorous, plain, young, mature, male, female, they pass gravely by. But shortly after they turn the first corner to start the zig-zag, they appear to approach a concealed camera; the screens across the back fill with close-up, black-and-white images of their faces. Because of the camera’s angle (Madeline Hollander is the media artist) and the turns of the procession, we see faces and half faces and quarter faces and slices of faces behind the leader of the moment. It’s like watching humanity on the march in some apocalyptic movie.

Archival images and scrawled notes link present and past. Scott Cunningham and Karen Graham (longtime Gordon performers) talk and practice movements, and they, plus Andrew Champlin and Jeremy Pheiffer, work in pairs while films and stills of Setterfield and Gordon rehearsing a duet are projected on the rear sheet. It’s that unforgettable early duet in which they take turns slipping out of an embrace and returning to it, while the partner left behind maintains the position, arms enfolding air. How young and beautiful and tender they look in one projection (and only slightly older in the other)!

Chair Dance. Identifiable (L to R): Jeremy Pfeiffer, David Irwin, and Andrew Champlin, and Lauren Kelly Ferguson. Photo: Paula Court

In The Matter/2012: Art & Archive, life and art intersect too. In his early Judson work, Mannequin Dance, Gordon, wearing a bloody lab coat—holding out his hands and wiggling his fingers—slowly revolved while descending into a squat and singing (in a Yiddish accent) “Get Married, Shirley, Get Married” and another song. At St. Mark’s, his 1962 image backs the young 2012 performers doing the minimal dance and singing under their breaths in their own timing (the church resonates like a discreet beehive). The scrolling text reminds us that in 1962 Gordon was dealing with a recent experience—counteracting a case of body lice while slowly lowering himself into a bathtub of disinfectant; the words also revealed that he’d had to race to perform Mannequin Dance at Judson from the hospital where his son had just been born.

The action onstage accumulates, dissolves, and cross-fades with a filmic fluency. The past embeds itself in new circumstances and acclimates. Chair Dance, originally a duet for Gordon and Setterfield, is performed in a unison line by Cunningham, Graham, Leslie Cuyjet, and Lauren Kelly Ferguson, along with David Irwin, Pheiffer, and Champlin—with each first person eventually running to the end and the second one advancing to the lead. Toward the end of the 50-minute retrospective, more and more students, facing us, join for a speeded-up version of the maneuvers—sitting in various ways, tipping the chair, crawling through its openings, lying beneath it. And the final snaking parade consists of Muybridge poses on the move, while Philip Glass’s music for The Photographer swells and exalts. This procession ends with the performers arranging themselves in tiers on the altar steps. By the time Setterfield, the star, has slipped into a place kept for her in the ranks, the cast members resemble a choir about to burst into a resounding hymn. But because this is a postmodernist’s jubilee, they don’t. They take a curtain call.

A bounty of imagination, wit, skill, and, yes, love went into those five decades of work. And into this beautifully constructed living album that reconsiders them.

Reading the above is the next best thing to being there, which I would have loved to have been. I saw the 1979 iteration of Matter in the service of the first piece I wrote for Dance Magazine, remember it vividly. Thanks, as usual, Deborah, for writing that puts me in the audience with you.

This opening paragraph reminds me of the difference between recycling when you’re out of material and reusing because you’ve made something worth keeping around. I came to David Gordon late, but also just at the right time for The Private Lives of Dancers. I loved the way that the pieces shifted, like one of those thumb puzzles where you have to keep moving it around until it all falls into place. I’m looking forward to seeing how this artist mines his past work for new relevance and irreverence, and am glad to read this long-view on his retrospective.

I constantly spent my half an hour to read this webpage’s articles or reviews everyday along with a cup of coffee.